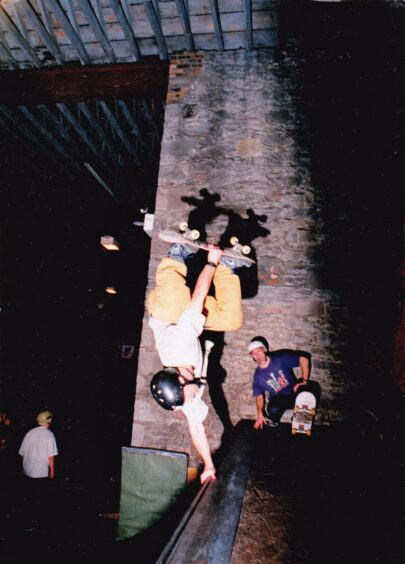

Whoever said there’s no such thing as functional anarchy has clearly never heard of The Factory skate park in Dundee.

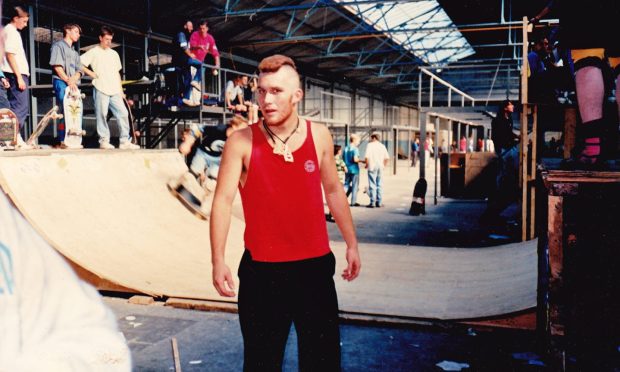

Formed first in an abandoned warehouse in Stobswell in 1987, The Factory began as just that – an old factory where a few determined Dundee skaters had built some ramps.

It was also Scotland’s first indoor skate park, in the loosest sense of the word ‘indoor’, with leaky ceilings, no windows and no power.

But for Dundee Hardcore Skate Squad (DHSS), it was a perfect place – and ‘planning permission’ was a phrase to be conveniently forgotten.

“We weren’t really breaking and entering, because the place had no windows,” reasons city skater Rick Curran, who was one of the five DHSS members who helped found The Factory over three decades ago.

“You could sort of just climb in!”

Yet aside from worrying their mothers, the merry band of young skaters didn’t do any harm to their Arthurstone Terrace Factory.

On the contrary, they ‘acquired’ some wood and fixed the place up, for no other reason than to have a decent place to skate in peace.

“One of the guys climbed up and ran electrical wiring, so we had strip lights rigged up over the ramps and things,” recalls graphic designer Rick, 51. “So we could use it in the winter and at night time.”

‘We’d sleep on the ramps and skate until the fuel ran out’

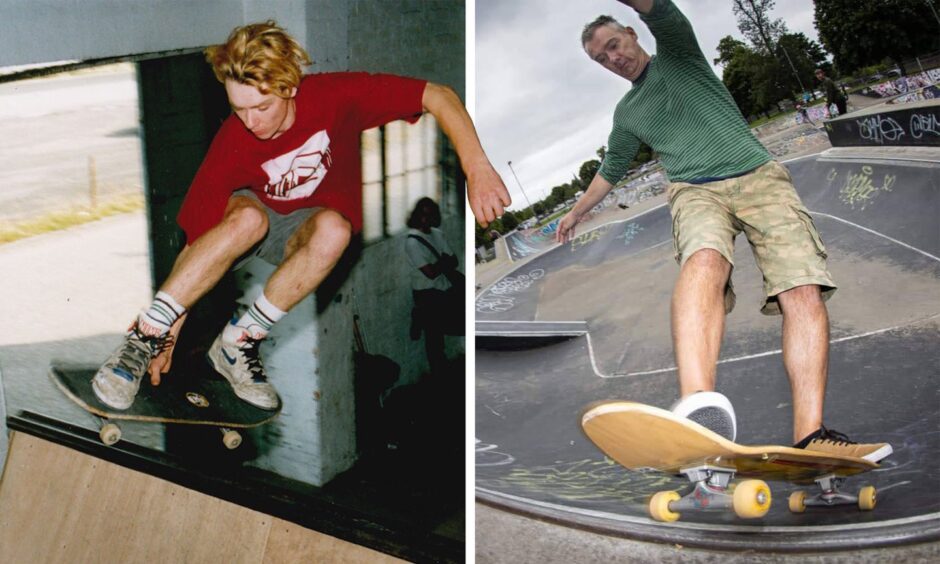

Scott Malcolm, another member of DHSS who still skates in the city’s Dudhope Park today, has fond memories of nights spent in that first Factory.

