Forgotten sketches show how plans were made to turn a derelict garage into Dundee Contemporary Arts.

Nethergate Garage was owned by George McLean and offered used cars alongside services like “high pressure greasing, washing and valeting”.

The showroom and yard beside St Andrew’s Cathedral was taken over by Tayford Motors and remained in operation until 1978.

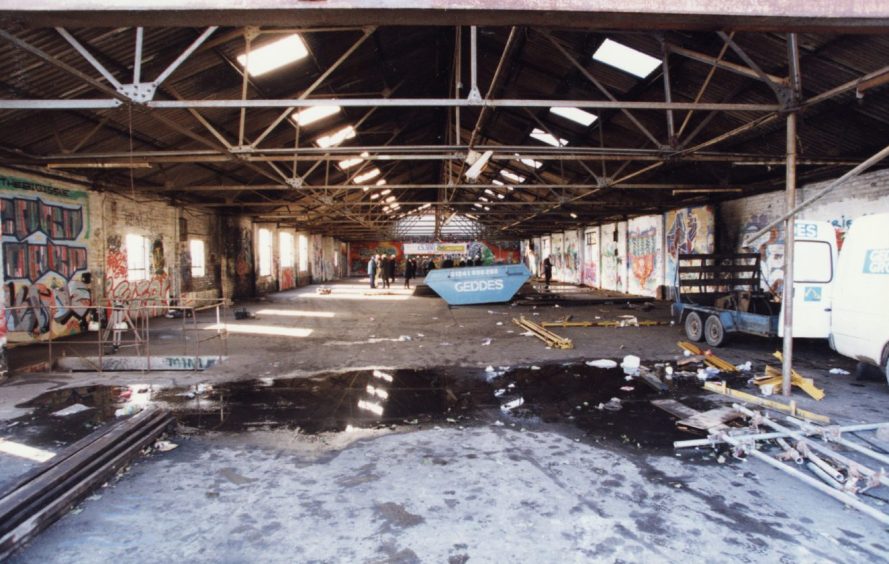

It was left to the mercy of decay.

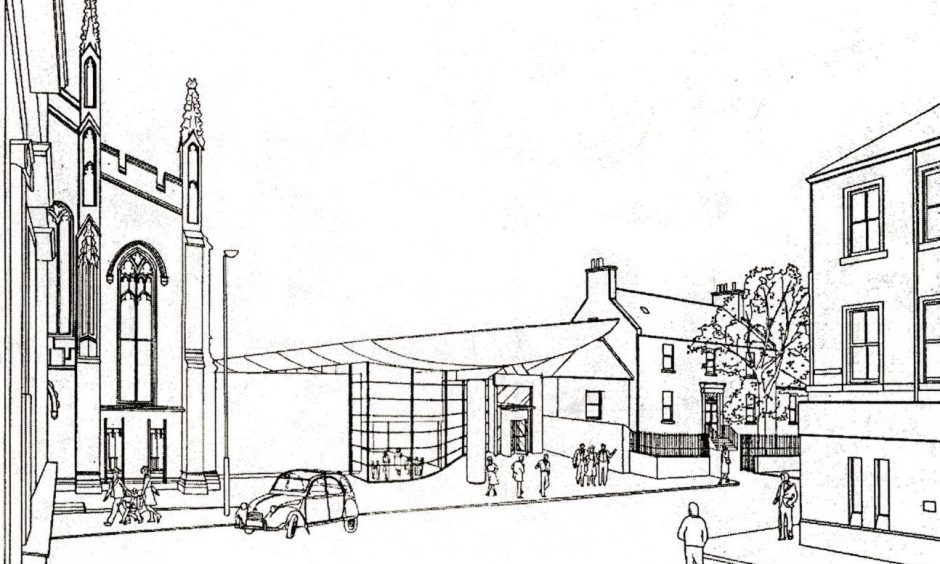

Planning applications were lodged with Dundee District Council to redevelop the site with a mix of uses including offices and a nightclub in 1986 and 1987.

All were thrown out for one reason or another.

The former garage became used by skateboarders and BMX riders.

John Buultjens spent his teenage years riding over make-shift ramps at the derelict site on a journey to becoming the face of the most famous BMX brand on the planet.

His rags to riches story would mirror the fall and rise of the building that would become DCA.

