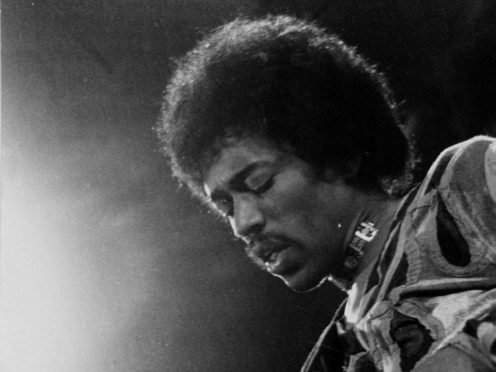

Scientists believe they have busted the myths that parakeets were introduced to the UK by Jimi Hendrix, or during the filming of a Humphrey Bogart film.

Using geographic profiling scientists mapped half a century of sightings of the bright green birds (Psittacula krameri).

They found no evidence to support any of the myths surrounding the birds’ origins in the UK, according to the study published in the Journal of Zoology.

The brightly-coloured bird has been in Britain for decades, although it is unclear how they were first introduced.

One theory is they were refugees from the film set of The African Queen, shot in Ealing in 1951, while another is that a pair were released by Hendrix on Carnaby Street, central London, in the 1960s.

Another theory suggests the winged-creatures kept at Syon Park escaped in the 1970s when a plane crashed through the aviary roof, while another blames damage to aviaries during the Great Storm of 1987.

This is despite sightings dating back to the 1869s, scientists say.

A new spatial analysis, backed by an extensive search of archived newspaper articles, found that Britain’s booming parakeet population has actually grown from numerous small-scale accidental and intentional pet releases.

Researchers from from Queen Mary University of London, UCL, and Goldsmiths, University of London conclude that intentional releases may have been encouraged from 1929-1931, and in 1952 by dramatic media coverage of fatal “parrot fever” outbreaks.

Scientists used geographic profiling to analyse spatial patterns of parakeet sightings.

The statistical technique was originally developed in criminology to prioritise large lists of suspects in cases of serial crime.

Worton Hall Studios, where the Bogart and Katharine Hepburn classic was filmed, Syon Park, and Carnaby Street did not show up prominently in the geoprofile of more than 5,000 unique records dating from 1968 to 2018.

Geographic profiling typically maps crime sites, like the location of murder victims’ bodies.

This is overlaid on a map of the area of interest to produce a geoprofile and narrow down the area where the perpetrator is likely to live or work.

When applied to biological data, the model can identify the origin sites of diseases or introduction sites of invasive species, like the parakeet.

Lead author Steven Le Comber said: “The ring-necked parakeet has become a successful invasive species in 34 countries on five continents.

“The fun legends relating to the origins of the UK’s parakeets are probably not going to go away any time soon.

“However, our research only found evidence to support the belief of most ornithologists: the spread of parakeets in the UK is likely a consequence of repeated releases and introductions, and nothing to do with publicity stunts by musicians or movie stars.”

Dr Le Comber has used the technique in a variety of ways which include mapping malaria outbreaks, Banksy paintings, Second World War bombs, and more.

A British Newspaper Archive search conducted at Goldsmiths found thousands of pages of news stories about parakeets written between 1804 and 2008.

However, search word combinations failed to locate a single item of news coverage documenting the escape or release of parakeets in the context of the four main origin myths.

Numerous sensational accounts of human deaths due to psittacosis infections were printed from 1929.

Study co-author Sarah Elizabeth Cox, postgraduate history student at Goldsmiths, said: “Scary health stories often prompt a strong public reaction – look at the late-1990s autism/MMR panic.

“It is easy to imagine the headlines of 1952, such as ‘stop imports of danger parrots’ leading to a swift release of pets.

“If you were told you were at risk being near one, it would be much easier to let it out the window than to destroy it.”