“For the time that the first Factory was around, pretty much every weekend of mine was spent there,” he says.

“We even slept in there a few times. I can remember a couple of times, being in a sleeping bag on top of a ramp. Not very comfortable, but it was just what you did!

“It sounds really dodgy now, sleeping in an abandoned factory, but we’d run the generator to provide some basic lighting, and just skate until the fuel ran out.

“You can’t really conceive of that happening nowadays from a health and safety point of view.”

Factory competitions drew skaters from across the globe

Despite its humble hospitality, The Factory revolutionised Scotland’s skate scene, attracting skaters from all across the country through the word-of-mouth rumour of a place to skate in the winter.

“We had two big skate comps in there,” explains Rick. “And people came from all across the UK for those.

“There were American skateboard pros and other European skateboarding pros who were in Scotland at the time too.”

He even recalls charging an entry fee of 30p for the competitions, to help fund the generator.

Sadly, after four utopic years of such organised chaos, The Factory was targeted by arsonists who burned the ramps, and eventually moved on to make way for council plans.

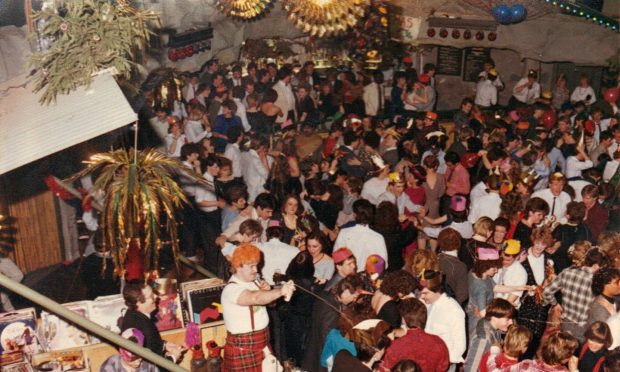

But by then it had become much more than a building – it was a self-sufficient community.

And for world-renowned BMX rider John Buultjens, who lives in California but grew up in Monifieth, that community was a lifeline.

Factory was home for ‘dysfunctional’ kids

“I’m adopted, and I was locked up for trying to kill my biological father in Glasgow before I came to Dundee with my adopted family,” explains John, 52, whose life story inspired motion picture Ride, starring Ludacris.

“To get into BMX was a release for me. And then finding all these friends that had the same passion for riding and skating and BMXing, it was like a brotherhood.”

For John, the skating and BMX scene gave a sense of home and friendship to the young people in Dundee who might’ve otherwise fallen through the cracks.

“You had kids from the multis, kids from dysfunctional families, taking all their anger into their skateboarding and their BMX riding. It gave them a place and it gave them a family.”

Yet he still remembers how often skaters were targeted by both police and football hooligans, making the city centre a no-go zone for the now-homeless Factory crew.

“There was this stigma of us being little city-centre terrorists,” he sighs. “One day, we were there playing around after they’d shut the Factory, and the cops took my bike off me. I’d done a tail whip on one of those big plant pots.

“And they arrested me for breaching the peace, destroying public property and endangering pedestrians. They dragged me into this little police station that used to be in the Overgate next to Greggs – and called my parents! I was 20 years old!

“Then beside Boots you would get all the casuals hanging about, and they would want to come across and beat up the skaters. Because they were bored.”

Skaters ‘took life in their hands’ against football hooliganism

Rick recalls run-ins with football hooliganism too, often provoked by nothing more than dressing “like a skater”.

“Going into the city centre, people would be getting drunk and looking for trouble,” he recalls.

