They were the friendly young Dundee nurses who led a secret life as gunrunners for the IRA.

Lena and Kathy McDonald lived with their mum at 31 Brook Street.

They often helped out in the family’s fruit and vegetable shop across the street.

Lorries would sometimes draw up in the middle of the night to unload crates.

But it was only later when the police turned up that it emerged the night time visitors had prices on their heads.

The crates from the shop were packed with guns and ammunition which were being shipped through Liverpool and Glasgow to IRA rebels fighting the British forces in Ireland.

How did the Dundee sisters become supporters of the Irish Republican cause?

On the 50th anniversary of Ireland’s Easter Rising of April 1916, a Dundee Evening Telegraph article in 1966 told how it was because of a holiday in Ireland in the early 1900s – plus the influence of a Donegal born grandfather – that the sisters became interested in the Irish struggle.

Soon afterwards, they joined the Scottish Brigade of the IRA , which also had a Fife and Kinross-shire presence, and began to collect arms from dealers in Dundee, Carnoustie, Broughty Ferry and Monifieth.

“Our first gun cost only 3s 6d,” recalled Lena, “but later they became a lot dearer.

“People smuggled arms to our shop in Brook Street in all sorts of ways – sometimes hiding the bullets in papers of fish and chips.”

Eventually a crate of rifles discovered by the authorities in Glasgow was traced back to the McDonalds. Lena, then aged 19, was arrested.

She was taken to the jail in Dundee’s Bell Street, but they had to let her go because of insufficient evidence. She returned to her gunrunning and was arrested again.

This time she went to prison in Edinburgh and her older sister, Kathy, took charge of the rebel operations.

Later Lena returned to the less hazardous job of nursing. With their mother, she and her sister worked in the maternity hospital in Dundee before they emigrated to Canada and the US.

The Eire government later honoured them with a war pension and two service medals, which praised their “bravery, nobility and sacrifice during the independence struggle”.

New book tells untold stories of ‘working class’ Irish Republicans in Dundee

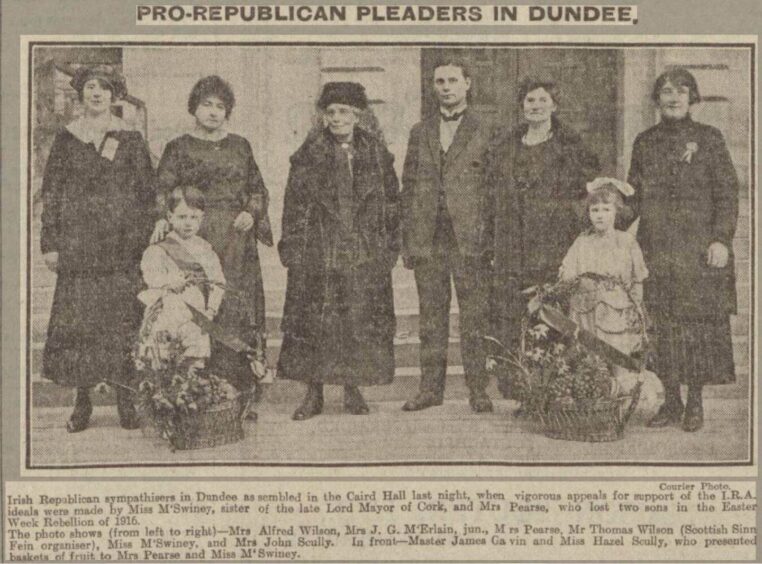

Women like Lena McDonald, who were based outside of Ireland, have been long “overlooked” when it’s come to studies of Irish Republicanism and the Easter Rising of April 1916, which paved the way for Irish independence in 1922.

This has been largely down to relatively few sources being available about the role of everyday, working and middle-class women.

