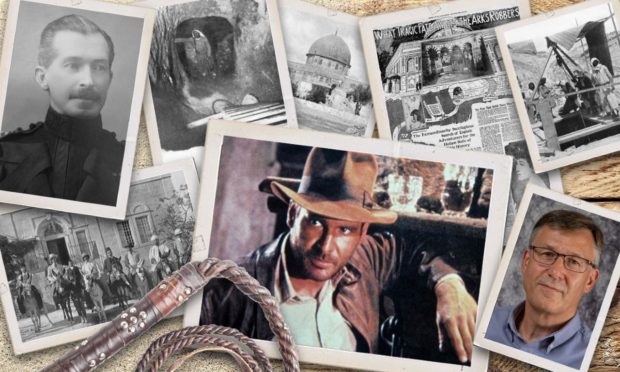

Most of us have seen Harrison Ford cracking his whip, performing death-defying stunts and defeating dastardly Nazis in Raiders of the Lost Ark.

Steven Spielberg devised the blockbuster 1981 film as a breathless roller-coaster ride and it was the start of a movie franchise which is still going strong.

But, long before the director called “Action”, a group of real-life adventurers embarked on their own quest for the ancient Ark of the Covenant which began when a Finnish poet and biblical scholar, Valter Juvelius, convinced an English aristocrat, the Honourable Montagu Parker, that he had found hidden cyphers in the Old Testament.

It’s like Downton Abbey meets Dan Jones

Together, they created a syndicate and raised the equivalent of more than £1m, much of it from wealthy investors with Scottish roots.

They embarked on an expedition which featured secret codes, bribery, betrayal, gun-running, a crystal ball-gazing Swiss psychic, bankruptcy and an eventual riot in Palestine after the Britons and their colleagues were accused of stealing priceless religious items.

Scottish writer Graham Addison has investigated their exploits and created a compelling account of a hidden chapter from the early 20th century.

As he said: “It sounds improbable: Downton Abbey meets Indiana Jones meets Dan Brown.” But it all happened and, as you might expect, it didn’t end well.

The main financiers of the expedition were the Wilson family who made their money in Australia, but whose roots were originally in Scotland and Ireland.

Sir Samuel Wilson and Lady Jean Wilson, nee Campbell, were the parents of Clarence and Gordon Wilson who went on the expedition, which set off in August 1909.

Lady Jean’s father had been born in Aberfoyle in Perthshire, as the prelude to emigrating to Australia, where he was credited with being the first person to find gold in Clunes in Victoria which sparked the sprawling Australian goldrush in the 1850s.

Robin Duff, who also joined the expedition, was a relative of the Duke of Fife and his grandfather Robert George Duff was born in Turriff in Aberdeenshire.

It was a motley crew of privileged well-to-do gentlemen who set off in August 1909 in search of the Ark, the most potent and precious object of the Jewish faith.

In the Bible, Moses had constructed it to hold the tablets recording the Ten Commandments which God had given to him on Mount Sinai.

Nobody, even in the Middle East, actually knew if the Ark existed or was just a piece of scriptural mythology or where it was located, but Parker and his group of young, largely Eton-educated Britons were convinced they could solve the mystery.

Parker claimed he had found treasure

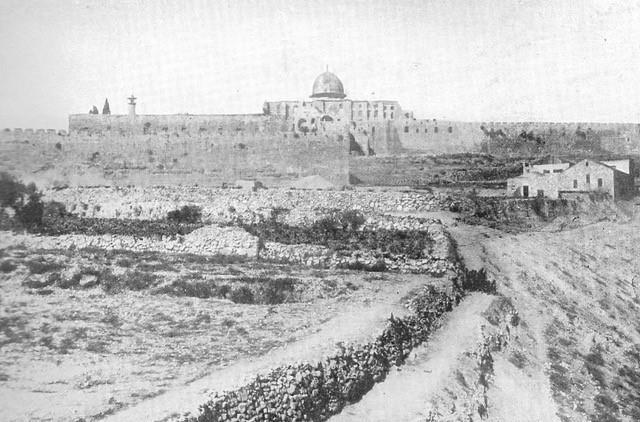

Yet, before they could start digging in Jerusalem, they needed permission from the Ottoman government and this is where matters quickly grew murky.

Parker sent a letter to the Ottoman finance minister, signing himself as a Grenadier Guards officer, resident at the Turf Club in Piccadilly in London and wrote: “I believe I have discovered a very important treasure in the Ottoman Empire.”

He had no doubt that he and his colleagues were about to make history. They certainly made headlines around the world, though not for the reasons they would have wanted.

