A pocket watch was frozen in time when the Broughty Ferry lifeboat Mona capsized with the loss of all hands on deck.

The watch stopped at 6.19am.

It was gently removed from the inside pocket of second coxswain George Smith, half wound and full of water and sand.

Was this the exact moment tragedy struck on December 8 1959?

A simple plaque on the side of the lifeboat shed serves as a daily reminder of the eight volunteers who never came home from the gale-lashed seas.

During her 24 years on the station, Mona had been responsible for saving more lives than any of her six illustrious predecessors.

The crew were widely experienced.

Between them they could produce RNLI medals for heroism.

Not that they would.

The only hope for North Carr was the Mona

The start of the festive season saw Scotland battered relentlessly by fierce storms.

Up and down the east coast, fallen trees blocked roads, rivers burst their banks, and the rail line at Carnoustie was blocked by sand drifts four feet high.

Ships everywhere were harbour-locked.

Out at sea, the half million candlepower bulb of the North Carr lightship still sent its reassuring flash four times a minute across the jagged rocks of Fife Ness.

The winds and 50-foot waves wreaked havoc in the early hours of December 8.

The massive cable tethering the lightship snapped as the storm worsened.

She began drifting towards the rocks at St Andrews Bay.

The Fife Ness Coastguard raised the alarm.

Anstruther lifeboat was closest but no vessel could get out of any of the Fife ports.

The Broughty Ferry station was called instead.

The Mona’s crew of eight tumbled out of bed at 2.45am and their footsteps were drowned out by the gale as they made their way along the lamp-lit streets.

Townsfolk slept on, unaware of the unfolding emergency.

The lifeboat was launched at 3.13am in the appalling weather.

The hopes of the North Carr sailed with the Mona.

Around 4am, the Coastguard got first sight of her as she cleared Buddon Ness, but she kept disappearing from view behind the mountainous waves.

The last time anyone heard from the Mona

She was seen heading south into St Andrews Bay at 4.45am.

Radio contact was maintained with the Mona before crewman John Grieve reported that she had cleared the bar of the Tay at 4.48am.

The difficult part was over.

Then there was silence.

North Carr’s crew were sent up on deck to look for its lights.

They couldn’t see anything.

That was the last message heard from the Mona.

At 5.39am Fife Ness coastguard Charlie Jones thought he saw the Mona’s lights.

They soon disappeared.

By a cruel twist of fate, the crew of the North Carr survived the storm, managing to halt its drift by dropping a spare anchor off Kingbarns at 6.45am.

By then the crew’s families and many others had begun to gather at the station.

The tragic fate of the men was discovered

William Philip, a barman at the Carnoustie Station Hotel, was taking an early-morning walk along the sands at Buddon shore when he came across the Mona.

The wheel was lashed to the boathook and the flagpole.

It seemed that she had turned over, perhaps several times.

The bodies of seven crew members were found in and around the lifeboat.

