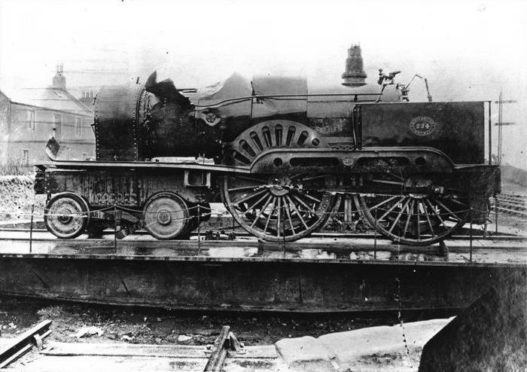

It was the unlucky engine which plunged twice into the icy waters of the River Tay.

North British Railway (NRB) Engine 224 took 75 people to their doom on the Tay Bridge in 1879 but was eventually fished out of the watery bed 140 years ago in April 1880.

The engine, which was built by Thomas Wheatley at Cowlairs Works in Glasgow in 1871, was spare in Dundee when it was called out to work a mail train to Burntisland after the regular engine from Ladybank failed.

It did so without incident on the southbound run before working the 5.20pm northbound service later in the day which was due to arrive at Dundee just before 7.30pm.

Wind pulled down the iron girders

The weather was exceptionally bad that night and the high tower at Kilchurn Castle on Loch Awe also fell and many houses in Scotland lost their roofs.

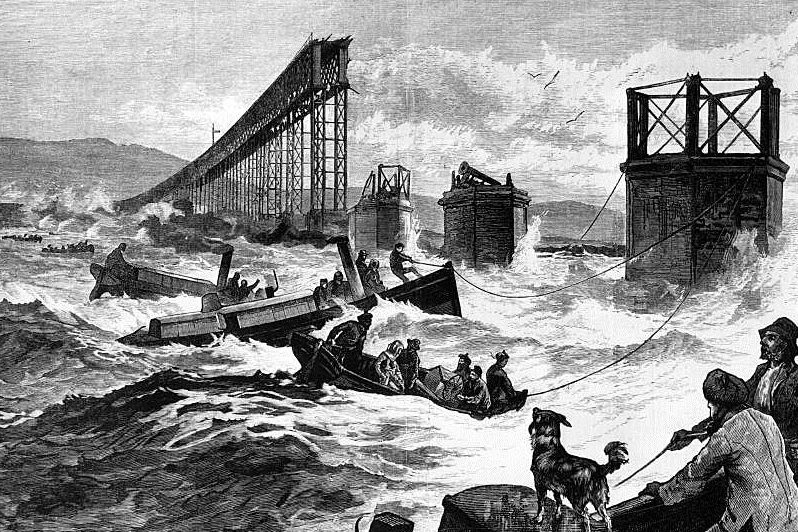

Shortly after 7.13pm the Tay Bridge collapsed when the wind pulled down the iron girders in the central section away like matchwood.

The driver, David Mitchell and fireman John Marshall had no warning and neither closed the regulator nor applied the brakes.

Engine 224 tumbled into the river below but she was protected by the bridge girders which formed a cage around the train as they fell together.