Mr Addison’s new book, Raiders of the Hidden Ark, records how the men, including Parker, the Wilsons and Duff, were intrigued by the work of the inscrutable Juvelius, who kept unearthing what he regarded as new codes and arcane cyphers.

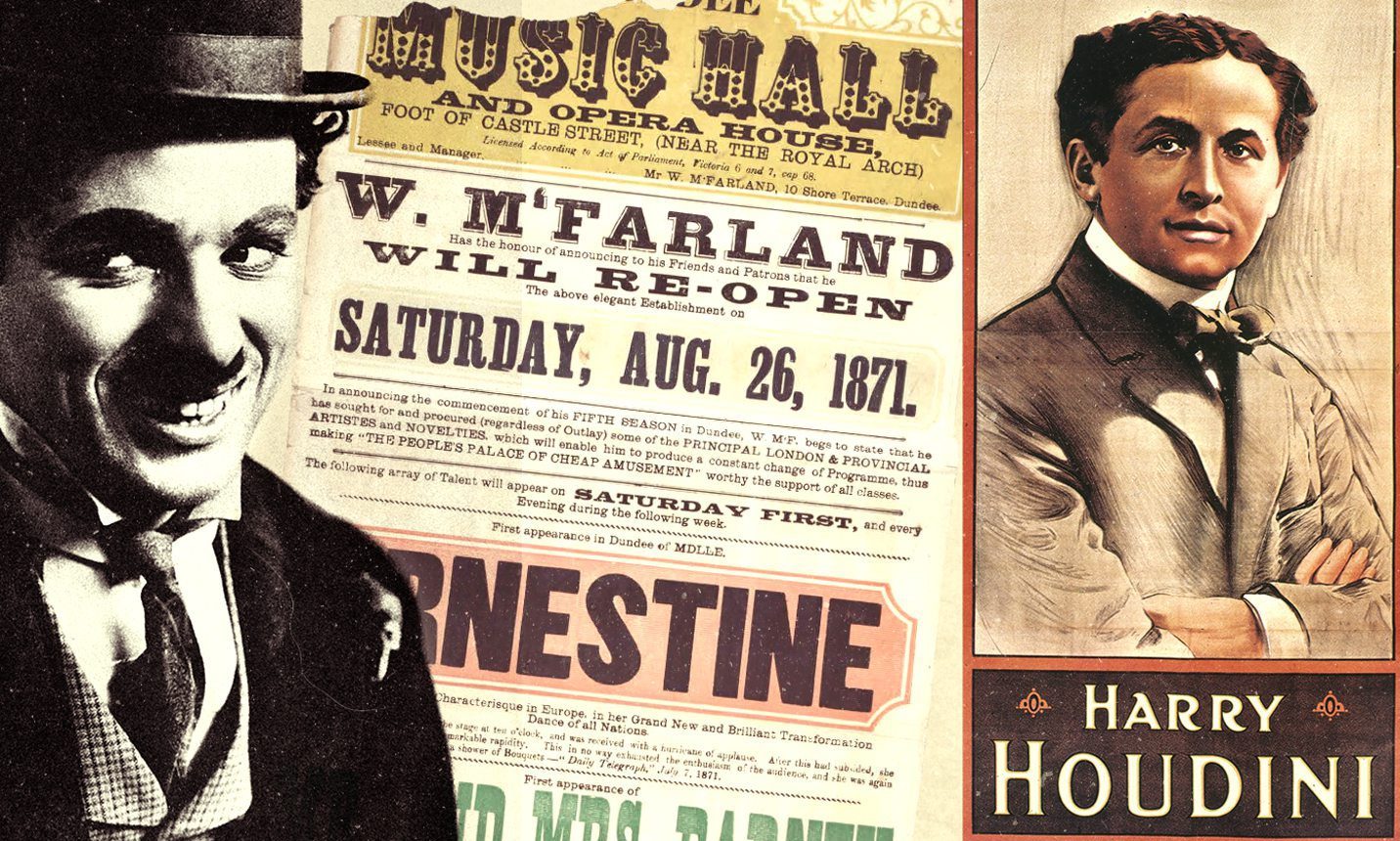

His methods may sound fanciful or even absurd nowadays, but the expedition took place in an age where men such as Sherlock Holmes author Sir Arthur Conan Doyle could proclaim his belief in fairies and spiritualism and be taken seriously.

And this was also a time where readers devoured coverage of such stories as the construction of the Titanic, the polar missions of Robert Falcon Scott and Ernest Shackleton and various attempts by aviators to travel further than ever before.

