Sir Alex Ferguson and sentimentality tend to go together like Boris Johnson and a comb, but there was something heart-rending about the trailer for the former manager’s new film Never Give In.

The documentary, which chronicles the Scot’s myriad triumphs in football, and also illustrates how close he came to death after suffering a brain haemmorhage two years ago, will hit cinemas at the end of May and, as you might expect, most of the focus will be on his achievements at Manchester United, whom he transformed from a club living on past glories to the powerhouses of the English Premiership, during his 26 years as manager.

There is certainly no denying the momentous impact which he made on Old Trafford affairs for more than quarter of a century: after all, the Red Devils amassed a staggering 38 trophies, including 13 championship titles, a brace of Champions League honours and the FA Cup on five occasions.

Yet, personally, I think that Ferguson’s greatest accomplishments came at the start of his managerial career when he arrived in the Granite City in the late 1970s and was the catalyst for Aberdeen FC embarking on a giddy whirl of unprecedented feats, jousting with giants and becoming European behemoths in a fashion which, let’s face it, will never be repeated.

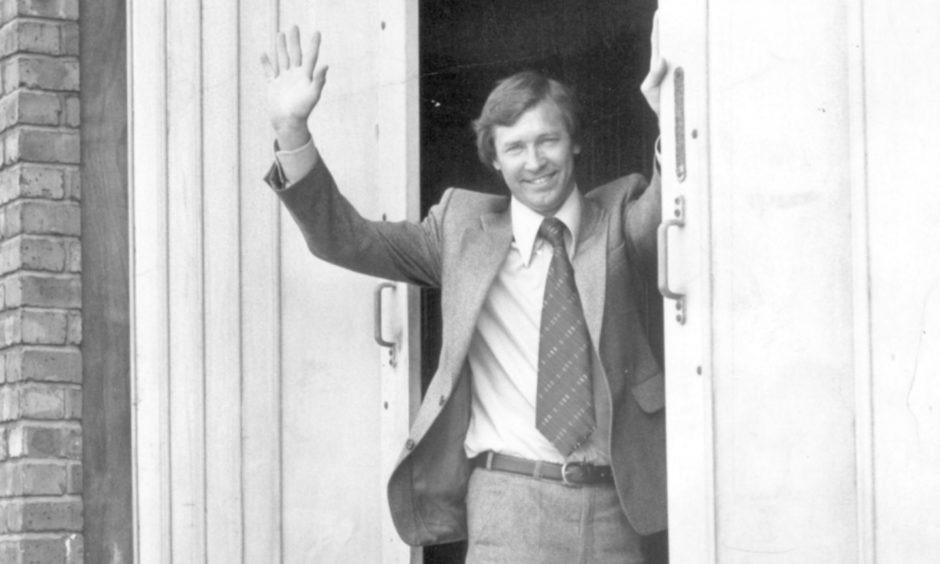

Looking back now, it will probably be difficult for anybody under 40 to realise the sheer force of nature which Ferguson was in those early days at Pittodrie. When he walked in the door, he was still in his 30s, a man consumed by football, but who faced a huge challenge in orchestrating his club’s development from a modest provincial team to a star-studded elite.

It helped, of course, that he was surrounded by redoubtable characters such as Dick Donald and Chris Anderson, working assiduously behind the scenes, and Ferguson was blessed with the nucleus of a very good squad, which he had inherited from the likes of Eddie Turnbull and Ally MacLeod.

But just consider this. Prior to his appointment, the Dons had won the Scottish championship only once – under Dave Halliday in 1955 – and they were in a situation where the best they could hope for was intermittent success in domestic cup competition. They were miles behind the Old Firm, with no ambitions of meeting, let alone beating the best in Europe.

And yet, Ferguson dragged them out of that lowly station and upwards into the stratosphere where they trumped the maestros of Real Madrid in a European final in the space of less than five years. The fire in his belly could be ferocious and he refused to accept second best.

