They were the ‘super flats’ built in the Hilltown to tackle Dundee’s growing population which soon became a scar on the landscape.

A draft plan for the development of a city that was running out of space was drawn up 70 years ago by planning consultant Dobson Chapman.

Dundee Corporation warned the outward spread of the city had already caused “economic, physical and mental hardship due to travel difficulties”.

Further development outwards would only aggravate the problem and multi-storey properties nearer the city centre were the alternatives.

The Hilltown, Perth Road and Blackness were possible sites in 1952.

Multi-storey flats were eventually approved by the housing committee in 1955 and Dryburgh led the way when the first 10-storey block rose in January 1960.

Most of Dundee’s multis were built between the mid-1960s and early 1970s and there were 55 blocks dotted around the city by 1980.

By then, however, there was also a realisation that decanting people from slums did not necessarily mean solving social problems.

Only 11 high-rise blocks remain in the city and the Dallfield multis – built between 1964 and 1966 – comprise the largest-surviving development.

They consist of four 15-storey blocks nestling at the foot of the Hilltown: Dallfield Court, Tulloch Court, Bonnethill Court and Hilltown Court.

The four Alexander Street tower blocks in the Hilltown – Carnegie, Jamaica, Maxwelltown and Wellington Courts – were built in 1968.

The 25-storey Derby Street multis – Butterburn and Bucklemaker Courts – followed in the 1970s and stood tall near the crest of the Hilltown.

They were seen as a golden opportunity for people to escape the decaying tenements and enjoy space, light and comfort with great views.

Eventually, though, things changed for the worse.

For many years, the vast buildings had no security and very little maintenance, which led to crime, vandalism and the buildings becoming run down.

The Alexander Street multis were toppled in spectacular fashion upon becoming the first to be demolished in July 2011 with a £3.7m contract awarded to Safedem.

Plumes of dust and dirt could be seen from miles around, later clearing to show empty spaces in the area thousands of people once called home.

The rumble as debris came crashing down could be heard as far afield as Monifieth.

Some 135kg of explosives and 4,500 detonators were used in the operation with 600 homes and 50 businesses evacuated as part of the exclusion zone.

This included the congregation of St Salvador’s Episcopal Church, which stood in the shadow of the multi-storey blocks.

Church-goers puzzled over where to hold their Sunday service found a solution and were invited to bring a chair to Dundee Law where they re-enacted Jesus’ Last Supper.

“Have a Sunday off?” said Father Clive Clapson.

“No way! Worship is a priority.

“Our house eucharist won’t be our customary solemn high mass, of course, but from our vantage point above the city there’s no denying that it will be high church.”

Dundee Law had never been busier with hundreds of people heading to the city’s highest point for an eagle-eye view of the collapse.

Large crowds also gathered on the Tay Road Bridge, eager to watch the spectacle.

Following the towers’ demise, those living in the Hilltown area returned to the exclusion zone to find cars and buildings covered in dust from the explosion.

The Tay Road Bridge was subject to a rolling roadblock throughout the demolition before re-opening fully to vehicles shortly afterwards.

Work took place at the site for 20 weeks to remove and process the rubble from the four multis, which was recycled and re-used by the building trade.

The Derby Street multis were demolished in 2013.

Now there were only a handful of people still living there with many doors boarded up or displaying handwritten messages to inform posties the flats were empty.

But why did these concrete giants fall out of favour?

Then-city development director Mike Galloway broke it down further.

“Why did we build them?” he said.

“We built them because we had growing populations.

“We were trying to demolish Victorian slums, which had very high densities, and we had to re-house their occupants.

“We wanted to house them in the city, but we wouldn’t have had room to do that unless we built upwards.

“That was the main driver for developing the multis and, conveniently enough, it was also a very quick and relatively cheap way to build.

“We’re now left with the legacy of that – a situation where these buildings are very expensive to maintain.

“Their failure is affecting future planning policy. We want to see a lot more individual homes, semi-detached and four-in-a-block, which are popular house types.

“The multis are also expensive to maintain, so the economics are against them.”

