An exhibition of computer-generated art in Dundee features one program that will have generated around 36 million ‘paintings’ by the time it ends next month. Ursula Pool talks to the exhibition’s curator, Donna Holford-Lovell.

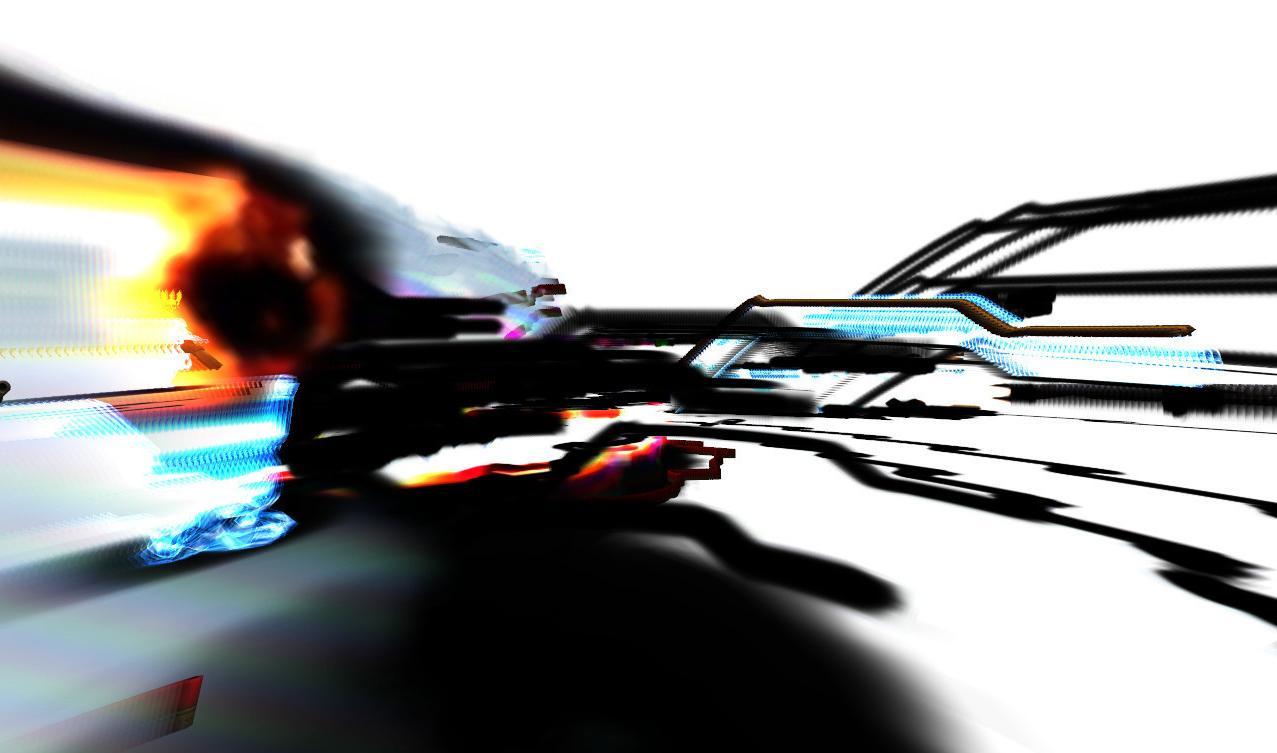

At first glance, Julian Oliver’s artworks look like abstract graphic patterns. However, closer inspection reveals the occasional element that hints something deeper and perhaps darker may be at play — it’s possible to make out a gun in one, for example.

The computer-generated artworks aren’t quite as abstract as they might first appear, explains exhibition curator Donna Holford-Lovell. They are effectively screenshots from a computer game designed specifically to produce paintings as a by-product of the game.

“This piece of software that Julian Oliver has generated is based on a games engine that was used for the game Quake, which is a first person shoot-’em-up game. Quake has a huge underground following, and an earlier version of it was reprogrammed to become an open source piece of software so it could be released openly with no copyright issues and anybody could freely use it or manipulate it.

“Julian took this and decided to use it, not from a games interest, but as an artistic tool. So he’s stripped down the game, he’s taken away some of the vector graphics so it doesn’t look like a traditional gaming environment, although it still functions as such. But the environment then generates this imagery.”

The program will run continuously for the duration of the exhibition and its output is being projected on to a screen for visitors to watch. Images displayed on the gallery walls are prints made from screenshots from a previous iteration of the game, and are clearly similar, in both style and content, to the slow-motion drama unfolding on the projector screen.

“To create these images, Julian has let the game play — he purposely runs it to let it paint. He then stops it at a point he chooses, and, in essence, prints that image out.”

“The system is constantly generating these kinds of images. It’s a pre-programmed gaming environment where there are four robots running around shooting at each other. But because Julian has changed the way the programme works and changed the graphics, every movement that’s made by these robots is kind of dragging the graphics behind it and changing the formation of the graphics. And that’s what generates the images.”

It amounts to painting with pixels, Donna says. Although on one level the robots are trying to kill each other, on another level they are creating art.

“He sees the robots as if they’re painting something within this gaming environment — you can see the marks that they’re leaving as they move around in it.”ManipulateIt is possible for users to manipulate the parameters to alter the progression of the game as the robots battle for supremacy in their virtual universe.

“Through the interface that’s connected to it you can change how the graphics are painted. You can turn it into solid graphics or break it down into the frames of the graphics, for example. Once you get into the menu, you can add another robot to it, or take a robot out; you can change the way they run about and that kind of thing. But they’re constantly running about shooting at each other as if somebody was playing the actual game Quake. Every now and again you’ll see one of them falling over, or a rocket going off.”

Julian Oliver was born in New Zealand and is now based in Berlin. His background is in open source programming, and the crossover of programming and art.

“In essence, he manipulates programming and software to produce art output, or turns it into something that’s slightly aesthetically accessible. For this particular project he’s been working on the software for a few years now, but there’s never been an exhibition of the output, and he’s never released the piece of software. It’s not yet readily available.”

So is he an artist or a computer programmer?

“I think he’s a bit of both,” says Donna. “He’s one of those rare individuals who can move between both.Aesthetic”My interest with it, particularly for Abertay, was from the programming point of view. Programmers usually tend to work on a functional output or a commercial output, whereas Julian’s doing it purely for an aesthetic output.

“His work is very playful. There’s a certain kind of sensibility to it. Yet there’s always that sense of something virtual, that doesn’t really exist, out of all this technology that’s usually quite rigid. It’s taking things back to a kind of expressionist level.

“Julian actually equates the work to expressionist painting. He sees the system as painting. It’s just using a different medium from paint — he doesn’t see any difference. I think eventually he would like it to be a system that you do use for painting, so it maybe moves away from the randomness and becomes more of a tool to paint with.”

And for anyone who’d like to try painting with pixels for themselves, by the end of the show there will be free CDs of Julian’s program available from the gallery.

“People will be able to take it home and play with it, and even rewrite it if they want to — it will be the actual piece of software we have here, and you will be able take away and run the game on your own computer.”Back Buffer: New Arena Paintings, by Julian Oliver, is at the Hannah Maclure Centre, University of Abertay Dundee, 1-3 Bell Street, Dundee DD1 1HP. The exhibition runs until April 30. Admission is free. To register interest in receiving a CD containing the automatic painting program, email exhibitions@abertay.ac.uk with your name and address or visit the gallery.