Miriam Brett had ice cream for breakfast and her mother hung red dresses from the windows of their home on Shetland.

For her anti-nuclear, Labour-supporting family, like countless others across the country, the party’s landslide election victory of 1997 was a cause for jubilation.

“I was six at the time and I just remember it being the best day,” recalled Ms Brett, who was born in Scalloway and moved to Bressay at a young age.

Her next “standout” memory on her journey to becoming politically aware came at the end of her primary school years, and the start of her attendance at Anderson High.

“My family went across to Lerwick to protest in Shetland’s anti-Iraq war demonstration, which was called ‘No In Wir Name’,” she said.

“I think that was another meaningful moment that shaped a lot of my politics and my path into politics as well.”

The contrast between those two events had a powerful impact on Ms Brett, and many others from her generation, who would break long-held family links to Labour.

“I think those are quite stark memories of exactly that – the hope and then the sort of despair, the anguish and heartbreak around the Iraq war was a really powerful contrast, in terms of two moments that stand out in terms of my very early years, an entry into the world of politics and what it means,” she said.

Ms Brett’s interest and engagement in with politics continued to grow throughout school, after which she spent a year in Australia, New Zealand, Sweden and the US as part of an “incredible and eye-opening” scholarship on an international research programme.

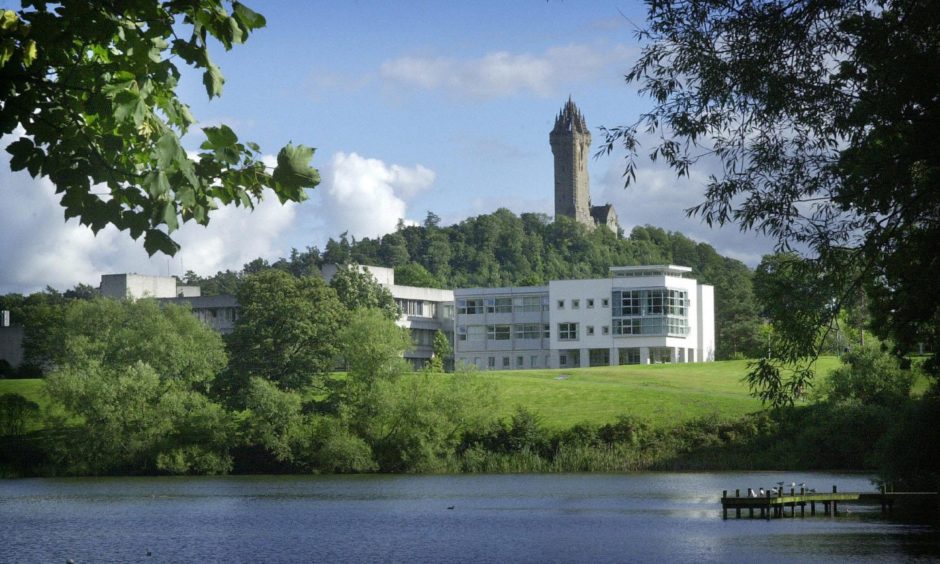

She then enrolled at Stirling University to study for a degree in international relations, focused on the work of the world’s financial institutions.

“We had absolutely incredible modern studies teachers and I think that really helped shape my passion for politics, and I was involved in an Amnesty International club at school as well, which was a brilliant introduction into the world of human rights and justice and the more international component of that as well.

“Obviously my degree was political and I was involved in various campaigns, and I co-founded a politics society at my university as well, so I was quite active at university in the political landscape, and obviously just through the process of learning more about the world of politics through my degree, became more engaged.”

Ms Brett, who was speaking to this newspaper in a personal capacity unrelated to her current job at a think tank, admitted she was initially sceptical about the prospect of an independent Scotland.

“It was really in my second year of university when the topic of Scottish independence began to gather some weight behind it and discussions started arising on campus around voting intentions, and there was a lot more organised debate and forums around this incredibly important question,” she said.

It was really there that my involvement with the SNP really began.”

“That wasn’t something that I had ever really felt inclined to support before. I think it wasn’t really something that I had ever given enough consideration to.

“A lot of my family at that point were voting No, and it really took quite a while, I think, through conversations with friends, with family members, with various groups at university, with, actually, conversations with a few of my lecturers as well, questioning some of the assumptions I had made, and engaging with some of the concerns that I had around the question of independence.

“It was really through that process that I think I got first involved in Scottish politics, and through those conversations and through that dialogue, began to support Scottish independence.