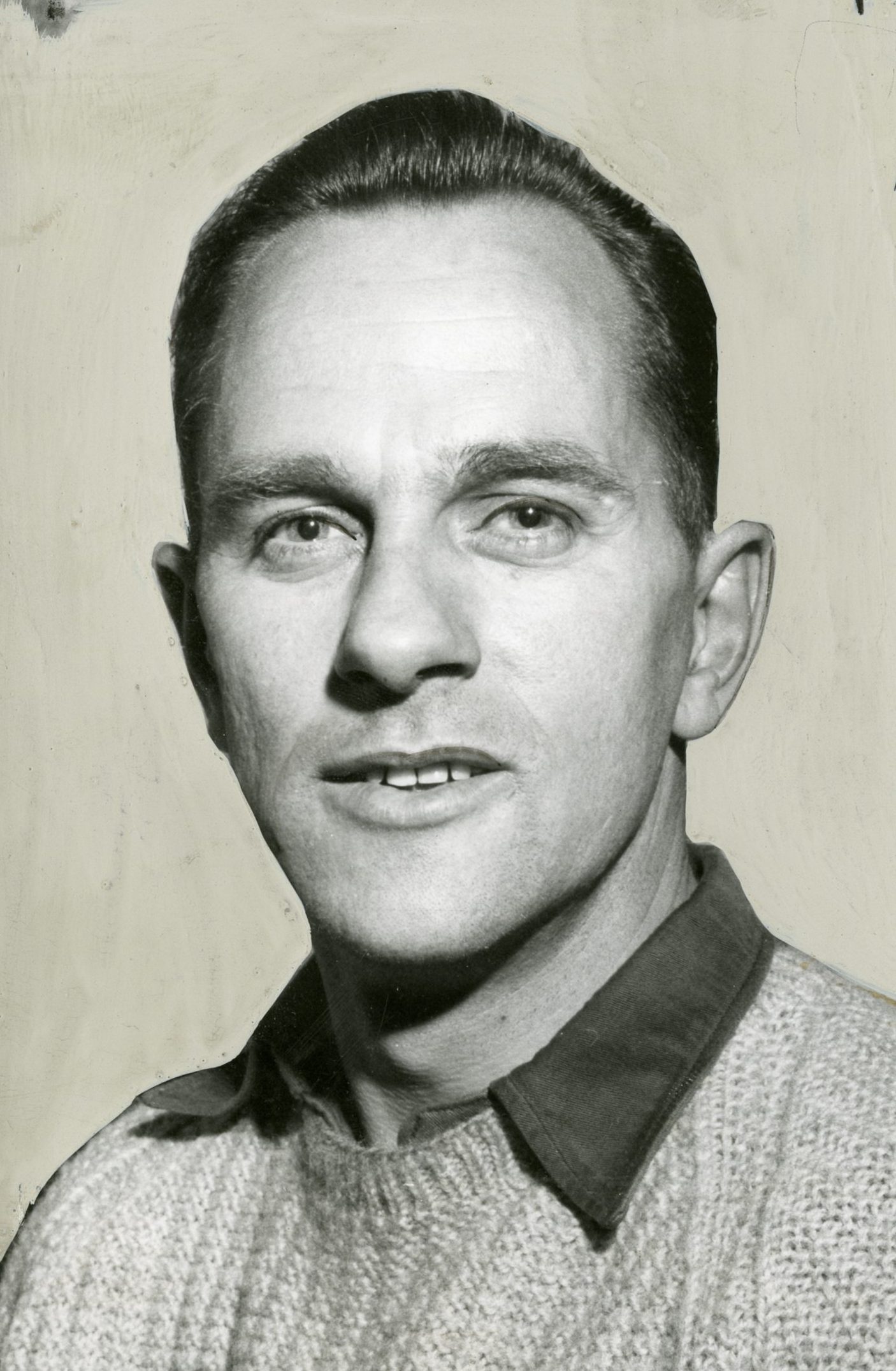

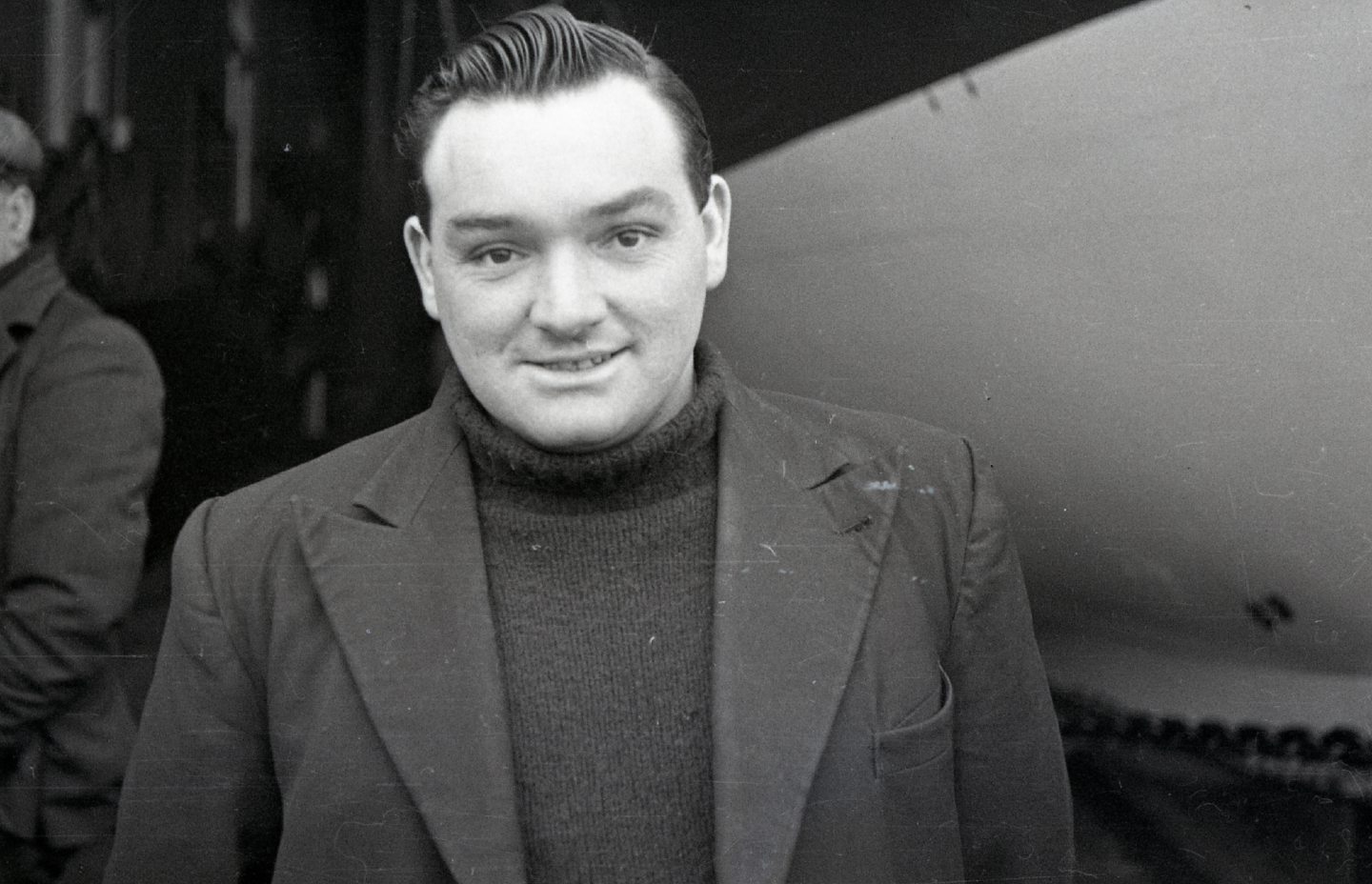

It had been Ronnie Grant’s first shout as coxswain.

He was 28.

Ronnie lived in Dundee’s Cotton Road with wife Josephine and baby daughter Gail.

