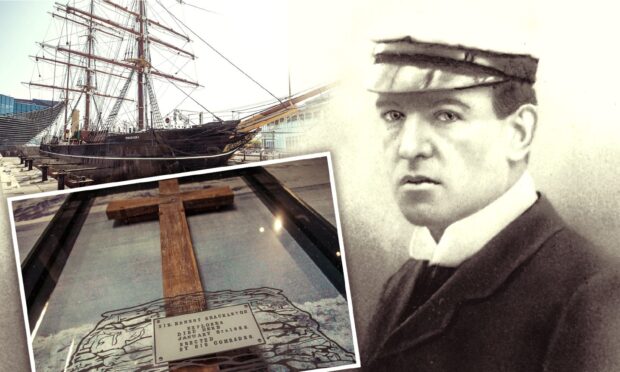

More than 170 years since Sir John Franklin embarked on a doomed expedition to discover the fabled Northwest Passage, melting ice is opening up the Canadian Arctic to tourists. Sarah Marshall embarks on an intrepid voyage

A legacy is something every explorer hopes to leave behind them. But the most memorable traces of James Clark Ross’ presence at Port Leopold, on Somerset Island, are two initials and a year, 1849, carved into a rock on a bleak Arctic beach.

The letters, E and I, stand for Enterprise and Investigator, two of many ships employed in hopeless attempts to unravel the mystery of missing Royal Navy officer Sir John Franklin, who’d set out four years previously to claim the fabled Northwest Passage trade route for Britain.

It took several decades to find Franklin’s ill-fated vessels: Erebus in 2014 and, more recently, Terror, this past September.

With only a few weeks of open water each year, the search posed an enormous challenge to Parks Canada.

But fortitude, determination and a spirit of exploration have always shaped the Canadian High Arctic.

So too has ice.

Once the biggest obstacle for explorers, it’s now melting at a rate too close for comfort and opening up the area to cruise ships.

I’ve joined a voyage on the 96-passenger Ioffe, a Russian research vessel whose sister ship, the Vavilov, was involved in the mission to locate Erebus. Staff participants in the ambitious expedition proudly show off commemoration patches sewn onto their uniforms.

Completing the Northwest Passage, a shortcut between the Pacific and Atlantic Oceans, is a tightly scheduled multi-week journey, but I’ve opted for a snapshot of the cruise.

Starting in Resolute, a four-hour charter flight from Edmonton, I’ll spend seven days sailing through historic straits and a patchwork of barren islands where sheer cliffs and sweeping glaciers conceal abundant but shy wildlife.

The residents of Prince Leopold Island show no signs of retiring, though, when we visit the largest seabird colony in the Canadian Arctic.

Swooping between serrated ridges, angelic kittiwakes are starry flickers in the indigo heavens. Thick-billed murres huddle along ledges like gossiping old ladies at a bus stop, while fledglings take a tentative sea dip with guidance from their fathers. At every level, it’s ornithological mayhem.

Yet a few nautical miles away, the skies are silent.

On first impression, the Arctic appears overwhelmingly empty; shapeless plateaus are intimidating, scant vegetation is daunting, and the scale of nothingness is uncomfortably stifling.

Even the region’s apex predator is dwarfed by its surroundings.

“Bears of a monstrous bigness,” recorded by John Davis in the late 16th century, were initially mistaken by the British explorer for being sheep.

When we enter fog-shrouded Coningham Bay, buttercream dots in the distance arguably resemble fluffy balls of wool.

In reality, there’s nothing cuddly about polar bears.

Cruising in Zodiacs (inflatable dinghies) we approach downwind so the bears can’t detect our scent.

Beluga whale carcasses scatter the shale shoreline; trapped in tides, they’re hunted by both bears and Inuit indigenous people of northern Canada.

A large bullish male pulls at blubbery flesh, sniffing the air to deter any foolish hopefuls from joining his table. This is strictly a meal for one.

As the wind changes, we’re able to slowly creep within 200 metres of a mother and her yearling cub as they lovingly nuzzle and cavort in a display revealing the killer’s softer side.

