Linoleum. A flooring type as misunderstood as it is mispronounced.

It’s responsible for the unmistakable squeak of trolley wheels in hospital corridors, as well as the terracotta visual assault that is your granny’s kitchen floor.

And linoleum is, as Kirkcaldy flooring boss Angus Fotheringham candidly admits, “the product that everybody walks over and forgets about”.

But despite its retro reputation, could a 21st Century comeback be afoot for humble lino?

‘Like watching paint dry’

Fittingly given its ‘forgettable’ nature, the origin story of linoleum begins with a man literally watching paint dry.

“You used to get a skin forming on the top of paint,” explains Angus, who is the UK and Ireland general manager at world-leading lino manufacturer Forbo, which Fifers may still fondly dub ‘Nairn’s’, though the company stretches well beyond the borders of Kirkcaldy.

“A lot of paint back in the day used linseed oil in its ingredients, and what was happening was the linseed oil was hardening when exposed to the air,” he continues.

“Anyway, a guy called Frederick Walton watched this happening in 1860 and thought: ‘That’s really interesting, that’s a tough surface – I could do something with that’.

“After mucking about with it, he patented the floor covering ‘linoleum’ in 1863.”

Before Sir Paul’s red carpet, there was woodgrain lino

Made by mixing oxidised linseed oil with pine resin, cork and pigments, linoleum took off as a floor covering which was flexible enough to floor uneven spaces where tiles would crack, durable enough to stand the test of time in high-traffic areas, and bacteria-static, making it perfect for use in the healthcare industry.

It was even used in living rooms and bedrooms before carpet gripper rods were invented in 1939, as before wall-to-wall carpet, lino was best for keeping draughty rooms warm.

And despite the brand’s tongue-twisting title, by the time the Second World War rolled around, linoleum was a household name.

In fact, long before the likes of Hoovers and Jacuzzis, it was the first brand name which became the generic name for the product itself.

But anyone born and bred in Fife will be more familiar than most, with the “queer-like smell” of oxidised linseed oil from the linoleum factories – immortalised in a poem by Mary Campbell Smith – earning Kirkcaldy the reputation of ‘the town that floored the world’.

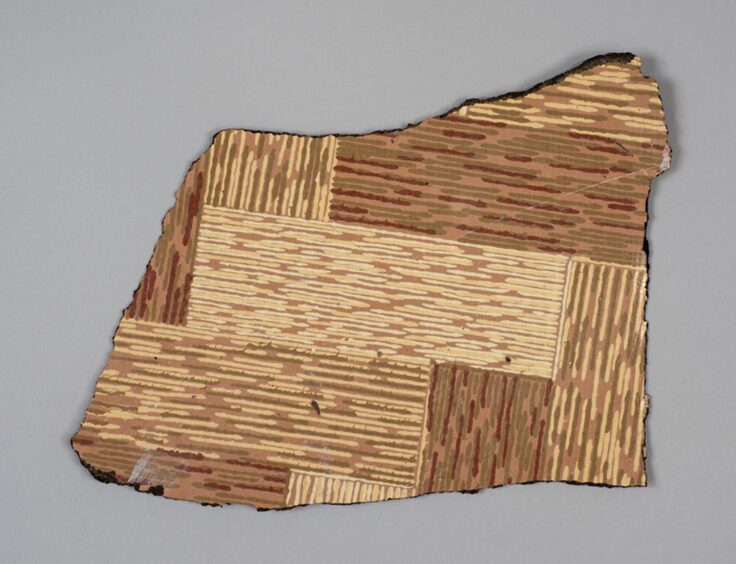

Now, with help from Forbo, Kirkcaldy Galleries are presenting an exhibition exploring the linoleum industry in Kirkcaldy and wider Fife, boasting standout objects such as a lino tile designed by the acclaimed William Morris, and a scrap of wood-effect linoleum from the childhood home of none other than Sir Paul McCartney.

“The floor covering industry in Fife started in Kirkcaldy in 1847, with Michael Nairn and Co,” explains exhibition curator Lily Barnes, who hails from Essex but has made a home in Fife.

“When Nairn’s was already going as a canvas manufacturer, they realised there weren’t any Scottish floorcloth firms, so if they got in there first they could get ahead of the market.