Where “high-pressure greasing” was replaced by grease paint and cars were replaced by stars.

The garage was gone but the DCA would soon be off and running.

History of DCA project

The project started life in November 1994 with a price tag of £1 million.

Labour administration leader Kate Maclean said the demand for such a centre was one of the key issues identified during consultation on an arts strategy for Dundee.

It was envisaged as part of an “arts and recreation quarter” with the nearby university, art college and Dundee Rep Theatre.

She said the centre would seek to attract to Dundee the kind of prestigious exhibitions which go to Glasgow and Edinburgh.

There was plenty of gnashing of teeth.

Tory group leader Neil Powrie said his group believed there was no real need or demand for any new arts centre in Dundee.

“The ability of the Labour councillors to concoct a never ending scheme of grandiose white elephants never ceases to amaze me,” he said.

“This is an election stunt promising cream cakes with council tax payers having to pay.”

The cost of construction had risen to £8m when approval was granted for the project in June 1996 following a vote supported by Labour and the SNP.

Some £500,000 would be contributed by the council to the capital costs with the rest of the funding coming from external sources.

With the city council, an independent board of trustees and academics on board, it set a tone of partnership that would be copied by many projects to come.

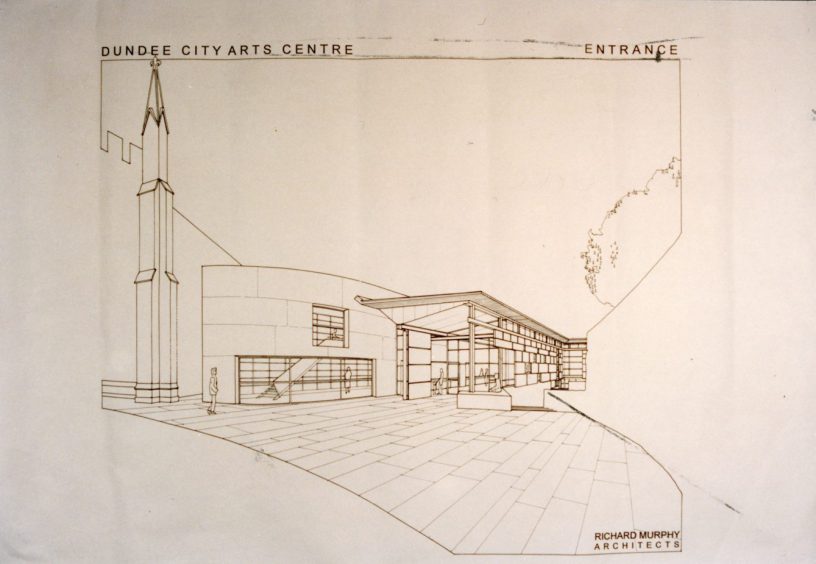

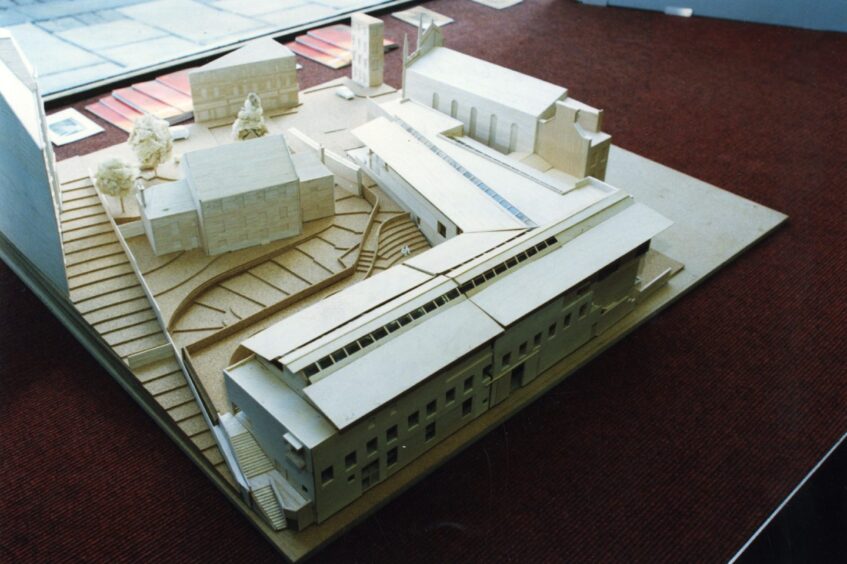

A competition was launched seeking an architect to design the arts centre.