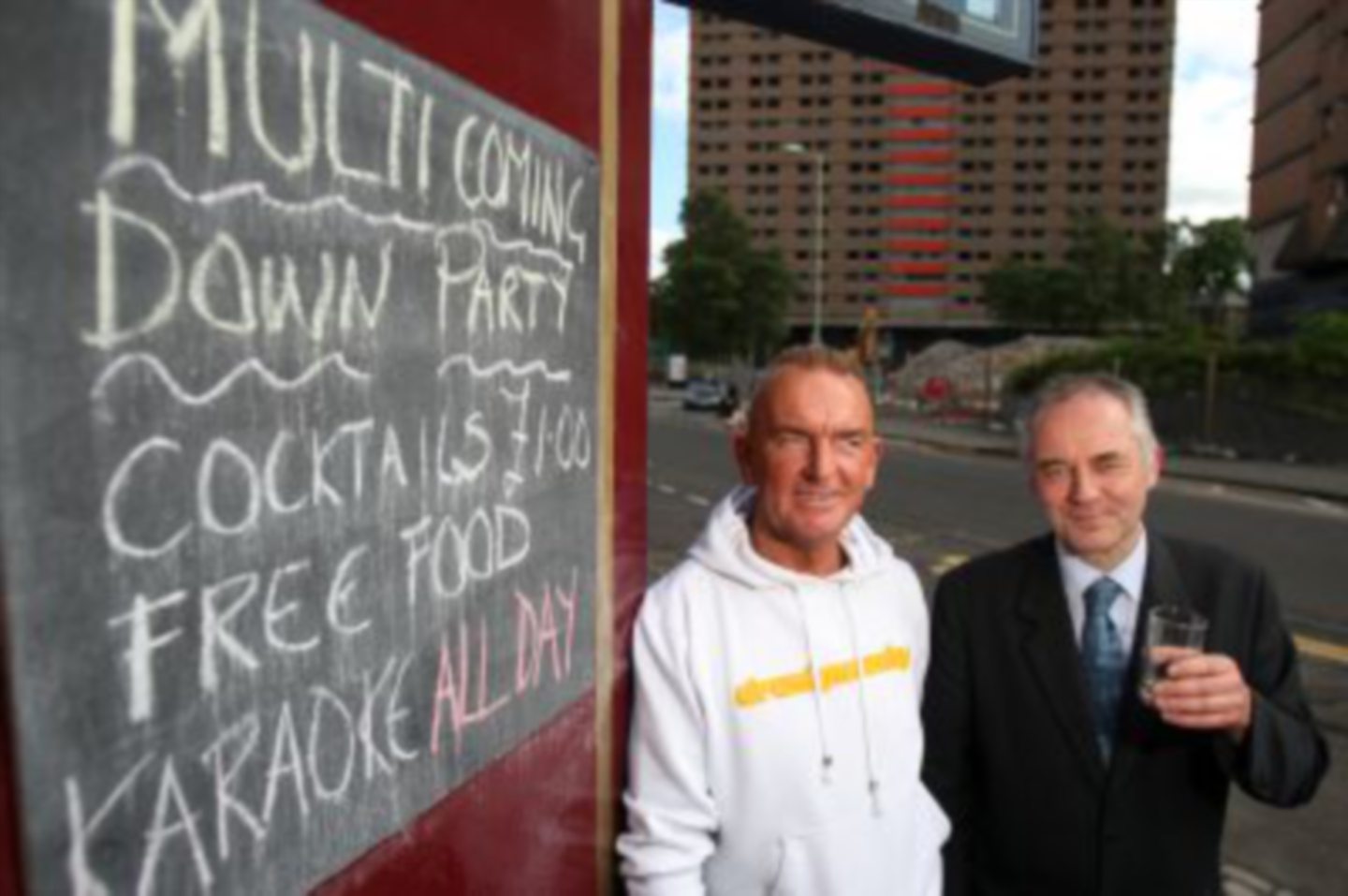

The Glenlivit Bar was closed during the Derby Street demolition before re-opening for a “multis coming down party” that captured the imagination of the community.

The Derby Street multis were arguably one of the most challenging demolitions because they were twin towers of 22-storeys each in a busy and huddled city area.

Butterburn Court was the ‘red multi’ while Bucklemaker Court was the ‘blue multi’.

Safedem dropped them both with masterful precision and 10,000 detonators.

A tiny church sat between the two blocks and despite 20,000 of rubbles falling in one fell swoop, it suffered only the slightest cosmetic damage.

The risk faced by St Martin’s in being damaged by thousands of tonnes of concrete crashing down around it became the subject of global media attention.

Print, broadcast and online journalists flocked to Dundee to record the nerve-wracking moments after the detonator buttons were pressed.

Down the towers came and although a corner of the church was struck by masonry from Bucklemaker Court, the damage caused was minimal and was promptly rectified by the contractors.

“I think someone up there was watching over us,” one of the Safedem experts said.

The demolition was part of a regeneration project for the Hilltown area, although the Dallfield cluster from the 1960s has managed to survive the skyline purge.

The properties remain popular with tenants, having been spruced up with a multi-million-pound investment that should ensure they are fit for another generation.

More like this:

Dundee’s Ardler multis were a high-rise dream that turned to dust

Carolina Port: When chimney stacks that dominated Dundee came tumbling down