Michael Alexander previews an online Dundee lecture which examines the forgotten role of two doctors who helped save the lives of frostbitten crew while marooned for months on a remote Antarctic island.

It is regarded as one of the most incredible survival stories of all time.

Ten years after Sir Ernest Shackleton served as third officer with Captain Robert Falcon Scott during the Dundee-built Discovery’s successful British National Antarctic Expedition of 1901-04, and three years after Scott perished returning from defeat to Amundsen at the South Pole in 1912, Sir Ernest Shackleton found himself at the centre of his own life and death expedition.

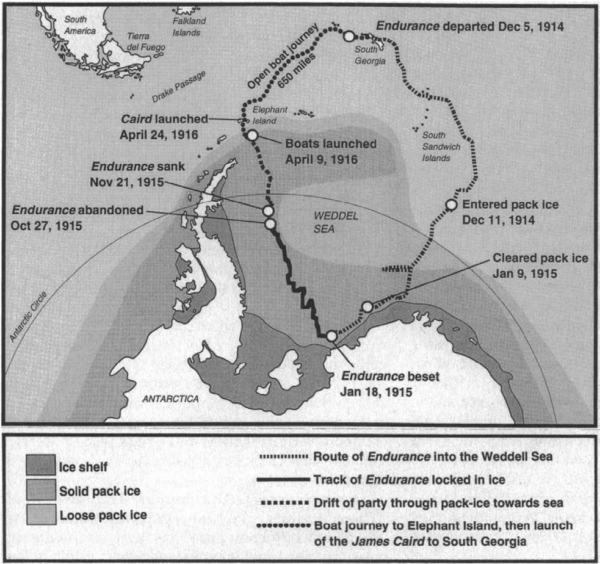

The intention of Sir Ernest Shackleton’s Imperial Trans-Antarctica expedition of 1914 – 1917 was to make the first land crossing of Antarctica from the Weddell Sea via the South Pole to the Ross Sea.

However, in 1915, Shackleton’s ship the Endurance became trapped in dense pack ice and the 28 man crew had no choice but to abandon the Norwegian-built ship before she sank into the icy depths.

After months spent in makeshift camps, they embarked upon the treacherous journey across the pack ice toward land, hauling their lifeboats by hand where possible, and eventually landed on the desolate and uninhabited Elephant Island, hundreds of miles from mainland civilisation.

Shackleton and five others then made an 800-mile (1,300 km) open-boat journey in the seven metre long James Caird – named after one of Dundee’s wealthiest jute barons – to reach South Georgia.

From there, Shackleton was eventually able to mount a quite incredible rescue of the men waiting on Elephant Island and bring them home without loss of life.

But while this classic tale of leadership and heroism is remembered as a feat of navigation, endurance and incredible bravery, less is spoken about the role of two doctors – including Dundee doctor Alexander Macklin – who battled the odds and the Antarctic winter to keep the party alive while they awaited rescue on Elephant Island.

Those heroic efforts will be the focus of a free online public lecture called Shackleton’s Antarctic Doctors, taking place on Monday September 28 and organised by Lifelong Learning Dundee – a not-for-profit organisation of volunteers providing general interest classes based at Dundee University.

Chaired by John Rowan, the talk is by Dr Paul Firth, a paediatric anaesthetist at the Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, USA and an Assistant Professor at Harvard University.

He previously worked at Ninewells Hospital, Dundee.

Dr Firth has climbed extensively in the Himalayas, the Andes, Alaska and East Africa.

His academic interests include anaesthesia, high altitude medicine and Antarctic history.

The lecture, which has also made contact with a descendent of one of the doctors, will examine medical practice on Elephant Island which ultimately helped to keep the awaiting crew alive at a time when they didn’t know if they’d ever be rescued.

“Although Ernest Shackleton’s Endurance Antarctic expedition of 1914 to 1916 is a famous epic of survival, the medical achievements of the two expedition doctors have received little formal examination,” said Dr Firth, who recalled how the ship’s carpenter ‘Chippy’ McNish wrote: “I don’t think there will be many survivors” as he left with Shackleton to search for help.

“Marooned on a gale-lashed, ice-bound island, with no communication with the outside world, Shackleton’s two doctors had to improvise the medical care required to manage the consequences of exposure to the extreme polar elements.

“Most remarkable, perhaps, was the challenge of delivering an inhalational anaesthetic, using a dangerous and frequently lethal volatile anaesthetic agent, in the penumbral depths of an austral winter.”

Dr Firth explained how Melrose-born Manchester University graduate Dr Alexander Macklin, who set up practice in Dundee from 1926, and Northern Ireland-born Birmingham University graduate James McIlroy, administered a chloroform anaesthetic to 22-year-old crew member Perce Blackborow.

During the trip in the lifeboats, he had suffered severe frostbite to his feet.

As the weeks on the island passed, it became clear that the toes of his left foot were necrotic.

By June, given the risks of infection and gangrene, the doctors decided that the dead digits would have to be excised.

“As the saturated vapour pressure of chloroform at 0°C is 71.5 mmHg and the minimum alveolar concentration is 0.5% of sea-level atmospheric pressure (3.8 mmHg), it would have been feasible to induce anaesthesia at a low temperature,” said Dr Firth.

“However, given the potentially lethal hazards of a light chloroform anaesthetic, an adequate and constant depth of anaesthesia was essential.

“The pharmacokinetics of the volatile anaesthetic, administered via the open-drop technique in the frigid environment, would have been unfamiliar to the occasional anaesthetist.

“To facilitate vaporization of the chloroform, the team burned penguin skins and seal blubber under overturned lifeboats to increase the ambient temperature from −0.5° to 26.6°C.

“Chloroform degrades with heat to chlorine and phosgene, but build-up of these poisonous gases did not occur due to venting of the confined space by the stove chimney.

“The anaesthetic went well, and the patient—and all the ship’s crew—survived to return home.”

Dr Firth said that some 100 years after the voyage, the Endurance continues to fascinate and educate.

Dental pain, a common complication on prolonged expeditions, was another problem the doctors had to deal with – carrying out extractions without anaesthetic.

“Perhaps the interest in these tales endures,” he added, “because we recognize in these stories those fundamentals sometimes overlooked in the cluttered press of daily life and medical careers.

“In an existence reduced to the most basic of elements, removed and remote from the rest of humankind, the struggles of this small band of men illuminate the meaning of companionship, cooperation, and selfless dedication to others.”

*Shackleton’s Antarctic Doctors, organised by Lifelong Learning Dundee, takes place online on Monday September 28 at 6pm. To book a free place, go to www.eventbrite.co.uk/e/lld-free-public-lecture-shackletons-antarctic-doctors-monday-28th-sept-tickets-119976985393