“Unfortunately if you looked different in any way – not just being a skateboarder, but that was enough – then you’d be a target. Some guys took their life in their hands just going into town.

“Especially because some people would have the view that skateboarding is a kids’ activity, and we’d be a bit older, holding what these casuals would see as a kids’ toy.”

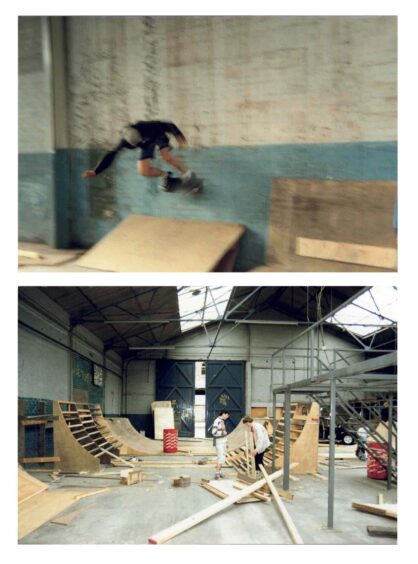

Fortunately for the skating community, the Factory soon found its second home in what would become the DCA building on Nethergate.

And there they proved to the authorities that they weren’t out for trouble; in fact, they could be an asset to the local area.

DCA clean up was rehab for skating reputation

“The DCA building was an absolute mess inside when we found it,” says Rick. “There were these old chipboard shelves that had disintegrated, and no glass in the windows, which meant the place was full of pigeons. So of course there was pigeon poo everywhere!

“We cleared all of that out and cleaned the space up and it got swept as clean as possible. It was still a grungy place in the end, but you know, it was looking good.

“So when the owner of that building came to see what was going on, he realised that we weren’t trying to break anything, and there was a positive thing we were trying to do. So I think that worked in our favour.”

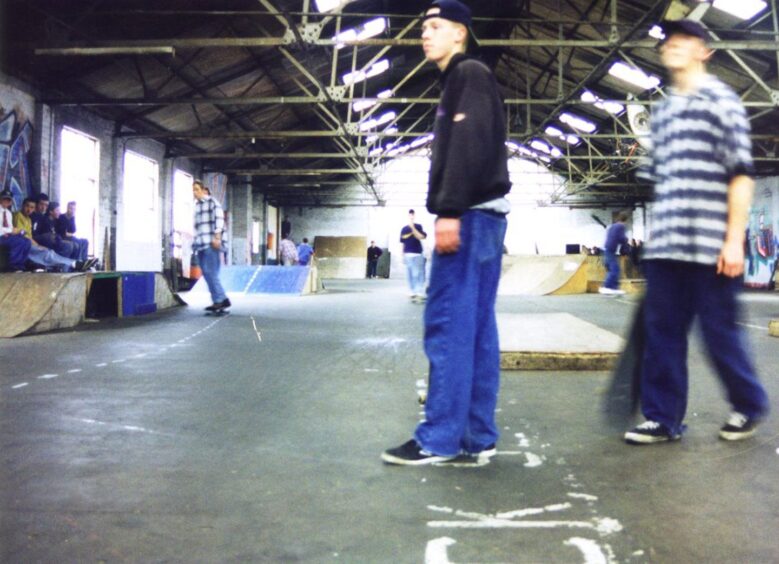

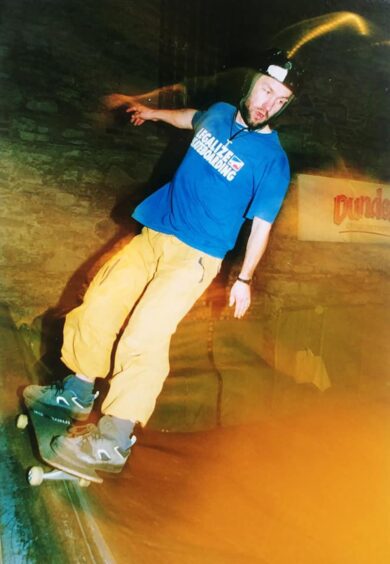

That skaters of Dundee thrived in that second Factory for two years until the building was sold to Dundee City Council to make way for the DCA.

“It was just amazing in there,” says John, who was firmly part of the skate community by then, known as ‘the one on the bike’.

