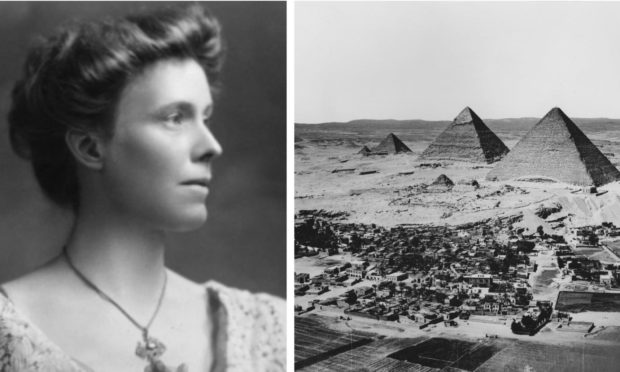

There has never been any shortage of pioneering women in the north of Scotland who have been prepared to embrace the wider world and boldly go where their predecessors feared to tread.

In Nora Griffith’s case, the journey steered her from a privileged upbringing in rural Aberdeenshire to those vast imposing wonders in Egypt: the Pyramids.

And although the very notion of women entering the archaeological realm was airily dismissed by many people in the 19th and early 20th century, she simply ignored any prejudices, flung herself into her vocation with a genuine sense of intelligence and intuition, and established herself as a trailblazer in the field of Egyptology.

Born in 1870, Nora Christina Cobban Macdonald was a member of one of those sprawling Scottish families who seemed to embrace every aspect of life in Victorian times.

The daughter of Surgeon-Major James Macdonald, from Aberdeen, she was also the sister of Sir James Ronald Leslie Macdonald, who stamped his imprint on the world as an explorer, a cartographer and a British Army engineer.

Her talents flowered at an early age

Yet, if there occasionally seemed to be no end to his talents, his sibling was equally versatile; an inquisitive young woman who soon demonstrated her prowess as a skilled photographer, illustrator and curator with an expertise in ancient and modern languages. At a time when so many young ladies of her generation were expected to stay at home and wait to find a suitable husband, she laughed at the idea of domesticity.

Instead, she was fascinated with Egypt and archaeology and assiduously highlighted her gifts while working as a conservator in King’s College at Aberdeen University, where she lived up to the adage that genius is an infinite capacity for taking pains.

Day after day, week after week, she immersed herself in her specialist subjects and her work ethic soon earned her a burgeoning reputation in a male-dominated milieu.

Love blossomed between Nora and Francis

There was nothing prosaic about her affection and knowledge of Egypt, nor her sense of wonder when she visited the country and gazed upon the Pyramids she had only previously read about in books and journals.

Eventually, she delved deeper into ancient history and became attached, both in the lecture theatre and the wider world with the renowned British Egyptologist, Francis Llewellyn Griffith at Oxford University.

It was a partnership which achieved so much before and after the two were married in 1909 and Nora meticulously assisted her husband in his studies and excavations for the next 20-plus years in Egypt and Nubia from 1910-13 and in 1923, 1929 and 1930.

These assignments were not without their challenges. Even in academic circles, women were usually expected to stick to secretarial or library duties and not even consider taking on the chaps at their own game.

That helped explain why, although she published several well-regarded articles in a number of scholarly journals, she is frequently overlooked in the annals of Egyptology.

Abeer Eladany speaks about Nora in glowing terms

Abeer Eladany is a museum curator and an Egyptian archaeologist at Aberdeen University, who recently sparked international headlines with her discovery of a 5,000-year-old piece of wood in a cigar box in the Granite City.

Engineer Waynman Dixon originally unearthed the artefact among a collection of items inside the pyramid’s Queens Chamber in 1872.

The piece of cedar, which it is believed may have been used during the monument’s construction, was originally donated to the university in 1946, but had gone missing for nearly 75 years until it was found by Ms Eladany in December 2020.

Ands she spoke warmly about the contribution made to archaeology by Nora.

Ms Eladany said: “Nora Macdonald – as she is known here in the university museum circle – was a pioneering Egyptologist who joined the field of Egyptian Archaeology at a time when it was dominated by male archaeologists (some might argue it still is).

“Her role as a conservator at the Archaeological Museum at King’s around 1896 is remarkable and inspiring.

“Nora was one of three female scholars who took charge of the cataloguing, classifying and display of the newly-acquired extensive collection of Ancient Egyptian artefacts donated by Dr Grant Bey of Cairo and opened to the public in 1899.

“She inscribed the labels for the new display as well as cataloguing the objects [and there were around 2,000 such items].

“I have spent most of lockdown transcribing her handwritten catalogue which has given me an insight into her vast knowledge of ancient Egyptian history, art and language.

“The catalogue contains accurate illustrations of objects from the collection as well as sketches of ancient deities that highlight her understanding of the Egyptian art canons.

“Her work and dedication have always inspired me and, because I work with the same collection, I feel honoured that I am following in the footsteps of somebody who was an outstanding and a pioneering scholar.”

Nora maintained her husband’s work after his death

Tragedy struck Nora in 1934 when her husband died at the age of 71, but, true to type, she refused to wallow in grief and made it her mission to complete the copious amount of research material which they had collaborated on in the previous three decades.

It was her who prepared his unfinished work for publication including his two-volume magnum opus, Demotic Graffiti in the Dodecaschoenus, which was augmented with 70 illustrations in addition to photographs taken by herself.

Then, even in her 60s, she organised and funded a series of further excavations at Firka and Kawa in the Sudan and financially supported the Egypt Exploration Society.

A lifelong passion and an eternal flame

Nothing was too much trouble for this formidable character who packed further adventures and academic studies into the last few years of her life.

She added to and expanded the already large Egyptological library which had been collected by her husband and herself and which was later donated to Oxford University and added her own personal fortune to that of her late husband for the building and endowment of the Griffith Institute amid the gleaming spires.

However, her thirst for fresh challenges ended abruptly when she died of peritonitis after an appendectomy in 1937 at the age of just 66 and was buried with her husband in the city’s Holywell Cemetery.

It was a severe shock to her colleagues and her family who had been proud of the many accomplishments to which she had committed herself.

Thankfully, her endeavours have never been forgotten in her native north-east Scotland and Aberdeen City Council approved the erection of a special blue plaque to honour her life as “a noted Egyptologist”, which was unveiled in November 2018.

It’s located in the Kings College Quad.

Not far from where she did so much groundbreaking work and where Ms Eladany is following in her esteemed footsteps.