Michael Alexander learns how the so-called Moon Hoax of 1835 tested out the global parameters for media credibility and ‘fake news’ in the pre-telegraphic age and aimed to send up the Creationist speculations of a Dundee Minister.

The announcement the other week that water has been found on the moon and the recent pledge by the US president to send astronauts back to the lunar surface by 2024 has rekindled fascination with our nearest celestial body.

But the moon has been firing the imagination of storytellers for centuries, not least through extravagant tales linked to a 19th century Dundee minister that it was home to alien life.

The story of the Hilltown-born weaver’s son Rev Thomas Dick is being explored as part of the Being Human festival – the UK’s national celebration of the humanities which started on Thursday November 12 and runs until November 22.

Amongst the socially-distanced and online events being hosted by Dundee University around the theme of ‘The Lunar City’, there’s an exploration of Dundee’s so-called ‘Moon Hoax’ and a special screening of cult classic Moon.

Dr Keith Williams of Dundee University English department told The Courier how the “Moon Hoax” was probably the “greatest fake news event of all time” and its connection with Dundee very much part of the city’s “buried cultural history”.

“The so-called Great Moon Hoax refers to a series of six newspaper articles headlined ‘Great Astronomical Discoveries’ that became a worldwide sensation when they were published in 1835,” explains Dr Williams.

“Beginning on August 25, 1835, they concerned the supposed discovery of an ecology and civilisation on the moon.

“The hoax tested out the global parameters for media credibility and fake news in the pre-telegraphic age.

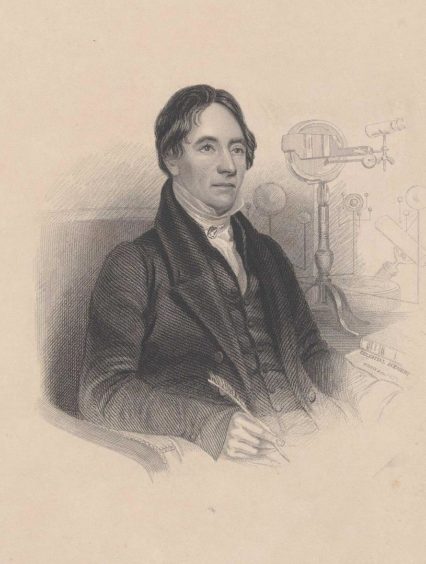

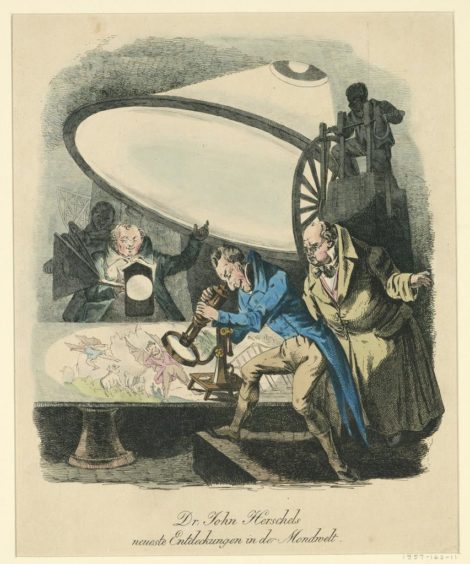

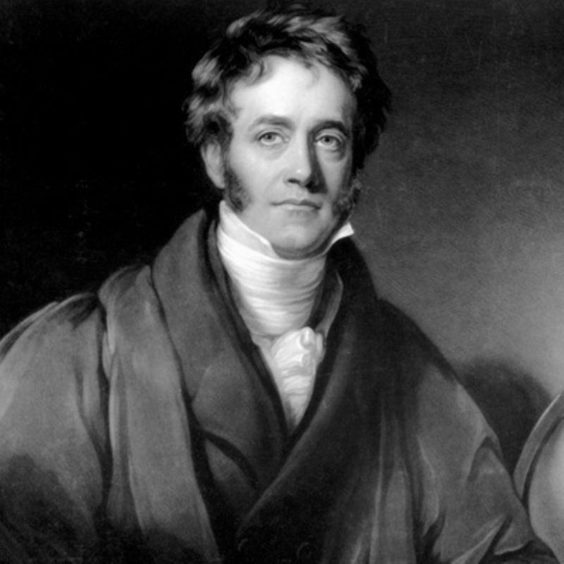

“The New York Sun, a new tabloid-style newspaper, published a series of reports, allegedly from observations by Britain’s astronomer royal, Sir John Herschel, using the largest and most powerful telescope yet invented.

