It’s summer in St Andrews and the seats are up at the 18th hole for the 150th Open Championship.

But could the very car park I’m standing on, and the neighbouring Himalayas putting ground…

…be underwater by the end of the century?

In future decades, the sea is predicted to creep in.

The Old Course might be relatively safe for now…

…but erosion and sea level rise threaten the historic links.

And if the predictions are correct…

St Andrews Links clubhouse will be surrounded by a moat by 2100.

With so much uncertainty surrounding our climate, will the Old Course be around for the 200th Open Championship?

“I’m pretty confident it will be,” says Ranald Strachan.

“I’ve never seen an organisation that’s as much on the front foot as the Links Trust.”

We found out how St Andrews Links Trust plans to “hold the line” and preserve the historic tees and fairways at the Home of Golf.

Ranald Strachan is environmental development officer for St Andrews Links Trust.

He has been involved in work to protect the precious golf courses just yards from West Sands.

How do you protect St Andrews’ iconic features from flooding?

Ranald says sand dunes hold the key to protecting the Trust’s valuable assets.

Rather than build ugly rock armour, this ‘soft’ form of coastal defence is increasingly seen as the go-to option for saving Scotland’s shorelines.

“It’s a really positive thing. We’ve got huge public support for doing it and I think that shows.”

In addition to looking pretty, the dunes provide a habitat for wildlife.

And they can regenerate.

“All you can do is follow best practice.

“There’s an understanding that things could go wrong. The dunes could be hit by a storm surge and we’ve lost it.

“That’s their worth. They can and will recover.”

Sand dunes are first line of defence from the sea

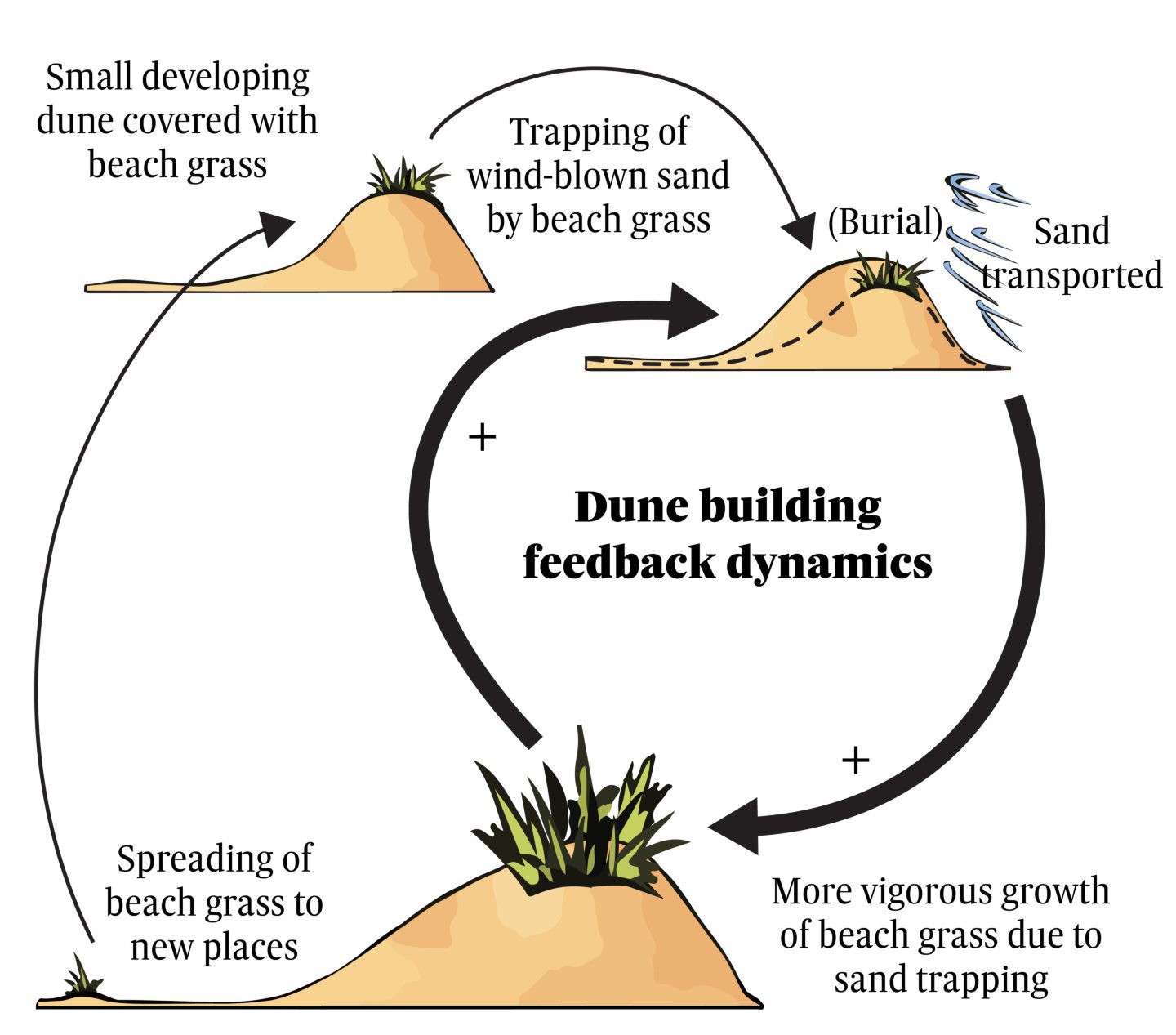

Dunes are natural features. But they sometimes need a bit of help.

Doing this is “pretty simple really” says Ranald.

“You just get a lot of diggers.

“You put the diggers out at the lowest tide then harvest sand.

“Dumper trucks dump it and then a digger at the other end sculpts it to look like natural dunes.”

Wobbly fencing is put up – designed to be difficult for people to jump over as well as to trap sand.

Then beach grasses – marram and lyme – are planted to stabilise the dunes.

Despite thousands of people using the beach, Ranald says most members of the public respectfully keep off the dunes.

Why doing nothing is not an option

St Andrews Links Trust has been working with the Dynamic Coast project.

Using Dynamic Coast data, we have made our own visualisations of how our local coasts could look in the future.

It should be noted that these are our own interpretations of the Dynamic Coast webmaps.

Sandy Reid is director of greenkeeping at St Andrews Links.

He describes the coastal predictions drawn up by Dynamic Coast as “alarming”.

However he adds: “But that’s a do nothing scenario.

“We’re not doing nothing.

“We’ve got a track record of doing good work and we’re making gains.

“I would say I’m confident that we can hold the line.”

To do nothing would see the Jubilee Course’s 8th and 10th holes threatened in the next 20 years.

But Sandy says it is not just about bolstering flood defences.

The wider world has to act on climate change.

“The Dynamic Coast projections are very much a do nothing scenario – us doing nothing and the wider world doing nothing about climate change.”

Credits

Words and interviews by Aileen Robertson

Visualisations by Chris Donnan

Graphics by Gemma Day

Scrollytelling by Emma Morrice, Joely Santa Cruz and Lesley-Anne Kelly

SEO by Jamie Cameron

Drone photography by Steve Brown

Photography by Kim Cessford

Special thanks to Dynamic Coast.

Conversation