It was his way or there’s the exit, pal. Anybody who crossed him lived to regret it, often in a flurry of what is euphemistically described as “industrial language”. His tirades against alcohol, laziness, complacency, bad time-keeping….anything which might diminish his team’s quality, was unrelenting and intimidating. There was one instance where a stray balloon burst a few feet behind him in the dug-out and Ferguson furiously swore at it.

He appreciated, right from the outset, that Aberdeen couldn’t afford to wallow in anything resembling a comfort zone. As a gnarled Glaswegian with an acute knowledge of the Old Firm, he both respected many of the traditions of Rangers and Celtic and loathed the religious sectarianism which he had witnessed for himself while playing at Ibrox.

Ferguson was only interested in people who could dare to imagine what had previously been a pipe dream; that Aberdeen would not merely gain parity with the Old Firm, but transcend them, leave them behind and aim for bigger scalps when the likes of Liverpool and Bayern Munich came calling.

Some may respond that he was fortunate to inherit the Dons’ job when Celtic were struggling to replicate their success of the Jock Stein era, while Rangers were slipping into mediocrity under John Greig. But that is to ignore the visceral sense of pride, passion, positivity and attacking philosophy which Ferguson brought to the dressing room during his tenure.

It was there almost from the outset: the fearless resolve to make Pittodrie a fortress, allied to the mantra, which was stamped into such talismanic players as Willie Miller, Alex McLeish, Gordon Strachan, John Hewitt, Dougie Bell, Doug Rougvie and Neale Cooper, that opponents should worry about them, rather than the other way around.

So too, the fire-and-brimstone Govan preacher spread the message that Glasgow, for so long a graveyard for the Dons, was just another city with two clubs whose players were only human and whose supporters were notoriously prone to losing patience and jeering their own when the going got tough.

If Ferguson had been a mild-mannered master tactician, he wouldn’t have commanded such respect and reverence, nor been able to rule with such an iron fist. But equally, if he had simply been a cantankerous bully, he would never have orchestrated such sustained momentum among both his squad and the fans who flocked to the Beach End and other parts of Pittodrie.

Instead, his quest for perfectionism and new prizes meant he was as hard on himself as anybody else and the results speak for themselves. On and off the pitch, even on holiday, this man’s competitiveness was unstinting. During quizzes to and from matches, he would reel off the cast of 12 Angry Men and The Magnificent Seven and pluck other pieces of knowledge out of the air.

It was in his genes, instilled in his DNA, that Aberdeen had to be better, fitter, more clinical and, ultimately, more professional, than their rivals. We’ve heard all about Alfredo Di Stefano’s praise for the Pittodrie organisation after the European Cup Winners Cup final in Gothenburg – “Aberdeen have what money can’t buy: a soul, a team spirit built in a family tradition” – but this family was much closer to The Sopranos than The Waltons.

And what riches this implacable clan gathered. In just eight years, there were three league titles, four Scottish Cups, a League Cup and two European baubles: the CWC on that legendary May night in Sweden, followed by fresh success against Hamburg in the final of the European Super Cup just a few days before Christmas in 1983.

None of this happened by accident; all of it was the cumulation of Ferguson’s synergy with some of the biggest figures in the history of the Scottish game. In the process, and even as oil wealth started transforming Aberdeen and the wider north-east, there was a seismic shift in the football landscape even it simply proved to be a transient phenomenon.

Bob Crampsey, the late TV pundit (and a highly intelligent scholarly figure) once talked to me about the ‘magic trick’ which Ferguson had pulled off in such a short time among the Dons. As he said: “Alex can be brusque, he can shout and scream at his players and put the fear of God into them.

“But he is a very bright man, who also has a lot of affection and concern for these young lads. He wants them to avoid the pitfalls which he saw befalling other folk of their age when he was growing up in Govan.

“I have seen him venting his wrath at some people, then, a few minutes later, he will be chatting to them with a smile on their face and the air cleared or taking the trouble to phone them the next morning and say sorry if he had crossed the line.