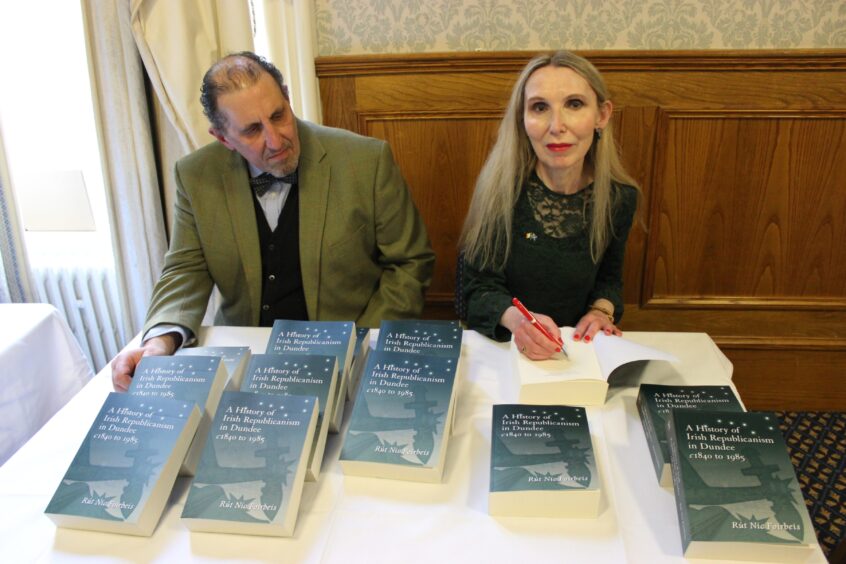

Now, Dundee author and independent historian Ruth Forbes is hoping to change that with the publication of her first book – A History of Irish Republicanism in Dundee c1840 to 1985 – which includes the story of the McDonald sisters.

Not only is the book the first history of Irish Republicanism in Dundee, it’s the first local study of Irish Republicanism in Scotland, which makes it unique.

It charts the peaks and troughs of Irish and other radical activity in Dundee against a wider historical backdrop.

It’s also the story of the struggle to establish an Irish Republic, and how support for that cause – including support for physical force – waxed and waned in the city over almost 150 years.

How did Dundee author Ruth Forbes become interested in Irish Republicanism?

Born and bred in Dundee, Ruth is a former pupil of Barnhill Primary and Grove Academy who first got into “doing” history rather than just reading about it through the Dundee Oral History Project in the 1980s.

The then innovative government-funded community programme for unemployed people inspired her to study history as a mature student at Dundee University from 1990-95.

She went on to do a PhD in Victorian culture at Dundee, and also studied librarianship at Strathclyde.

She’s always had an interest in social justice and politics.

She puts this down to growing up in Dundee from a working-class background.

Her father, who went into teaching as a mature student, always encouraged her to “get involved” in issues she cared about.

Today, she supports other “progressive causes” including the Dundee Nablus Twinning Association, Tayside for Justice in Palestine and the Radical Independence Campaign.

While she’s always had an interest in Irish Republicanism, it’s only been through the digitisation of the Irish Military Service Pension files and the British Newspaper Archive – owned by Findmypast/DC Thomson & Co Ltd – that the practical side of research for her new book has become viable.

‘Overlooked’ part of Dundee history

She also feels it’s become more acceptable to write about Irish Republicanism now that ‘The Troubles’ are in the past.

“I’ve been interested in Dundee’s Irish Republican support for quite a while because I always thought it was an area that was overlooked,” said Ruth, who has Irish ancestry on her father and mother’s side, around six generations back.

“Lots of people I knew when I was growing up were interested in it.

“I think perhaps because it was such a controversial area at the time, historians tended to shy away from it.

“I thought with the peace process and all that it’s become ‘safe’ to write about it.

“But I also wanted to get in there before it’s colonised by academics.

“Although I come from an academic background, first and foremost it’s written from the perspective of being an ordinary Dundonian. It’s about the ordinary working-class people and the support many gave.

