It was a time when the Roman emperor Septimius Severus launched a brutal campaign against the Caledonii in the north of the British Isles.

The Roman invasion, which lasted from 208-211 AD, resulted in Severus becoming bogged down in a guerrilla war in the highlands.

The invasion was abandoned by Severus’ son Caracalla and Roman forces once again withdrew to Hadrian’s Wall.

Conflict between Romans and Picts

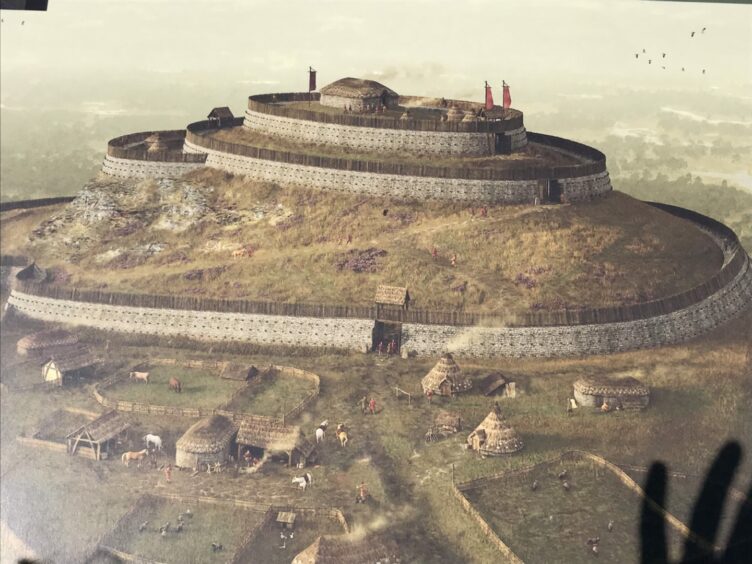

But what was the relationship between the invading Romans and the tribes of Fife who at that time had a hillfort on the East Lomond?

Did Pictish tribes in eastern Scotland begin to centralise their settlements after this brutal campaign by the Romans – laying the foundations for what became the Kingdom of Scotland?

Or was East Lomond a complicit settlement working with the Romans as they fought tribes further north?

These are just some of many questions being raised following the latest archaeological dig to take place on the upper slopes of Fife’s second highest summit.

During the first week of July, 24 professionally-led archaeology volunteers carried out excavations in the latest dig directed by Joe Fitzpatrick, chairman of Falkland Stewardship Trust.

While earlier digs were run in conjunction with the late Perthshire-based archaeologist Dr Oliver O’Grady, this is the latest dig to be run in conjunction with professional archaeologists from Aberdeen University.

What were the findings of the dig?

For archaeology volunteers, nothing beats the unearthing of something that hasn’t been seen for millennia.

However, for Aberdeen University professor and experienced archaeologist Gordon Noble, it’s less about the discovery of objects and more about piecing together a wider story which has the potential to “fill a gap” in Scottish archaeology.

Speaking with The Courier as the latest excavations were completed, Gordon said they had been concentrating on the part of the fort that was largely unknown prior to Ollie and Joe’s early work there.

During their early geophysical survey, Ollie and Joe identified a big wall and series of settlement deposits and various other enclosures south of the hillfort.

Over the last few seasons, what’s been established is evidence of a very rich settlement at East Lomond dating to the Roman Iron Age (1 – 400 AD) through to the post-Roman period.

That moves into the traditional era of the so-called Dark Ages (476 – 1000 AD) when it’s known the first Kingdom is beginning to be established in Scotland.

“The beauty of digging at East Lomond is that it’s largely untouched in comparison to lowland sites, and indeed many other hillforts,” said Gordon.

“You don’t have the same intensity of modern agricultural practices for example damaging the archaeology and in a lot of places completely removing it.

“What we’ve got is incredibly dense deposits from the 2nd/3rd century through to the 7th century.

“This year’s dig was really about following up on that and opening up a much bigger trench.

“We wanted to see the depth of deposits, the intensity of occupation and follow up on one of the trenches we dug last year which was on the annexe wall of this exterior settlement, identifying lots of hearths.”

Building on finds of previous digs

Gordon explained that this year’s dig cut through a much bigger section of the annexe wall.

It was perhaps a boundary or a defensive wall, but it also defined this area of outer settlement.

Inside the wall, what’s been really striking over the last couple of years, he said, is the density of settlement.

Over the last couple of years, dozens of hearths have been unearthed.

This shows that this site was a really substantial settlement of this time period.

“That’s really exciting in terms of discovering new information about perhaps the centralisation of settlements in this later Roman Iron Age,” he said.

“Really it’s also uncovering a type of site that we didn’t know existed before.

“We thought settlements in this time period were largely dispersed farmsteads, down in the lowlands, low population levels.

“That’s the kind of traditional view of the late Roman Iron Age and into the late medieval period.

“But certainly at East Lomond you’ve got a very busy landscape.

“It’s all really beginning to come together in terms of really outlining the significance of East Lomond and this kind of area of Fife in the southern Pictish kingdoms in the first millennium AD context.”

More work required to ‘pin down’ findings

Gordon said a lot more work is required to “pin down” the relationship between East Lomond residents and the Romans.