Snow Patrol musician was DCA Factory regular

He describes the DCA Factory as a hub of not just skating and BMXing but of art and photography as well.

“It was all built ourselves. The city never helped, and the people there were so inspiring.

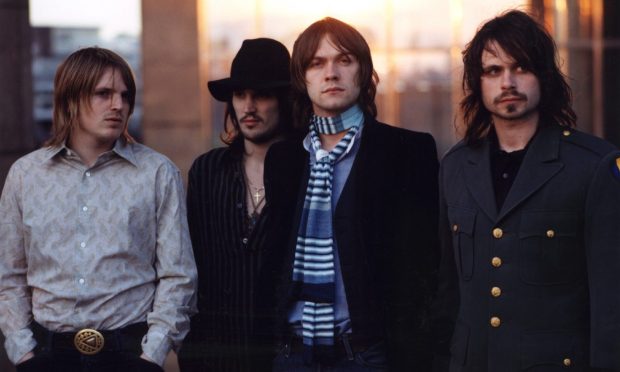

“Tom Simpson, who went on to do Snow Patrol, would come in and do all the graffiti. If you pulled some of those white walls down now, some of the original graffiti would be in there.

“It was such a special place. Everyone went on to create amazing lives for themselves.”

Thankfully, even though the homemade ramps of the DCA Factory had to be dismantled when the building was sold, the skaters’ clean-up effort had rehabilitated their reputation enough to help them secure an ‘official’ space, helped out by the Gate Church.

Erin welcomed by skaters at age of 8

That Blinshall Street Factory ran from 1998-2003, run by volunteers. It was here that Dundee woman Erin Schepers first remembers getting the bug for skating, back when it was still dominated by boys and men.

“I must’ve been about eight years old when I first went,” recalls Erin, 32. “I was shy at first as a young female. But the youth workers and fellow skaters would look out for me and give me tips and encouragement.”

It was this positive first-hand experience of Dundee skate ‘family’ which propelled Erin forward into a lifetime of fun on wheels.

“The scene was so welcoming and non-judgemental, which is why I liked to go. It’s why I still skate to this day,” she explains.

Now, Erin is far from the only woman in the city’s skate scene, after a huge amount of women and girls took up skateboarding and rollerskating over lockdown.

“It’s an exercise which doesn’t require a gym membership,” Erin notes. “You can be any shape and size and still skate.”

The changing face of skating in Dundee

After a successful run on Blinshall Street until 2003, a £1.6 million, purpose-built Factory with offices, cafes and showers was built in Douglas to house the city’s now-accepted skate scene.

A far cry from the run-down warehouse it began in, the final Factory lasted 16 years, closing in 2019.

For Rick, who now lives and skates in Dundee with his wife and their daughter, the landscape couldn’t be more different to when he first picked up a board.

“Skating is definitely way more popular and accepted now, which is brilliant,” he says.

“There’s more women and girls involved and now that it’s in the Olympics and things, there’s a much bigger argument for more skate parks and improving things.”

Passion Park – a new era for Dundee skating

Since 2019, there has been no indoor skate park in Dundee. But now, well-known Dundee skaters Lewis Allan and Scott Young are on the precipice of opening their new Passion Park on Gellatly Street after months of administrative hurdles.

The pair, who are both in their 20s, have learned from the likes of Rick and Scott Malcolm at the outdoor skate park in Dudhope Park.

And they’re looking forward to welcoming back the still-strong Factory era crowd as well as first-time skaters when they open their doors this year.

“The nice thing about skating is all the generations kind of mix together,” says Lewis. “Most people don’t ever seem to put it down even as they become an adult. They might be forced to grow up, but they’ve still got it there.”

For Rick, John, Scott and Erin, that’s certainly true. The Factory’s legacy lives on, as people who spent time there carry skating into their lives, between shifts and school runs.

“It’s a culture that people stay in, beyond getting married and having kids,” says Rick. “Folk may be getting older but they look back and remember the good times they had.”

“People tell me all the time to grow up,” says John, as he gears up for a BMX event “full of people in their 50s and 60s” in California.

“I think we need to stop telling kids to grow up. You’re an adult, grow down!”

Conversation