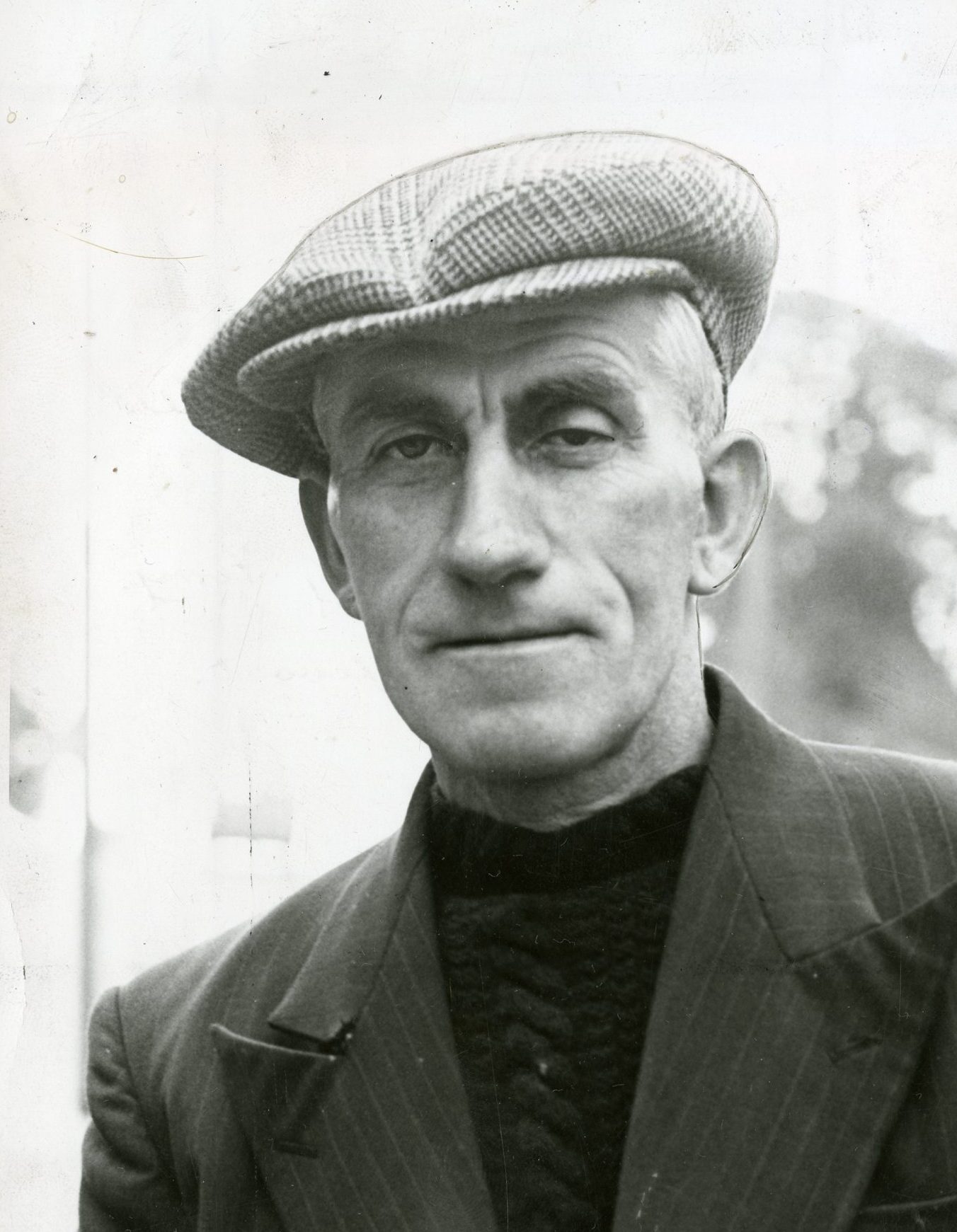

He succeeded Alex Gall, who was 56.

It was to have been his last shout before retiring.

Alex was married with a grown-up daughter.

Both men worked at the Caledon Shipyard in Dundee.

Second coxswain George Smith was a boatman at Dundee Harbour.

He received the RNLI bronze medal for his part in the rescue of the crew of an Aberdeen trawler that was wrecked on the Bell Rock in December 1939.

He was 53 and married with a grown-up son.