But what’s intriguing from the radiocarbon dates confirmed during the last two seasons is that the early phase of the finds seem to be around the third century.

That’s “quite intriguing”, he said, because that’s when the Romans establish a base at Carpow, near Bridge of Earn, under Emperor Severus.

Early work by Joe and Ollie found bits of Roman pottery at the East Lomond site, for example.

But more work is required on the dating to try and work out that relationship a bit more.

“Certainly we’ve got sites further north which raise similar questions,” said Gordon.

“Where we’ve been working at Tap o’ Noth hillfort up in Aberdeenshire, it also seems to really take off in the late 2nd/early 3rd century and again could have a connection to this big genocidal campaign by Emperor Severus, which seems to almost kind of silence the northern frontier for a couple of generations until the late 3rd century.

“That’s when you begin to get the mentions of the Picts as this kind of consolidated group who have come together to resist Roman rule.

“I think it’s really really intriguing.

“It’s a bit tantalising at the moment.

“I don’t think we could really commit to any particular scenario yet.

“But here you are right on the edge or north of the edge – what effect does the collapse of Roman rule in Britain have on these northern societies, and indeed, what are they contributing to that collapse of Roman Britain?

“The Picts are constantly at war with the Romans and if they really are consolidating a society and coming together, you can see that the Romans are effectively creating their own enemy that helps to bring about their own downfall.

“Again it’s fascinating to think about.

“Empires tend to unravel at their edges to an extent.

“I think again that’s a really interesting process and situation to think about.”

Aberdeen University input welcomed

Speaking on behalf of the Falkland Stewardship Trust, Joe Fitzpatrick said the “big thing” was having an “august institution” like Aberdeen University on board and recognising the significance of the East Lomond site.

While the 1695 Division of Commonties Act destroyed a lot of lowland features with the construction of walls trying to make Scotland more economic, royal estates like Falkland were exempted.

That’s why the archaeology today is so good. Nothing was touched up there while everything else was broken up and re-used.

Having Aberdeen University on board helps get this significance across to the wider archaeological community.

Essential role of volunteers

The role of volunteer archaeologists is also invaluable.

This year they had to shut down the advertising for volunteers after four days because they were “swamped”.

“There’s already a good healthy core of volunteers, some who have been with us since the start,” he said.

“But we also allow space each time for new volunteers.

“There’s a real passion amongst communities around the Falkland estate – Cupar, Freuchie, Falkland, Glenrothes, Kirkcaldy and Strathmiglo.

“Perthshire and Fife but mostly Fife are the core of our volunteers.

“We had 24 volunteers on this dig.

“We break it into days so as many people as possible can experience it.

“It’s a self selecting group. It’s people who are interested in local history and archaeology.

“So they bring something already and it only takes a degree of training and support from the professional archaeologists and the more experienced excavators to get people switched on.”

Joe said the feedback they’ve had since they finished has been “great”.

“People have thoroughly enjoyed it,” he added.

“They want to commit more, and they want to see more opportunity.

“If we can get people to lock on to the importance of their own local heritage – archaeology is a huge part of that – that is significant because we have had people who’ve been involved as volunteers who’ve gone on to find jobs or study archaeology at university.

“It’s a lovely way in and for us as an estate that’s trying to develop a range of ways to engage the community in active participation.

“This is a big thing for us and we want to make archaeology one of those core programmes that the Falkland estate offers to the people of Fife.”

‘Wealth of experience’

Gordon agreed that without the volunteers on this project, it would not have been possible.

He added: “As I say to the volunteers on site, we can’t do these projects without the likes of them.

“It’s just great to have that wealth of experience working with us under our direction at times.

“But equally it’s an amazing experience of some of these volunteers that you can largely leave them to it really.

“It’s great to have that team work and sense of shared purpose.”

What will happen next?

Gordon is in no doubt that what’s being learned at East Lomond “fills a big gap in the archaeology of Scotland”.

The hill is “surprisingly untouched” which is great for archaeology.

He added: “There are literally a handful of sites that have that sequence through the late Roman Iron Age into the early medieval period.”

He said the aim is to return for a dig for two weeks next year.

As well as accommodating volunteers, he wants to get more Aberdeen students involved too and get them working together with the volunteers.

“We’d like to test more areas of the annexe,” he said.

“What we’d also like to do over the course of coming years is begin to take a look at the fort at the top of the summit as well.

“How does that relate to what we have found in the annexe? And piece together that bigger story.

“That’s slightly more complicated because the fort itself is a scheduled monument.

“We’ll have negotiate with people like Historic Environment Scotland to gain that consent.

“But we have a good track record over the last 10/15 years now working on these major sites so hopefully we can do that and we can again tell this bigger story.

“Because the fort on top morphologically, we would classically say that is 7th/8th/9th centuries AD, which is later than the dates we’re getting for the annexe.

What does that mean?

“Is there some sort of fort there when the annexe was in action?

“Or does settlement and activity begin to constrict on to this summit area to a lesser number of people, perhaps as the hierarchical nature of society escalates in this developing time period of these kingdoms developing?

“Does it become a more exclusive elite settlement at East Lomond?

“We won’t know until we put spades in the ground.”