Given the instability of the Ottoman regime, Parker was forced to negotiate with a succession of prime ministers and other officials in Constantinople.

But, as the book relates: “He secured unprecedented cooperation from the Ottoman Empire, probably helped by some generous bribery along the way.

“The expedition and its members were allowed to dig, protected and enabled by the Ottoman authorities, with whom they would share the proceeds of the treasure and they dug in Jerusalem for three years.

“But then, in 1911, they had to flee for their lives on the same yacht they arrived on, having dramatically upset the religious tinderbox that was Jerusalem.

“The uproar caused the Ottoman authorities to sack and imprison officials involved in aiding the expedition and institute a major inquiry to determine what had happened.”

In April 1911, they bribed the guardian of the Haram al-Sharif [temple] to let them dig in the Dome of the Rock. But they were discovered, their conduct was immediately described as sacrilegious and blasphemous and riots and disorder broke out.

The disastrous conclusion to the mission and the ensuing mayhem were the stuff of dreams for the world’s media and everybody from the New York Times – “Have Englishmen Found the Ark of the Covenant?” – to Vossiche Zeitung – “Theft of Relics in the Jerusalem Mosque of Omar” – covered the story in great detail.

The Aberdeen Journal carried no less than nine different accounts, including one headlined “Sacrilege in Holy City: Charges Against British Party.”

This reported: “The members of the expedition had declared that they expected to find a manuscript which would set at rest all doubts as to the Resurrection of Christ.

“But their undertaking was exceedingly adventurous, as if it had been for a moment thought that they intended to remove treasure or manuscripts from the Holy Rock, they would have run the imminent risk of being strangled by their own workmen.”

In the event, the Britons escaped by the skin of their teeth – and through the assistance of some of the Ottoman authorities with whom they had been negotiating – but there was no happy ending for several of the participants in the ill-fated scheme.

As Mr Addison said: “Within a few years, three were dead, one was mad, two were bankrupt, one was divorced and another was deported.”

The Jewish Chronicle had declared: “Any unauthorised person who attempted to disclose the secret chamber containing the Ark would be cursed ‘sixty and six fold’.

An exaggeration, perhaps, but there was no reward for these adventurers.

The book sheds light on a largely untold episode which took place at a pivotal time in European and Middle Eastern history, shortly before the First World War.

And Mr Addison explained why the incident had captured his attention.

He said: “I read Simon Sebag Montefiore’s excellent biography of Jerusalem and it includes a handful of pages about a bizarre expedition of young Eton-educated men who went searching for the Ark of the Covenant which was based on secret cyphers supposedly found in the Bible.

“When I tried to find out more, I discovered that there was not much more about the expedition and much was inaccurate. So I decided to try and tell the whole story.”

He added: “In doing so, I found that the situation was much more complex than first portrayed. For example, these Eton-educated ‘English’ gentlemen turned out to have roots in Scotland, Ireland, Wales and Australia as well as England.

“I have always been interested in how the British have influenced so many different parts of the world. There are few places on the planet where the British have not left some imprint, and Jerusalem and the Holy Land certainly do not fall in that category. The Parker expedition certainly left a mark on Jerusalem.

A link between Parker and the author

“I also discovered that my grandfather and the Honourable Montagu Brownlow Parker, both served in Gallipoli and Egypt during the First World War.

“It is unlikely that they ever met; Monty was an English Grenadier Guards officer and the son of an earl [who lived in luxury until his death in 1962].

“My grandfather was a corporal who had worked on the railways in Scotland and was the son of a tailor from Aboyne.

“However, who knows, maybe my grandfather did bump into Monty in Alexandria or Port Said a century ago!”

Mystery continues to surround the existence or otherwise of the Ark, despite the fact it hasn’t been seen for more than two and a half thousand years.

And, as Mr Addison discovered during his research into the subject, a grisly fate often befell those who interfered in the saga.

He said: “In 1930, the New York Times carried a letter, signed M.E.L.F. It told of a ‘Scotch’ woman who lived in Jerusalem and the letter said she possessed the power of foresight. She reportedly had a vision of the Ark’s exact location – it was ‘in a small chamber underground at a certain spot in the temple area.”

“The woman worked for the American School of Archaeology, but unfortunately, before she could tell many people, she was murdered and her body was found hidden in her house near the Garden Tomb a few weeks later.”

Perhaps, when it comes to religious artefacts, it is wisest to leave the past in the past.

Raiders of the Hidden Ark is published by Edgcumbe Press.