Father and son drowned in the tragedy

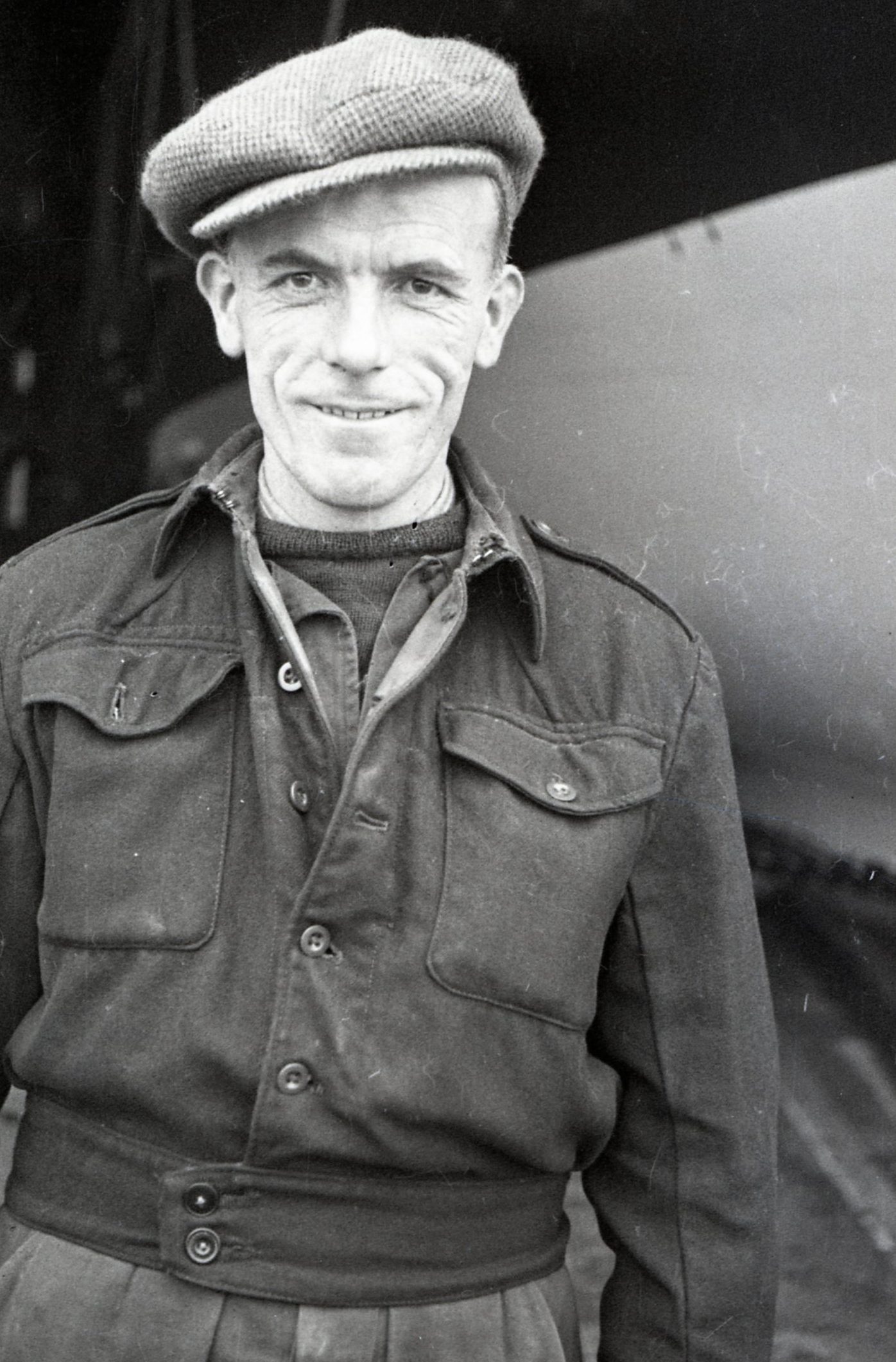

Mechanic John Grieve had been a member of the crew since 1922.

He joined from Arbroath where he worked with a marine engineering firm.

John also received a bronze medal for his contribution to the Bell Rock rescue.

He was 56.

John left a wife and two grown-up children.

It is a further tragedy that his son died with him on the Mona.

