In a guest piece for our From The Archives blog, Courier farming editor Ewan Pate looks at Dundee’s historic ties to a major ranch in Texas cattle country.

Every day dozens of unsolicited emails arrive on the Courier’s farming desk from all round the world.

Many of these, of course, are destined for the ‘junk box’, but just the other day I spotted the name Matador Ranch just before my finger reached the delete button.

I am glad I did because the Matador or, more accurately, the Matador Land & Cattle Company has almost as much to do with Dundee’s history as it does with its heartlands in Texas.

The email told how the modern day ranch, now owned by industrial conglomerate Koch Industries Inc, had just won the American Quarter Horse Association’s Best Remuda Award for 2013.

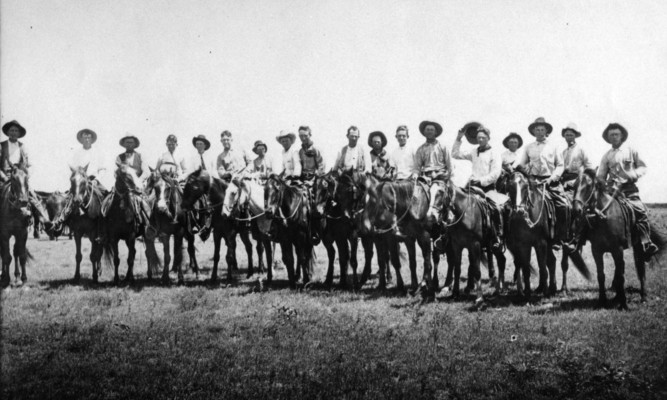

A remuda is the herd of horses from which cowboys choose their daily mounts, and it seems that the Matador has not let the tradition slip.

It is still a very considerable enterprise, with 130,000 acres devoted to raising cattle, but in its heyday under Dundee ownership it was a huge pioneering venture.

The Matador’s history and its name date to 1879 when Hank Campbell, a soldier in the Confederate army during the Civil War, persuaded four other investors to join him in setting up a ranch near Lubbock in the Texas Panhandle.

Only three years later they had sold the business lock, stock and barrel, to a syndicate of Dundee businessmen for $1.25m.

Investing in the American West had become a craze, with the then Earl of Airlie advising his fellow Scots to invest everything they could afford in this new land of opportunity.

The jute barons in Dundee had the money to invest, and they already had experience of carrying out mortgage business in the US. They had carried out a huge trade supplying sand bags and other textile goods to the Confederate States during the Civil War and, because of the lack of currency, had accepted land instead of cash.

And so was born the Matador Land & Cattle Co, with its registered office at accountants Mackay, Irons on Dundee’s Commercial Street.

It was actually one of three such cattle companies founded in Dundee at around the same time, but turned out to be the only long-term survivor.

Drought and hard winters later in the decade put paid to many of the other Scottish-funded ranching operations in the US, but the Matador came through the slump and flourished.

Hank Campbell stayed on as general manager and, under his stewardship, the Matador grew to include most of four counties and showed annual returns on investment of 20%. The ranch ran 40,000 cattle over 100,000 owned acres and a further 1.5 million acres of open range.

In her 2004 study, Claire E Swan attributes the Matador’s success to a combination of shrewd direction from Dundee and sound management in Texas.

Over the 69 years of ownership the company only had six chairmen in Dundee and five general managers in the US.

The real glory days of the Matador Land & Cattle Co were, however, to owe much to the outstanding contribution of its most enduring general manager.

Murdo McKenzie, the second of 11 children born on a small tenanted farm in Easter Ross, moved to Colorado as a young married man in 1885.

Six years later, and already an expert rancher, he was appointed general manager at the Matador. It was a post he was to fill from 1891 to 1911, and then following a spell on an even larger operation in Brazil from 1922 to 1937.

He was obviously a skilled cattleman and not frightened of change on the grand scale.

His first move was to reduce cattle numbers and improve quality by introducing Hereford bulls to cross with the Longhorn scrub cows.

He then realised that, even with the improvements, he was selling cattle at a discount.

They could be bred in Texas cheaply enough but, to be finished properly, they had to graze the better quality ranges found further north.

In the first year of this experiment his cowboys walked 2,000 two-year-old stores to grazings in South Dakota.

They stayed there for another two years, maturing slowly into prime beef ready for the Chicago stockyards.

The northward trail took 10 hard weeks.

However, by the next year McKenzie was able to put his cattle on trains for most of the journey, leaving only three weeks of droving to reach the pastures.

By the early years of the 20th Century the Matador Land & Cattle Company was sending trainloads of Texas-bred cattle to leased grazings across the Dakotas and up into Canada.

To sustain a trade which ended in the Chicago stockyards the company had also bought the 210,000-acre Alomositas ranch near Amarillo.

At its peak the company had title to 879,000 acres and owned 90,000 cattle.

McKenzie was so well respected that he was elected president of the American National Livestock Association.

President Theodore Roosevelt apparently called him “the most influential of American cattlemen”.

Flexibility was a by-word and later, as refrigerated transport became more common, many of the Matador cattle were slaughtered in meat plants nearer the ranges. The Chicago meat packers had become too greedy, it seems.

However, the Wild West was never far away. McKenzie was a strict disciplinarian and banned his cowboys from drinking and gambling out on the range.

In town it was a different matter, and tragedy struck when Dode, one of McKenzies’s three sons, was shot dead in a bar-room brawl.

As a further sign of the times the Matador Land & Cattle Company often employed ‘range detectives’. These were men tough enough to deal with rustlers, native Indians or settlers using their own methods.

The enterprise had its ups-and-downs but prided itself on a consistently better calving percentage than its rivals.

However, by the late 1940s it was becoming obvious that the days of the huge ranches were over. The Dundee directors knew that their land-holding would be worth far more if it was divided up into farmland, but decided it would be for others to undertake the task.

In 1951 the whole company was sold to Lazard Freres & Co for $18.9m. This brought a huge windfall for the shareholders, many of them still living in the Dundee area.

Not long afterwards the 130,000 acres at the core of the Matador Ranch were sold to present owners Koch Industries.

The ranching side of the business was improved by a massive project designed to control the mesquite tree. Over the years this scrubby plant had taken over whole areas of the range.

During the clearance operation it wasn’t unusual to find 10-year-old cattle which had never been branded.

The ranch now also has conservation and hunting enterprises, with its own hunting lodges. The quail shooting is claimed to be amongst the finest in the US.

The livestock enterprise is now based on Black Baldy cows. These are an Aberdeen-Angus cross Hereford hybrid, hardy enough to thrive under range conditions.

The ranch also has a pure herd of Akaushi cattle. These are a red-coated Japanese Wagyu type, and the stud produces bulls for crossing with the Black Baldy.

The offspring produce a premium meat which is sold under the Heart Brand label.

And of course it has its award-wining remuda of ranch horses.

All in all, it seems the Matador Ranch has always had quite a story to tell.