“Then when Frederick Walton’s patent ran out, Nairn’s had 20-30 years of manufacturing experience under their belts, so they were primed to become the first linoleum manufacturers in Scotland.

“From there, two more factories – the Tayside Floorcloth Company and the St John’s Works – sprang up in Newburgh and in Falkland, in 1891 and 1893 respectively, which we’ve showcased through this project.”

Were you a Nairn’s family, or a Barry’s family?

Over the following decades, several more firms sprouted in Kirkcaldy, and Lily reveals that by the start of the First World “one in four people in the town were working in linoleum”.

Several of those smaller firms came together to form conglomerate Barry, Ostlere and Shepherd, known commonly as Barry’s, which was the main competitor of Nairn’s until the 1960s.

And for Lily, a highlight of putting the exhibition was seeing just how strong the ties are between Kirkcaldy’s lino factories and its people.

“Whenever I mentioned it to anyone in Fife, especially Kirkcaldy, they knew exactly what I was talking about,” smiles Lily, who interviewed former factory workers as part of an oral history project around the exhibition.

“And they could take turns telling you when this factory opened, whether they were a Barry’s family or a Nairn’s family, and exactly what all of their relatives did in the factory going back generations.

“In that sense, even though a lot of the buildings are gone and linoleum isn’t so common now, it really has left its mark in the consciousness of the people who live in Kirkcaldy and across Fife.”

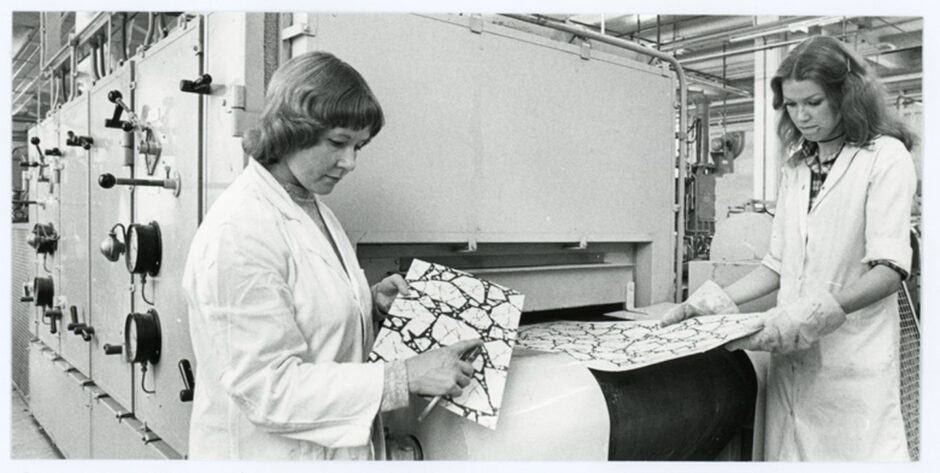

One of the things that made Kirkcaldy’s lino manufacturing plants unique was the abundance of women workers throughout the factories, meaning that there are entire maternal lines of female factory workers in Fife.

“We have a huge amount of families in employment here, still,” says Angus. “A lady who recently retired worked in the tile plant, and her daughter works in credit control.

“You get a lot of that even today, when jobs aren’t for life in other places.”

Women workers made Fife lino industry unique

Unlike in other areas of the UK, Fife’s factories saw women working not only in administrative and secretarial roles, but in the workshops, chemistry labs and colour-matching studios as well.

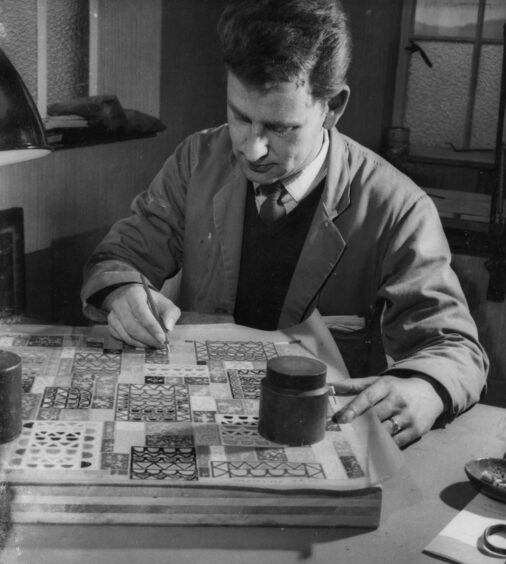

“One of the main jobs that women did in the factories was making inlaid linoleum,” explains Lily.

