For a small country, Scotland has huge variety in terms of scenery – mountains, beaches, glens and lochs – making it a dream destination for tourists.

Yet all these areas have one thing in common – the sign displayed in the window of every bar, café and shop saying simply ‘Staff wanted’.

This is partly due to Brexit – surely the greatest act of political self-harm that a country has inflicted on itself – which saw thousands of European workers pack up and leave.

But any staffing crisis can surely also be blamed on the pay offered by the retail and hospitality industries in this country, where the minimum wage is often hard to differentiate from slave labour.

We’re now back to treating these people like dirt, and expecting them to be polite to us as we do so.

-Marie Penman

Bosses of multi-million pound companies are often heard to remark that people in this country are too lazy/workshy to fill their many job vacancies. A major employer in the US thought the same, until a recruitment agency suggested they bump up the wage offered, by $5 an hour. Suddenly, the company was flooded with applications.

It’s not that people don’t want to work – it’s that they don’t want to work for slave wages.

The minimum wage is set by the UK government, decided on by politicians who have very probably never worked for the minimum wage in their lives.

It’s officially accepted that this amount is not enough to live on – we know that, because there is an alternative offered, called the Living Wage, which businesses can choose to sign up for, but sadly, rarely do.

In the meantime, young people, women (more so than men) and others commit to jobs in the service industry that involve working very hard for very little money.

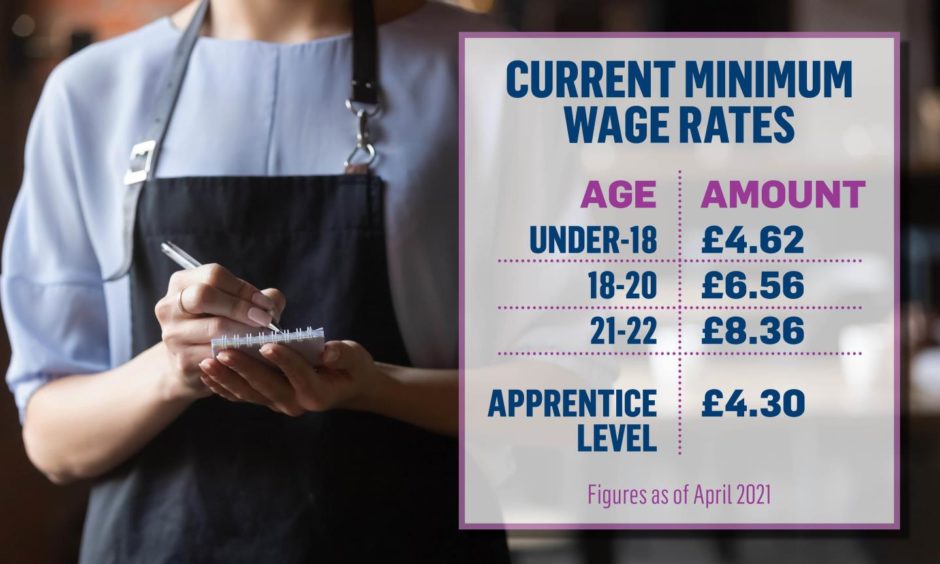

So just how low is the minimum wage?

Current rates show that if you’re under-18, as many in retail or hospitality are, you will be paid the princely sum of £4.62 an hour.

Aged 18-20, and your pay jumps to £6.56 an hour.

Once you reach the wisdom and maturity of 21-22, you are rewarded with £8.36 an hour.

Think how long you’d have to work on those wages to earn enough to feed and clothe yourself. Then think about how much the average monthly rent costs.

And take into account the fact that many people in these industries are working on zero-hour contracts, meaning they aren’t guaranteed a set number of hours – it could be 40 hours one week, four the next.

It doesn’t seem like a great deal, and that’s before we even look at what these staff have to put up with in the workplace. Apart from the early starts, late finishes, lack of fixed breaks and bullying bosses (who’d work in a top-class restaurant run by a ‘celebrity’ chef these days?), service workers have to deal, on a daily basis, with the great British public.

Remember during lockdown, when everyone put up supportive notices and clapped on the streets for key workers? It appears that any brief display of kindness and solidarity towards shop staff and hospitality workers has long since gone.

We’re now back to treating these people like dirt, and expecting them to be polite to us as we do so.

One of my sons works as a barista for a large chain of coffee shops, on the minimum wage. He is routinely shouted at and insulted by customers who put in written complaints (seriously) if he forgets to add the flavoured syrup they requested or uses the wrong kind of milk.

As my son remarked, exhausted after another 10-hour shift when he hadn’t even had time to eat lunch, ‘When did people start getting so angry about coffee?’.

I spent a few days driving around the Highlands last week, admiring the scenery and noticing how every single business seemed to be short-staffed. One evening, sitting in a pub having a quiet drink, I watched the two female staff on duty cope with the demands of their jobs.

‘I was dismayed by what I saw’

The place was packed, full of sunburned, middle-aged drunks, and as one young woman worked behind the bar, making up the drinks, the other weaved her way through the crowds, taking orders via a tablet, mopping up spilled drinks, clearing away empty glasses and avoiding the reaching hands and suggestive comments of the mainly male clientele.

I was dismayed by what I saw – the way she was treated, the way customers behaved, and the way she just accepted this as her job and continued working away, quietly and efficiently.

I observed her for about 20 minutes in total, and calculated that as a teenager – she looked about 18 – she had probably earned the grand sum of £2.15 in that time, doing the kind of stressful, repetitive, physically exhausting work that most of us wouldn’t do for five times that amount.

With the heavy industries like coal, steel and shipbuilding long gone, the retail and service industries in Scotland are now two of its biggest employers. Hundreds of thousands in this country currently work for the minimum wage.

Is that really what we think they are worth?

And if so, it’s no wonder that many of us fail to value the poor – quite literally – people who have no choice but to work in these industries.

Marie Penman is a journalist and former lecturer in journalism at Fife College.