“It’s the first in-depth examination of Irish Republicanism in Dundee and identifies where the interweaving strands of radicalism, nationalism, republicanism and socialism converged and diverged.

“It explores dynamic tensions within and between the Irish national and other radical movements, along with the critical moments when national and social interests coalesced into a single struggle.”

Why did so many Irish immigrants settle in Dundee?

The “big push” that drove many early Irish immigrants to Dundee, Glasgow and elsewhere was the Great Famine of 1845-52, seen by many as an outgrowth of British colonial policies.

The potato crop, upon which a third of Ireland’s population was dependent for food, was infected by a disease, which led to a period of starvation, disease and emigration for millions.

Dundee’s jute industry attracted weavers from areas including south-west Ulster. By the mid-19th Century, 20% of Dundee’s population was Irish-born.

As support for republicanism and nationalism grew to free Ireland from British rule, support also grew in Dundee.

Ruth investigated the “secretive” Fenian organisation and the Irish National Land League which had support in the city.

Easter Rising leader James Connolly in Dundee

People are often aware that Irish Labour Party founder James Connolly lived in Dundee with his brother.

In 1889, Edinburgh-born Connolly left the army and settled in Dundee, where he took an active interest in socialist politics and trade union rights.

He later became Dublin commander of the Irish Citizen Army and was executed by the British for his leading role in the Easter Rising of 1916.

However, Ruth was keen to highlight the “minor players” from working-class backgrounds whose stories – along with that of Dundee in general – have often been overlooked.

“There was a lot of fundraising for the Irish cause going on in Dundee,” she said.

“People raised funds for the Land League. People also raised money in the 1920s for arms, for guns, for gunrunning.

“The story of the McDonald sisters is quite well known in Dundee-Irish lore.

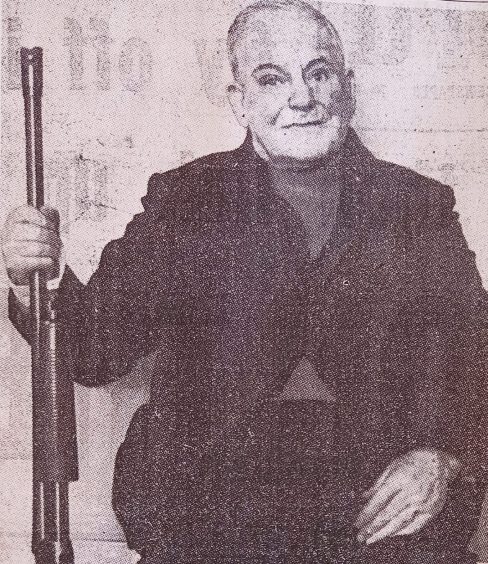

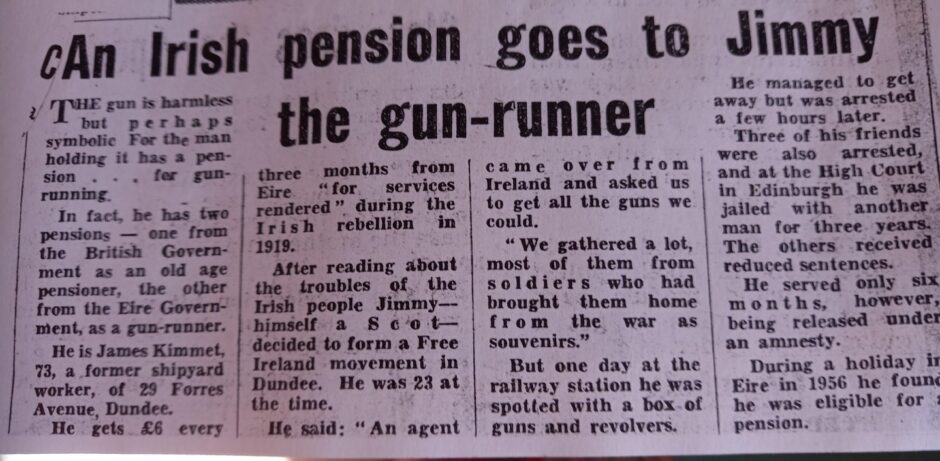

“But it wasn’t just about Lochee. One of my grandfather’s neighbours in Kirkton was also arrested in 1921 for gunrunning.