“With linoleum, the colour goes all the way through to the back – the pigment is in the actual material. So one of the ways you could make a design without the design wearing away would be to cut pieces of different colours and they lay them together like a mosaic.

“It’s really difficult work because all the pieces had to be cut and fit together really precisely. I think it was assumed that because women had smaller hands, they would be more dextrous for it.

“That means that this was a skilled job which was almost exclusively done by women.

“And the obviously the impact of the world wars meant that during those times, the women were working in the labs and things too.”

Expertise lives on in Kirkcaldy

Today, several historic factories which used to surround Kirkcaldy’s train station have been dismantled, with their artefacts now on show at the Kirkcaldy Galleries exhibition.

Many processes are now automated, meaning that specialisms like blockcutting and colour-matching are no longer human roles.

And with linoleum becoming less popular in home decor (“you don’t really see those bright greens or patterned borders anymore”), Forbo deals more with commercial buildings such as hospitals, schools, GP surgeries and office spaces than domestic dwellings.

But Angus insists that under the banner of Forbo, Fife’s flooring industry is as solid and stable as ever – and is still cornering the market in terms of both equipment and expertise.

“The reason it’s relatively unique here is it would cost a huge amount of money to build a plant from scratch,” the Orkney native explains.

“Everything’s bespoke, and that’s one of the reasons why the people locally are so important.

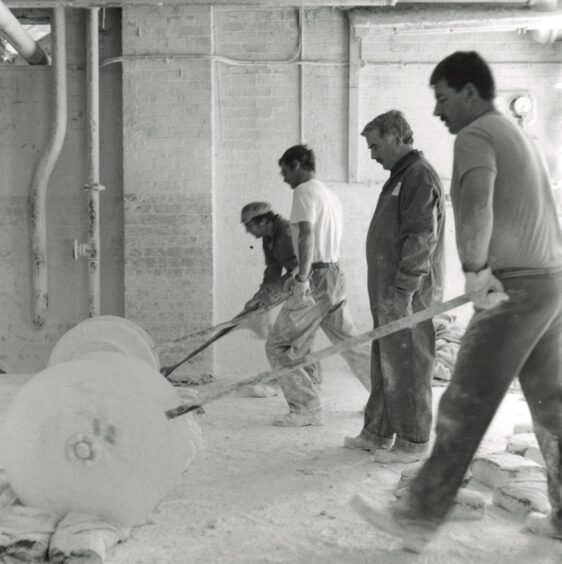

“There’s obviously quite a bit of advanced chemistry in lino manufacture, but it’s rather like the whisky industry in that you’re dealing with variable natural raw materials. So the guys on the plant are mixing chemistry and skills.

“There’s 100% a collective expertise in the local area because of that.”

‘Net-zero’ making lino cool again

And it’s the very ingredients of linoleum – all the way back to that story of linseed oil and paint drying – which Angus believes are key to paving the way to the future of Fife’s flooring industry.

While it was muscled out by vinyl in the late 20th Century over the small matter of being flammable (also the reason it wasn’t used on battleships after Pearl Harbour) linoleum’s bio-based nature means it is one of the world’s most sustainable floor coverings – albeit “accidentally”.

“The product wasn’t invented to be sustainable, right?” smiles Angus.

“It was invented to be a good floor covering. But the reality is, some of its properties have really recaptured people’s imaginations because it is sustainable.

“We measure cradle-to-gate, which is everything that happens before the factory and in the factory. On that measure, we’re actually reducing 400g of CO2 in the atmosphere with every square metre we produce.

“We’re effectively climate-positive, so we really help people with net-zero. And you comfortably get 25 years out of a floor.

“That particularly appeals when we’re dealing with architects and interior designers looking at the challenge of designing net-zero buildings. So we’re very much still here.”

Now, linoleum from Forbo’s Fife factory ships all over the globe, and its sustainable nature means the future is bright for the town that floored the world.

Indeed, when it comes to the challenge of tackling net-zero, it seems the answer was squeaking under our feet all along.

Flooring The World, an exhibition about linoleum, is free to see at Kirkcaldy Galleries until February 25 2024.

Conversation