“These claimed to provide incontrovertible proof that the moon was not a lifeless world, but covered in forests, seas and vast deposits of precious minerals.

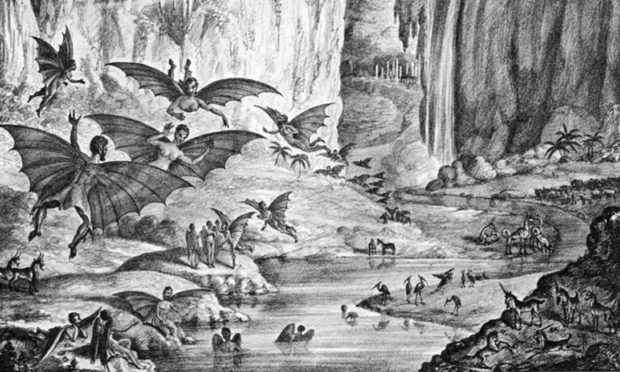

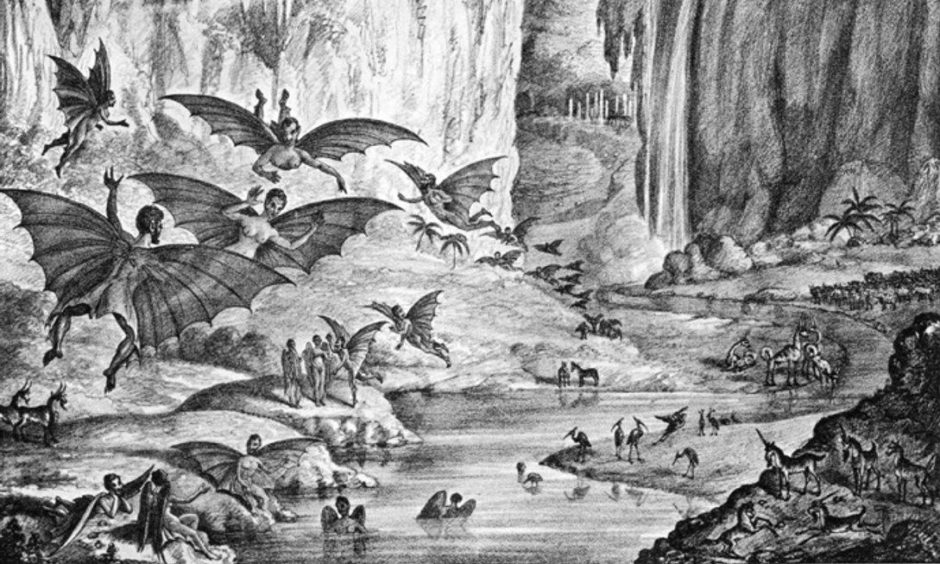

“It teemed with life forms, including bison, goats and zebras, as well as such fantastic beasts as miniature unicorns, cottage-building bipedal beavers and flying ‘man bats’ living in naked innocence and worshipping in monumental triangular temples.

“The articles gradually revealed these secrets in descriptions growing ever more sensational, until allegedly terminated when the telescope caught fire because its enormous lens, left open to the South African sun, caused it to act as a ‘burning glass’.”

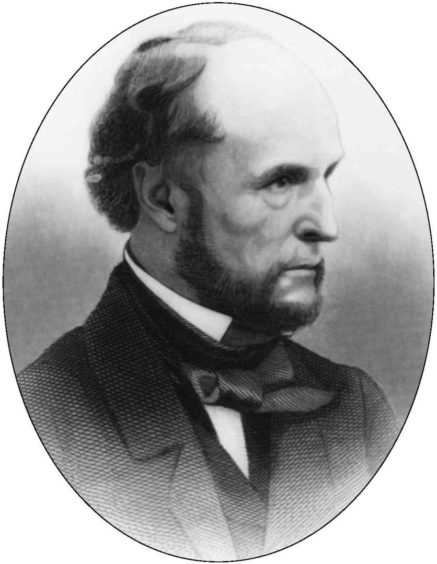

The Sun’s editor, expatriate Englishman Richard Adams Locke (1800–1871), later admitted writing the articles, not just to boost the Sun’s ailing circulation, but to satirise Creationist speculations in books by Dundee minister Rev Thomas Dick.

