Ten years ago while excavating the site of a Pictish monastery on the outskirts of Portmahomack, Easter Ross, archaeologists made a curious discovery.

Several bones from the feet of cattle, some sharpened, were found mixed with small white pebbles, a curved knife and heaps of seaweed ash.

What they had discovered was a vellum workshop.

Early monks crafted their Gospel books and Bibles from vellum, a fine parchment made from the tawed hides of calves and cattle.

Secular books and charters were likely made from the inferior hides of sheep and goats.

It was a big industry.

In the eighth century, Ceolfrith, a Northumbrian abbot, commissioned three copies of the entire Bible.

Accordingly, his king granted land to raise a herd of 2,000 cows a huge outlay in those times.

The younger the cow the better the vellum and every spring young or new-born calves would be slaughtered for their precious hides.

Each calf yielded two pages (four sides).

A new Gospel book consumed the hides of more than 100 calves, and a new Bible some five times that number.

After the animal was slaughtered and skinned, the subsequent hide was washed and scraped clean.

Calcium oxide, known as lime and obtained by burning limestone, was needed to whiten the hides.

In the absence of local limestone the Portmahomack community turned to the seashore.

The shells of winkles and whelks and spirobis clinging to seaweed can be burnt, smothered in turf, to produce lime.

The skins were soaked in a tawing tank filled with lime solution then scraped and thinned some more before returning to the tank for a fuller immersion leading to their preservation.

Once limed and washed the skins were pulled taut on a wooden frame using pegs made from foot bones and small stone toggles.

The skin would then be further thinned and smoothed with a curved knife and variety of abrasive stones.

A cut in the parchment through a slip of the knife could be mended with needle and thread.

Each piece of vellum was then cut to size and handed to the men in the scriptorium.

A common misconception holds that monks wrote in books that were bound.

In fact, writing was done on individual sheets of vellum which were only later incorporated into a book.

Inks and paints, applied with a stylus, could consist of anything from soot to crushed apples.

When he was abbot of St Peter’s at Ripon, Saint Wilfrid of Northumbria, a man not known to do things by halves, commissioned a copy of the Gospels in lettering of the purest gold, done on purple parchment, bound in a gold case and studded with costly gems.

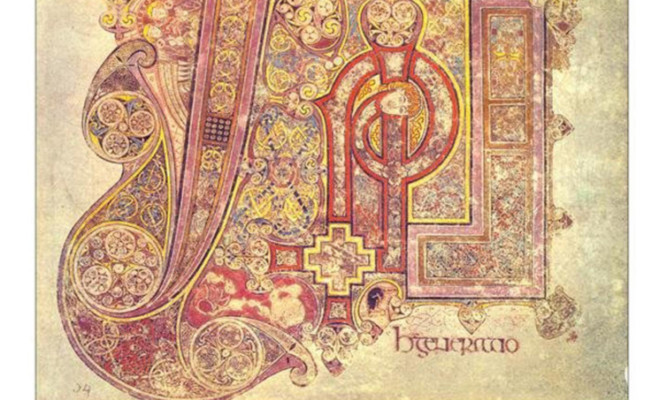

One of the great masterpieces on vellum is the Book of Kells, sometimes known as the Gospel Book of Columba one of Scotland’s first Saints.

Possibly originating from Iona, the book was found in Kells, in Ireland, and is now housed at Trinity College Library, Dublin.

A phrase that has echoed down to us from early times is ‘Spring is the cruellest season’.

The winter supplies were all but finished and yet the new year’s crops had not yet begun to bear fruit.

The inevitable sister activity of vellum production would have gone some way to addressing this.

Skilled butchers would work with the carcases, making sausages and blood pudding, or preserving the meat through salting, smoking or soaking in brine.

It would be no exaggeration to say that cattle were the chief source of portable wealth in early medieval Britain.

In the seventh century the formidable King Oswy exacted tribute paid in cattle from those areas under his overlordship.

It has been speculated that it was near Milfield, some eight miles south of the Scottish border, that these animals were collected, counted and evaluated.

The nearby site of Maelmin, dating from the period, comprised an enclosure encompassing 10 hectares.

It is recorded that Oswy pledged to build monasteries on 12 estates should he defeat the pagan king Penda in battle.

In 654, near modern-day Leeds, he did just that and it is safe to assume a sizeable percentage of the cattle corralled at Maelmin made its way to the vellum workshop at Lindisfarne and beyond.