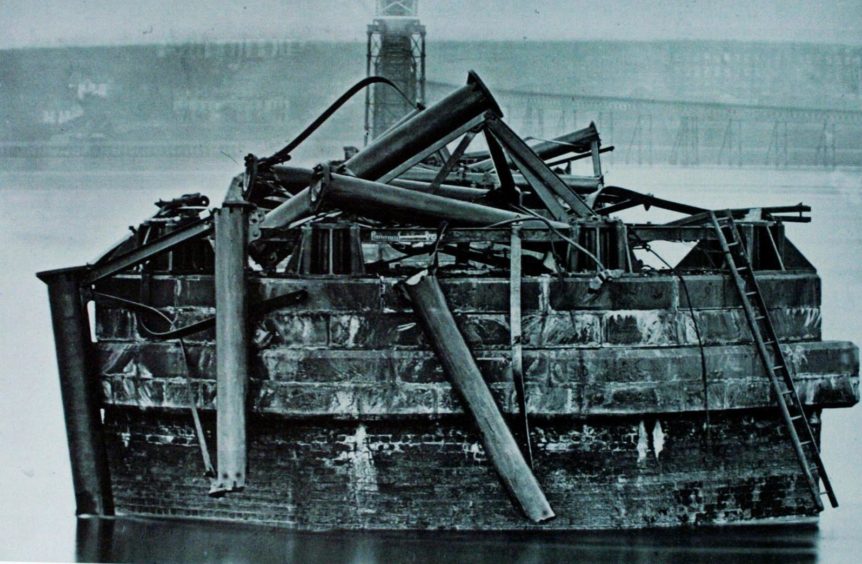

The first attempt to recover the stricken engine in April 1880 failed when the chains broke.

Two days later a second attempt raised her from the bed of the river where it was towed to the landing stage at Tayport.

But the engine overbalanced and the tow broke which sent it back to the bottom of the sea bed.

A week later the engine was finally brought to the surface.

It was put on the rails at Tayport.

Emotional journey to Cowlairs

That meant that after months of hard work at the disaster scene, all the carriages and engine which had formed the ill-fated train, were now recovered.

Robert Marshall was the first person to drive Engine 224 at Tayport when she travelled under her own wheels to Cowlairs for repairs.

It must have been an incredibly emotional moment for Mr Marshall whose brother John had been the fireman on the fateful night.

The engine itself gained the nickname ‘The Diver’ as a result of its accident and its difficult recovery.

Engine 224 eventually returned to traffic and was placed on the line between Edinburgh and Glasgow in August 1880.

A large crowd were in Edinburgh to catch a glimpse of the engine when it arrived for the first time.

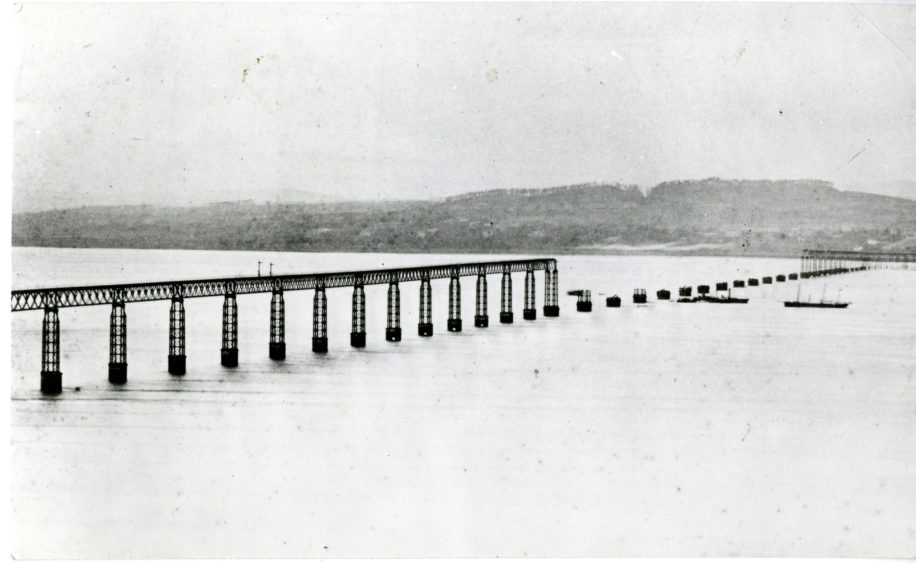

After the disaster both the North British Railway and supporters of the Tay Bridge were determined that it should be rebuilt.

The new Tay Bridge took five years to build and was opened without ceremony in 1887 while The Diver continued to be in service in Scotland.

Bad omen

Train drivers became reluctant to take the train across the new Tay Bridge believing it to be unlucky or a bad omen.