The building would include two galleries, two cinemas, a printmaking workshop, research centre, activity room, shop, public meeting room and a café bar.

Some designs were well over budget

A striking design by Edinburgh-based Richard Murphy which “stuck to the design brief rigidly” was selected from eight entries by a panel of judges.

“It is a tricky site with a very narrow frontage but we have tried to draw people into the building using light,” said Mr Murphy.

Some architects who entered the competition were disqualified because they “let their imagination run riot” with designs “well over budget”.

The rejected entries were consigned to the dustbin of architectural history.

The project was able to get off the ground thanks to a massive cash injection of £5.4m from the Scottish Arts Council in October 1996.

Further funding came from Scottish Enterprise Tayside, the University of Dundee and the European Regional Development Fund.

Mr Murphy said the former garage was an eyesore but was in the South Tay Street conservation area and had “historical walls” which were to be retained.

Building work started in March 1997.

Dundee firm Torith won the construction contract.

A fragment of the city walls was retained

Mr Murphy discussed the thinking behind the design which began life as a “doodle on a train to Shropshire”.

The Courier said: “The exterior marries the red brick of the existing warehouse with green walling panels of pre-patinated copper.

“At the rear, where the car park is located, a fragment of the former seawall is used, and there is also a fragment of the historic Dundee city wall at the entrance.

“For the visitor, the first impression is of light and space as the building opens up before them.

“Mr Murphy explained that the idea was to get as many people into the building as easily as possible, and, once they’re there, to interest them in the various activities that are going on.

“For example, someone leaning on the bar can catch a glimpse of what’s going in the cinema through narrow windows, and, in the larger of the two cinemas, a 230- seater, the public look south to the Tay before the screen comes across, giving them a view of the world outside before and after each film.

“The social space is the café bar at the corner of the L-shape, which opens onto a terrace and auditorium with a poet’s pulpit, for good measure.

“The public entering from the Nethergate go past the shop and progress to the galleries.

“If they go down one level, they reach the café and can see the workings of the print studio, the Tay and the two cinemas.

“There are the ‘boffins in the basement’ where the university centre is housed.”

A bucket of ice and a ukulele

A George Wyllie event, A Bucket of Ice, was the DCA’s first artistic programme.

It took place on the terrace outside the unfinished building in December 1998.

It had not been an easy job getting it, since the pub which promised the ice had shut.

“Ice just seemed appropriate for Dundee,” he said, given the city’s link with whalers and the Discovery.

Pieces of ice were handed round to the watching crowd before he picked up a ukulele and sang two songs about stone and air.

It was clear life wouldn’t be dull at the DCA.

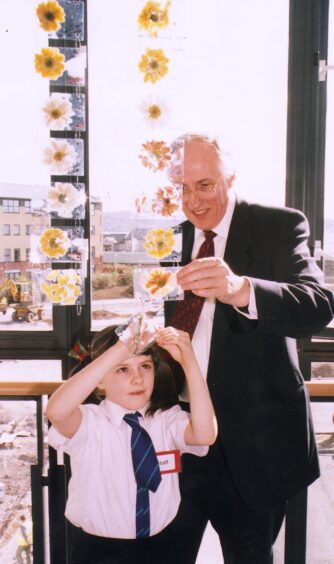

Scottish Secretary Donald Dewar did the honours at the official opening on March 19, 1999, predicting DCA would boost the city’s economy.

“It’s a building full of excitement and interest which will intrigue and excite people the way an arts centre ought to be able to do,” he said.

“This is just one element in the social and cultural renaissance taking place in Dundee.”

Charles McKean, professor of Scottish Architectural History at Dundee University said DCA was “one of the best new buildings to be found anywhere in Europe”.

DCA became an overnight success

Total attendance in the first 12 months was 350,000.

That was more than the 100,000 predicted in the business plan before its opening.

Scottish Arts Council chairman Magnus Linklater said: “The location and design of DCA, for which much of the credit must go to its architect Richard Murphy, means it has become an integral part of the fabric of Dundee city centre.”

It is often lauded as the project that kick-started Dundee’s regeneration.

Conversation