“It was really there that my involvement with the SNP really began.”

By the time Ms Brett graduated, just weeks before the referendum in 2014, she had become immersed in the campaign.

“At that point I had helped organise the Stirling University independence campaign, the Yes group there. I hosted a series of talks, debates, platforms, discussions and campaigns in and around the university, also involved in the youth movement for independence, which was incredible,” she said.

One of my favourite aspects of the campaign was seeing young people with a sense of hope, and at the notion of a radical departure from the status quo and the idea that we could reorganise our economy to work for people and challenge the way that it had worked for so long, and reinvigorate our democracy in the process of doing so.”

“One of my favourite aspects of the campaign was seeing young people with a sense of hope, and at the notion of a radical departure from the status quo and the idea that we could reorganise our economy to work for people and challenge the way that it had worked for so long, and reinvigorate our democracy in the process of doing so.

“For me, that was something I found a very inspiring aspect of the campaign.”

Ms Brett was one of the thousands who joined the SNP after the referendum result, and went to work for the pro-independence Common Weal think tank for just more than a year.

“That was a really incredible first insight into the world of work, and I’m really grateful to have had it,” she said.

After the SNP landslide election victory in 2015, Ms Brett went to work for the party’s newly expanded MP group in November of that year, soon becoming a key economic adviser.

“It was really amazing to enter a new role in such a dramatically changed landscape to what it had been only six months before,” she said.

“There was a great deal of momentum behind everything at that moment, and that was a really special time to become more involved in the world of politics.

“And it was an incredible moment for Westminster too. As much as the SNP had been in government in Scotland, at that point for a long time, I think there hadn’t really been a recognition of their centrality to Scottish politics until the 2015 election.”

At Westminster, Ms Brett worked alongside Aberdeen North MP Kirsty Blackman, who would become deputy leader of the group and an economy spokeswoman.

She said: “It has always been clear that Miriam’s passion and dedication will ensure she goes far, but she is also one of the smartest, hardest working people I’ve ever had the opportunity to work with.

“She is absolutely dedicated to pursuing fairness and equality.

“Miriam manages to combine all this talent with a fab sense of humour which means she’s also brilliant fun to work alongside.”

‘Really strong attachment to northern isles’

Theresa May’s snap general election of 2017 marked the next milestone for Ms Brett, who put herself forward to be the SNP candidate in the Liberal Democrat stronghold of Orkney and Shetland.

“I’m not sure when it first crossed my mind. I think it had maybe been something that had been at the back of my mind for a wee while,” she said.

“The idea of representing my home constituency… I’ve got a really strong attachment to the northern isles, I just think they are a very unique community, and for me they are incredibly special.

“So when the snap election was called I got a call from somebody in one of the local branches to ask me if I would like to stand.

“I felt like the rest of the dynamics kind of fell into place a little bit, because some of the barriers to running for parliament are, like, your job situation, for example, but for me I was working for the party at the time.”

Absolutely brilliant news. Never met a more talented, intelligent and down to earth person. Miriam will be a phenomenal candidate! #GE17 https://t.co/alYiLqNhmp

— Mhairi Black MP🏳️🌈 (@MhairiBlack) April 29, 2017

Ms Brett was unable to make the breakthrough, on what was a relatively difficult election for the party, compared to its preceding successes.

“It was an absolute whirlwind, it really was, because just trying to get around all the islands to meet as many people as you possibly can, and of course the constituency is between two groups of islands as well,” she said.

“So there was a lot of travel, but it was just so rewarding. I was incredibly lucky to have a group of very dedicated activists to help knock doors, even in the wind and rain, and to organise community discussions, and hold hustings.

“I look back on that as a really special time, even though we didn’t win.”

The world of politics

Ms Brett did not stand again in the seat in 2019 at the UK election, or at the Shetland by-election for Holyrood, in part because she had left her job with the party at Westminster.

She spent two years working for the Bretton Woods Project, a watchdog to the IMF and World Bank, which she described as a “really, really challenging and inspiring role”.

And since the beginning of 2020, Ms Brett has been director of research and advocacy at the Common Wealth think tank, which focuses on democratic ownership strategies, sustainable economy, and the green new deal.

“I don’t know if I’ve ever really had a very concrete plan, to be honest,” Ms Brett laughed, when asked about her future ambitions, in politics or elsewhere.

“I think I’ll hopefully always be involved in the world of politics.

“I feel very much at home in that world, and I think I will, regardless of what job I do and what role I have, I think I will always have an attachment to and an involvement in politics, and Scottish politics as well.”