However, on the 29th anniversary of the disaster, the engine was used to serve the exact same route, making the crossing to Dundee across the new Tay Bridge.

The driver gazed down at the stumps of the old bridge still protruding from the Tay and reflected on the unimaginable events of 1879.

In 1913 the engine was now working regularly on the Berwickshire line from Berwick to St Boswells and was also used from time to time on various branches including Riccarton and Newcastle.

It would also pull goods trains at Possilpark and Maryhill in Glasgow and remained in service until 1919.

She was finally sold to a Glasgow scrap yard.

A station house at Dalhousie at the west side of the line once featured a letterbox made from metal recovered from The Diver which was perhaps ironic given her cargo when she plunged in 1879 included six bags of never-to-be-delivered letters.

The letterbox is now in a museum in Bellingham.

Derailment theory

Tayside rail enthusiast John Ruddy said: “Although Victorian railwaymen were a superstitious bunch, the nickname they gave to Engine 224 after the disaster perhaps indicates that they had their own ideas as to why the bridge collapsed.

“The bridge’s designer, Sir Thomas Bouch, had theorised that the locomotive had derailed, and by crashing into the sides of the girders, had caused them to collapse.

“The drivers and firemen who had driven over the bridge may well have felt this was possible, if as reported, there was a kink in the rails leading to the high girders.

“The subsequent inquiry thought otherwise, but who knew the old bridge better than they?”

The number plate from the tender of 224 has been preserved at Selkirk Museum.

Marvel of Victorian engineering

When the Tay Bridge was completed in 1878 after taking six years to build, it was one of the longest bridges in the world.

Famous visitors including the Emperor of Brazil, Prince Leopold of the Belgians and Queen Victoria herself came to pay homage to this marvel of Victorian engineering.

It was during a violent storm in the winter of 1879 that the unthinkable happened.

The storm was recorded on board the Mars training ship lying near Newport as being force 10 or 11.

A Northern British Railway steam locomotive plunged into the Firth of Tay when the rail bridge beneath it collapsed on December 28.

The train, which had been travelling from Edinburgh to Dundee, took all of its passengers with it.

Death toll

The death toll from the Tay Rail Bridge disaster has never been confirmed.

The bridge had only been open for about 18 months.

Designed by Sir Thomas Bouch, it was six years in the building, constructed by 600 men and costing £300,000.

The names of the 59 people known to have died in the tragedy are listed on memorials at Wormit and Dundee Riverside which were erected in 2013.

The driver of Engine 224 who died with fireman John Marshall was David Mitchell.

His body wasn’t found until nine weeks later.

Woken by a nightmare

His family said David had been woken by a nightmare the night before the accident, a nightmare in which his locomotive was falling.

David’s watch was recovered from his body, given to family and it was still in perfect working order 100 years later.

The watch owned by the train’s guard, David McBeath, had, however, stopped at precisely 7.17pm, which times the accident to the last moment.

The Board of Inquiry concluded that a combination of design failures, construction and maintenance were at fault, with renowned engineer Sir Thomas officially blamed.

Montrose bridge defects

Sir Thomas could have been responsible for a similar catastrophe in Montrose.

The South Esk Viaduct near Montrose was also designed by Sir Thomas while he was working for the North British Railway.

Due to delays in building the Tay Bridge and the line by Dundee, it was not built until 1879.

Following the Tay Bridge disaster of 1879 the viaduct was inspected and found to have a distinct curve, although the plans showed a straight bridge, and many of the piers were out of perpendicular.

Tests in 1880 over a period of 36 hours using both dead and rolling loads led to the structure becoming seriously distorted and eight of the piers were declared unsafe.

The bridge was demolished and work started to rebuild it in 1881 to a design by William Galbraith before the line eventually opened to passenger traffic in 1883.

The replacement was also of wrought iron lattice girder construction based on designs dating back to the 1830s and the viaduct at Montrose was probably the last major bridge in the UK to be built with this type of bracing.