“When it comes to winning football matches, he’s a very hard man. But there’s a lot more to his story than that.”

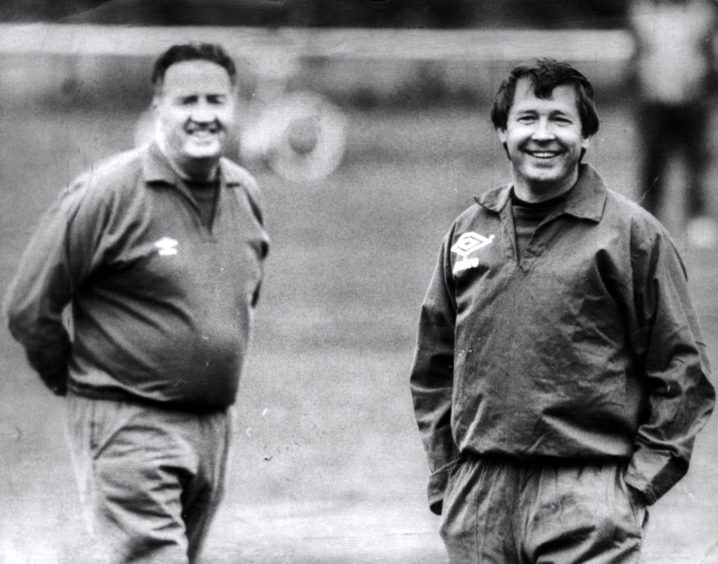

Let’s also remember that Ferguson was working with much less money, profile and fan revenue at Pittodrie than when he eventually moved to Manchester United at the end of 1986. Despite the Dons’ success, they weren’t splashing the cash on multi-million-pound signings, nor raking up vast reserves of television cash. The manager and his assistant, Archie Knox, had to keep a tight control on expenditure and the wonder was that they stayed so long in Aberdeen, given the number of clubs who strove to woo them away.

Compare that with the scenario when he switched to Old Trafford and began the lengthy process of ditching the deadwood and telling the nightclubbers to bin their Mojitos and sling their hooks.

Ultimately, he was at the helm of another remarkable period of ascendancy, but he toiled at United for nearly three years, narrowly escaped being handed his P45 with an intervention from Bobby Charlton, and only began disproving the sceptics with the emergence of a new team in the early 1990s.

Would he have been in any position to spark in England without all the knowledge he acquired at Aberdeen? No, he wouldn’t. Would he have thrived under Sir Matt Busby and placed his faith in a blend of youth and experience if he hadn’t experimented with that formula under the Northern Lights?

Just as he thought the world of Teddy Scott and the other Dons scouts who laboured tirelessly off centre stage, he relished the work done by their counterpart, Eric Harrison, and his colleagues in the north west of England.

None of this is to disparage or underestimate the fashion in which Ferguson prowled into the pantheon at Old Trafford. He dominated the Premiership for more than two decades, brushed off so many different challenges and threats from other clubs, including Liverpool, Newcastle United, Chelsea, Arsenal and the “noisy neighbours” at Manchester City and ensured that phrases such as the “hairdryer treatment” and “Fergie time” entered the sporting annals.

But still, the reality is that United were a global brand before he arrived and they are still the same now, even if the front-page headlines have focused recently on fans invading the stadium in protest at the perceived failings of the current club owners, the Glazers.

Aberdeen, in contrast, are Scotland’s third or fourth biggest club, based in the city with their country’s third largest population.

Whatever ambitions the Class of 2021 might harbour in the future, the Dons are a medium-sized organisation, albeit one with a grand heritage and a willing determination to remain part of their community. They might have snaffled more European silverware than any other Scottish club in history, but only the Micawbers in our midst would ever imagine it will happen again.

And a large part of that is a direct consequence of Alex Ferguson’s determination to Never Give In!

The new film will be on cinema release from May 27.