“I think that’s one of the things that maybe got me interested as well.

“There was also Irish Republican support in Dundee for what was actually happening more in the late 1970s and early 1980s during the time of the hunger strikes and the protests in prison.

“There was quite a lot of activity going on – mainly solidarity work.”

Irish heritage influences language, culture and politics in modern Dundee

Lochee has a very strong Irish identity because of the high number of people that came to work in Cox’s Mill, said Ruth.

But other parts of Dundee also had high concentrations of Irish workers including the Scourin Burn area, Hawkhill, Blackness Road and the Hilltown.

Dundee’s Irish influence has since become part of the city’s identity.

Some say the ‘eh’ sound of the Dundee accent can be traced to Ulster.

“Someone once said to me – try saying ‘I died for Ireland’ then say it in an Ulster accent and you get ‘Eh dehd fer Ireland’, which sounds Dundonian,” said Ruth.

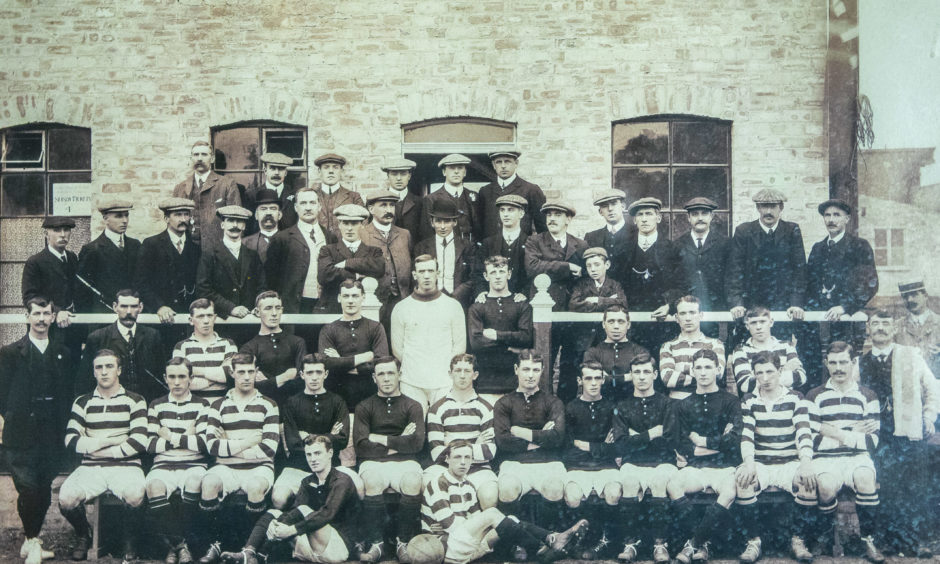

In 1909, local businessmen with Irish origins founded Dundee Hibernian.

In 1923, the club’s directors changed its name and colours to Dundee United to widen its appeal beyond the Irish Catholic community.

‘Dundee-Irish’ simply became ‘Dundee’

Scottish and Irish identity also became closely intertwined in a way that perhaps didn’t happen in other parts of the UK, she said.

Ruth added: “When people said to Irish people ‘why don’t you go back home?’, they would say ‘this is my home. I’m Scottish – and I’m Irish’.

“There was also the relationship with England and the British Government. Many people saw Scotland as having a similar kind of reason for wanting to be independent.”

A History of Irish Republicanism in Dundee c1840 to 1985 by Ruth Forbes is out now, £15, published by Tippermuir Books.

Conversation