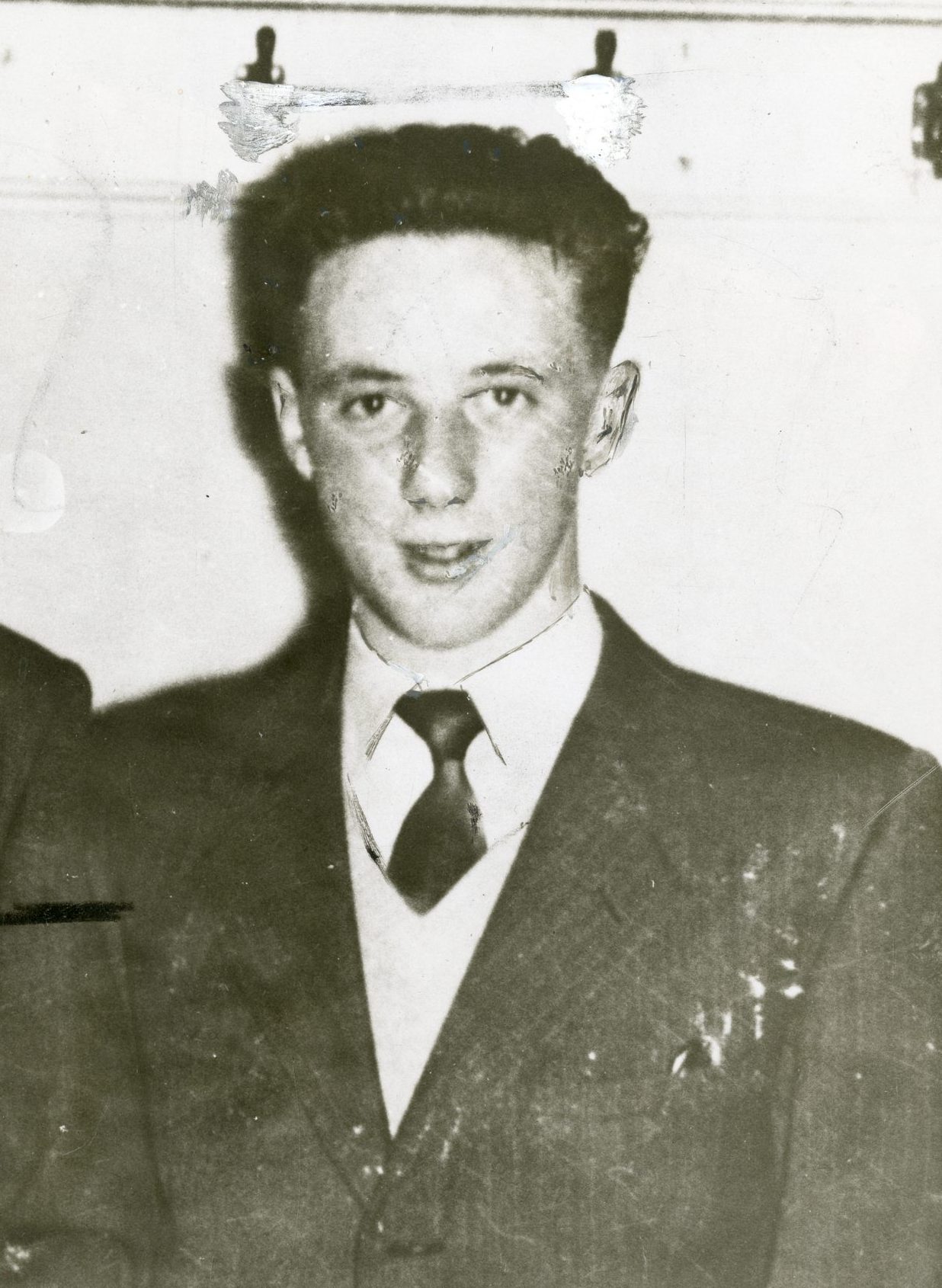

John was 22 and a crew member.

He was engaged to Smith Brothers shop assistant Kathy Stuart.

Crew member David Anderson lived in Broughty Ferry and was a plumber.

He was married with three sons aged 11, nine and six.

Assistant mechanic James Ferrier was 43.

He was married with two sons who were 11 and seven.

James was a driller at the Caledon and lived in Fisher Street.

The seven bodies were taken to the police mortuary at Carnoustie.

George Watson, the bowman, was never found.

He was 38.

His wife Winnie was a nurse at the Armitstead Convalescent Home in St Cyrus.

What happened to the Mona afterwards?

News of the disaster stunned Broughty Ferry.

A memorial service for the eight men was held at St James Church.

Across the road the RNLI flag was flying at half mast on the lifeboat shed.

Funds poured in from all over the country to help the families now lost without their main breadwinners, with more than £77,000 raised in less than a month.

By the time a relief lifeboat arrived at Broughty Ferry, two weeks after the disaster, 38 volunteers had signed up to form a new crew.

An official investigation described the Mona as “100 per cent seaworthy” and the findings suggested she had capsized in the gale.

But no-one knew the true story.

It remains a mystery of the deep.

The Mona was taken to a quiet beach at Port Seton in East Lothian.

She was destroyed by fire at 4am out of respect to the men who lost their lives.

The decision “for purely sentimentality reasons” was taken on the recommendation of Lord Saltoun, chairman of the Scottish Lifeboat Council.

“I could have altered the decision but I wanted the boat burned to nothing,” he said.

“I had seen the widows of the men it had lost.

“Who would have wanted to go out in that boat again?”

A timely tribute to the lifeboat crew

Every year since 1959 the eight men have been remembered with pride.

The community would pause to reflect.

A special and poignant moment came when a watch that went down with second coxswain George Smith was given a final curtain call in December 1998.

Lifetime member and former president Syd Smith was making his final performance with Broughty Ferry Amateur Operatic Society after 40 years.

When the Mona went down, Syd was taking part in a production of Princess Ida and, despite the loss of his father, continued to perform.

Adrenaline kept him going.

Syd treasured the watch ever since it was recovered with his father’s body.

“I see wearing the watch as a tribute to the men who were lost,” he said.

“I will be thinking of them as I play my last role before retiring from the stage.”

Time may have stopped for the crew of the Mona on that December morning in 1959, but the love and respect for the eight brave souls endures.

Conversation