In total, we clock an impressive 41 bears in just three hours – a wildlife oasis in this vast, polar desert.

It’s true: you have to work hard for sightings. Most of these animals are legally hunted by local communities and have an innate fear of humans.

At Maxwell Bay, we spend an hour circling in Zodiacs, edging ever closer to a couple of walruses rolling in the surf.

On Devon Island, at Dundas Harbour, a herd of musk ox disappears into a ravine as soon as we come ashore. A solitary male lags behind, only because he’s nursing a bleeding harpoon wound.

Inuit guide Ted conducts our stealth advance in a manner only a seasoned hunter could execute. In his pocket is a knife made from polar bear bone; it took two years to craft and dry.

“Promise me you’ll use this,” his grandfather firmly instructed as he handed the heirloom down.

For Inuit communities unable to afford expensive imports, controlled hunting is a sustainable means of survival. It’s also their connection to a cultural heritage spanning hundreds of years.

After all, they were the original Arctic explorers.

When John Rae came searching for Franklin in 1854, the Inuit were his most valuable source of information.

They spoke of white men on King William Island, and one even wore the gold braid from a naval uniform as a headband.

Startling reports of cannibalism, though, were not well received in Victorian England; Lady Franklin even tried to discredit Rae by asking Charles Dickens to pen damning pamphlets.

Although the final chapter of Franklin’s life remains inconclusive, three of his men – possibly the last survivors – were eventually found six feet under at Beechey Island.

On the day we visit, raging winds punish the land, beating shale dunes into reluctant submission. Underfoot, 450 million year-old coral fossils are evidence these tectonic plates were once at the Equator. Any warmth has since long gone, and it’s incredible to imagine this as a place of shelter when the sailors overwintered in 1845.

We toast their simple graves with a shot of whisky as marauding grey clouds threaten to steal the remains of our day.

Surprisingly, a kayak trip along the island’s sharp rising coastline is less extreme than expected. As kittiwakes weave between threads of mossy granite spooling into the water, I’m struck by how lively the Canadian Arctic can be.

Right now, it feels overwhelmingly full.

“Pay attention to details and there’s so much to discover,” says assistant expedition leader Eva, a tough, blonde Swede who’s been navigating the Poles for more than two decades.

“If I had one voyage left in the world, it would be here,” she says without hesitation. “So much is still unknown.”

She’s right. During our seven-day journey, covering more than a thousand nautical miles, I don’t see another ship.

In a few years, of course, that will likely change. This summer, the 1,070-person Crystal Serenity sailed through the Northwest Passage, signifying mass tourism is imminent.

Whether or not this fragile environment can support so many visitors is questionable.

Equally controversial is the darker reality of increased access; the destruction threatened by climate change. Should the sleeping dragon awake, methane frozen in Arctic sea ice could double the amount of carbon monoxide in our atmosphere overnight. A thought more chilling than the biting polar air.

Ironically, the route Norwegian Roald Amundsen eventually claimed through the Rae Strait in 1906 is almost irrelevant. Today, there are multiple northwest passages and every year, new possibilities emerge.

The opportunity for discovery is undoubtedly growing. And so is our insatiable desire to explore – at any cost.

TRAVEL FACTS

:: Sarah Marshall was a guest of The Ultimate Travel Company (www.theultimatetravelcompany.co.uk; 020 3051 8098) who have a 16-day Northwest Passage voyage on the Akademik Ioffe accompanied by polar historian and broadcaster Dr Huw Lewis-Jones and the The Ultimate Travel Company managing director, Nick Van Gruisen. Costing £8,495 per person, the private expedition departs London on August 11, 2017, sailing from Greenland the following day. All meals, drinks and British Airways flights from Heathrow and onward connections are included.

:: One Ocean (www.oneoceanexpeditions.com) will operate a 10-day Pathways to Franklin voyage, departing August 14, 2017, costing from £3,933pp. Charter flights from Edmonton to Resolute from £1,200. International flights extra.