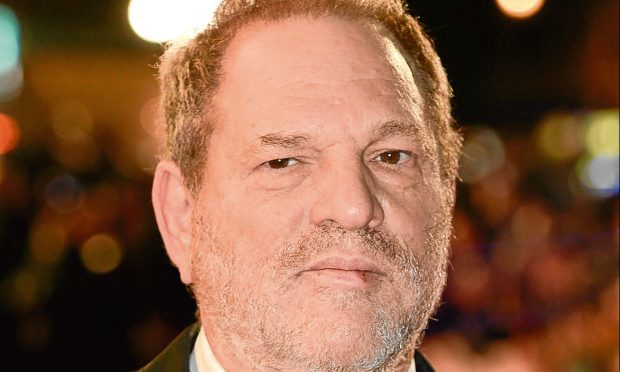

Now the fatberg of Harvey Weinstein has been removed from the sewer, other lumps of congealed oil are flowing into sight.

We can marvel at the details but who has the energy to pretend it’s a revelation. Male boorishness against women, to the point of abuse and rape, is so common it is no surprise.

There is a drama involved with the downfall of a figure like Weinstein, and the fact that his victims were pretty actors, which doesn’t attach to, say, the boss of a double glazing company, but let’s not create a hierarchy of perversion based on glamour.

Who hasn’t got a story about a male boss or elder who behaved inappropriately towards a woman? Men are pervy to the point of criminality at all levels of society.

Let’s purge politics and showbiz of abusers, but don’t stop there. This isn’t a story about Hollywood or Holyrood, it’s about all men, in all professions and trades.

As the issue of male abuse of power to gain sex and harass women escalates, we are in danger of losing some of the key details.

It is right that Holyrood should set up a helpline for people to report instances of abuse, but why hasn’t the Royal Bank of Scotland done something similar? Only a fortnight ago, the banker Jayne-Anne Gadhia told MPs female staff were expected to sleep with a boss.

RBS is an economy-wrecking example of when macho culture goes wrong – there should be as thorough an examination of it as there is of parliament. The same goes for the BBC. No sooner was it revealed that the Beeb operated institutional sexism through pay, than some male staff were being identified as sex pests.

Doesn’t the Beeb need a helpline, too, a means by which past crimes and current perversion can be reported? In other words, we need a better mechanism for women, in all workplaces, to report abuse.

Nor should we allow the volume of complaints to diminish our anger or the scale of punishment.

Sexual harassment has been illegal since the Sex Discrimination Act of 1975. That is more than 40 years ago – and yet, much like the Equal Pay Act of 1970, is something which can still be regarded as debatable or a grey area of policy.

There is no vagueness – women should be treated, and paid, just as men. Nor is there any real doubt in our minds that they are not – hence UK cabinet ministers can still be caught out by creepy sex texts to women 30 years their junior.

Thus this is not a revelation for society, an outrage which might lead to new measures, but a well-known crime as described by existing law.

When thieves are caught, people do not say: “Well, I suppose we all knew, but it just didn’t feel right to say anything.” When cars crash, the police don’t look the other way, afraid to upset the sensibility of the community.

Yet it takes a sex monster in Weinstein to finally make people sit up to the criminality of sex abuse.

On that level, this isn’t a political matter, but a legal and social one. The social element is that, clearly, we have to set up better means of reporting sex abuse and abuse of power. The legal one is: we have to stop faffing around and fire or prosecute sex pests.

The first outcome from the Weinstein sex scandal must be a final call on all male oppression and abuse of women. The story also tells us something about our politics.

For all the cheering about strong women coming to the fore and having a woman as First Minister, there are clearly some issues which female politicians find hard to handle.

Nicola Sturgeon rightly tells us this is a male issue and that it should be stopped, but it took the exposure of a monstrous, and well-known, man to get the matter raised.

Why didn’t Nicola Sturgeon, or any other successful female politicians, raise the matter as a core piece of their manifesto?

Why, for that matter, didn’t Ms Sturgeon hold back money from those local councils which continued to pay women less than men, and block in the courts any effort to have this historic injustice reversed?

My impression is that these weren’t put front and centre by female political leaders for fear of looking “anti-men” or too “strident”.

The calculation by successful female politicians is that they need to project competence and authority on classic political matters – the economy, security – and to avoid appearing overly feminist.

This maybe the second great win from the Weinstein story – that woman in power can be unashamedly pro-women.

There are two great inequalities tolerated in our society: poverty and the oppression of women.

Perhaps we can finally end the latter by genuine intolerance of male sexual harassment and by women championing true equality with the vigour and passion the matter needs.

Time to move on, to make the law absolutely clear, and the meaning of equality absolute.