Most writers will admit that heartbreak is a great motivator for getting words on the page.

But for Broughty Ferry author Andrew Scott, one youthful breakup launched a lifelong fascination which turned into a whole novel franchise.

The Aberdeen-born writer, who won the Dundee International Book prize in 2000 for his first novel Tumulus, is the man behind the ‘Willie Morton’ series, which follows freelance investigative journalist Morton into the murky world of Scottish political conspiracy and espionage.

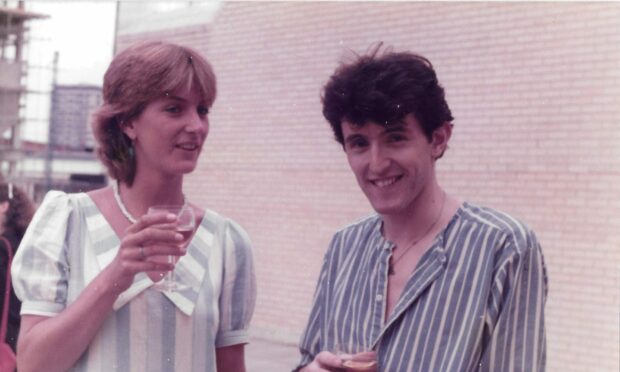

And though the stories weren’t written until much later, they started in 1982, in London – with a girl named Cathy.

“In November 1982, I lost my girlfriend to MI6,” Scott says bluntly.

“We’d been seeing each other for three months even although Cathy already had another boyfriend, John. I saw her during the week and she was with him at weekends. It was intense.”

Drawing a parallel with the “deceit and duplicity” of modern relationships, Scott reveals that though he knew about John, John didn’t know about him. Already, Cathy was proving to be good at keeping secrets.

“He worked on the fish counter at Harrods,” recalls the Ferry-based author.

“Once, I went in just to see what he looked like. The swine was good-looking. But she wouldn’t drop him or me, so it was a very-stressful three-way thing.”

‘She had been instructed to make a clean break’

However, Scott would soon find out that his sweetheart’s other sweetheart was the least of his worries, when Cathy “dropped a bombshell”.

“Apparently, a woman had phoned her at work right out of the blue,” he explains.

“She’d said: ‘Call me Auntie Audrey. You ticked a box four years ago when you left school saying you wanted to work for the Foreign Office. Yes? Still interested in working abroad? Let’s meet and talk about it.’

“By the time Cathy told me this, they’d already had five meetings in a wine bar and she was all set to quit her job and move to Geneva.”

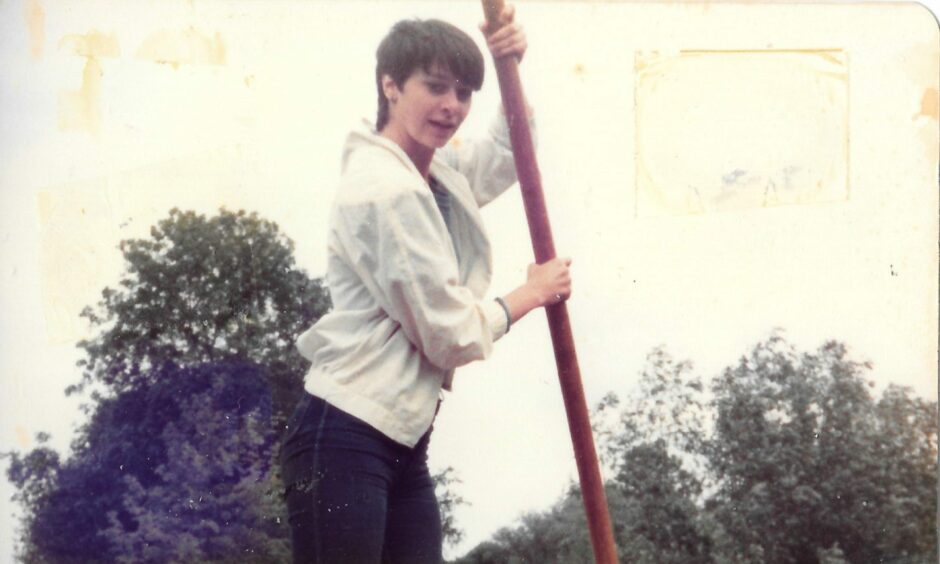

Despite this turn of events, Scott continued the relationship with Cathy, and saw as her ‘handler’ – “another source of anxiety, he was male and I suspected she fancied him” – helped her through many failed attempts to secure a job as a secretary in the United Nations building.

“The intention was for her to pick up titbits of information from Russians and East Europeans,” Scott explains.

“Of course, I worried what that might involve. Was she supposed to befriend these people, or worse? How far would she be expected to go to get information? You could imagine my anxieties.

“Anyway, she was living at UK tax-payers’ expense.”

After an ill-conceived night out with Cathy and her swish Swiss pals, where it was clear to Scott that “living the high life in Geneva had changed her for the worse”, he called it quits with her.

“By the end of that week, I hated her,” he says. “Later, I realised that she had been instructed to make a clean break with her past, including me.”

Ordinary people make the best spies

Two years later, Scott bumped into Cathy in Paddington, and though she’d moved back to the UK for good, he “had no idea” if she was still a spook or not.

“It took me a while to get over Cathy,” he admits. “But the point is, this offers a telling insight into how MI6 and other branches of the SIS work by co-opting or corrupting very ordinary people.”

Combined with his own stints in Westminster and Holyrood as a press officer, Scott’s interest in the way intelligence agencies recruit people gave way to a wider discussion about devolution and the lack of information around devolved intelligence in Scotland.

“It is an unanswered question, perhaps even an unasked question, as to how the remit of MI5’s Department F (political subversives in the UK) has altered subsequent to devolution and especially now that the SNP has representation on the Intelligence Security Committee,” observes Scott.

“In fact, the way in which the real work of the SIS agencies is viewed is largely through fiction. There’s a useful background of what is known or believed, mostly based on spycraft memoirs of former members of the SIS agencies.

“But this leaves a lot of useful leeway for writers to speculate in fiction.”

Scotland is ‘perfect’ location for espionage fiction

And so Willie Morton was born, with each of Scott’s novels putting the fictional journalist into “desperate conflict with spooks of one sort or another against the backdrop of constitutional debate”.

The most recent instalment, Sovereign Cause, draws parallels between the Scottish and Catalonian independence movements and “makes the point that the secret state never forgets a betrayal”.

Beyond the old author’s adage of “write what you know”, Scott’s decision to set his novels in Scotland is definitely intentional.

“Scotland in the 21st century is, for me, the perfect location for spy novels, because of the ambiguity of its present situation,” he explains.

“We’re devolved but not independent, tied to Europe but no longer formally part of it, anti-nuclear in opinion but hosting a mighty nuclear arsenal. Divided in ourselves and uncertain of our future role and nature.

“Perfect, in other words, for espionage fiction that may cast new light on the transformation of the ordinary into the extraordinary – from bystanders and even girlfriends to volunteers and spooks.”

Sovereign Cause by Andrew Scott, RRP £8.99, published by TWA Corbies Publishing, is out now. Scott will be reading from, and talking about Sovereign Cause at St Mary’s Church in Broughty Ferry on Friday September 29.