At the time, Dick was one of the most popular and prolific authors on astronomy on both sides of the Atlantic.

Working from his observatory, at ‘Herschel House’ in Broughty Ferry (named after his hero, whose reputation was central to the believability of Locke’s fiction), Dick’s descriptions of the planets – and even the sun – always included speculations about the kinds of ‘unfallen’ angelic beings that the Almighty populated them with, since only the Earth was subject to ‘original sin’.

Dr Williams explained that as a trained Minister, Dick believed no aspect of Creation could have been without purpose in the ‘divine plan’ at a time when, before Darwin’s theory of evolution took hold, astronomy was still a ‘safe’ science for theologians.

“Dick was probably the most well read, the most popular kind of writer of astronomical texts at that time apart from Herschel himself,” says Dr Williams, adding that Dick’s work probably had more influence in the USA where the Evangelical tradition was a lot stronger and where people were more likely to subscribe to that idea of scientific creationism.

“However, the reason why this emerged was because Dick criticised the author of the Moon Hoax who was anonymous at that time, in his book Celestial Sceneries: A Tour of the Solar System where Dick speculates about the type of beings who inhabit the moon and even the sun and so on.

“It’s really bizarre stuff. He attacked the Moon Hoax as a sort of fraud on the public which went against the divine truth.

“Richard Evans Locke replied in a letter published in a magazine basically saying – ‘if this stuff is untrue, what about your own science fictions which speculate about these inhabited worlds with no real scientific evidence beyond this kind of creed of pluralist creationism?’

He attacked Dick’s speculations as the naivest kind of ‘science fiction’.

“There was a spat between them and it was revealed that the Moon Hoax wasn’t just something that created a kind of newspaper sensation – it had a serious satirical purpose behind it which was targeted at the most well-known author of that kind at that time.”

Thomas Dick was born on Dundee’s Hilltown – the son of a local weaver – and was brought up in the Presbyterian United Secession Church of Scotland.

However, at nine years old, Dick saw a brilliant meteor, sparking his lifelong passion with astronomy.

Grinding lenses from old spectacles, he mounted them in pasteboard tubes and began his celestial observations.

Dick became a school assistant and in 1794 entered Edinburgh University, supporting himself by private tuition.

After graduating in philosophy and theology, he set up a Dundee school, taking out a licence to preach in 1801, but was soon excommunicated due to a “scandalous affair” with a servant.

However, Dick’s patrons arranged another position in Methven, where he focused on popular improvement, including democratising the study of science, the foundation of a people’s library and a form of mechanic’s institute.

Dick spent another decade teaching in Perth, during which he wrote his first book, The Christian Philosopher, or the Connexion of Science and Philosophy with Religion.

This contained an appendix on the probability of detecting signs of life on the moon and even a ‘Lunarian’ civilisation once telescopes could be developed to observe in sufficiently close-up detail.

He finally gave up teaching in 1827, building a house, equipped with observatory on Hill Street overlooking the Tay at Broughty Ferry.

Here he devoted himself to writing scientific, philosophical, and religious works which acquired widespread popularity, particularly in the USA, influencing many scientists, engineers, politicians, writers and thinkers, including intellectual luminaries such as Ralph Waldo Emerson.

Dick received an honorary doctorate of LL.D from Union College, New York, and admission to the Royal Astronomical Society in 1853.

Despite his writing’s enormous reach, however, Dick enjoyed scant royalties due to naïve arrangements with his publishers.

He died at 82 in 1857 and is buried under a massive rocket-like, pink granite obelisk in St Aidan’s churchyard, Broughty Ferry.

A significant legacy is Dundee’s Mills Observatory which was created from money bequeathed by one of Dick’s devotees, John Mills.

Dr Daniel Cook, Being Human lead for Dundee and a senior lecturer at the university’s English department, said the Moon Hoax is a highly significant event in Dundee’s forgotten cultural history, but also of science fiction in general.

The connection was unearthed through the work of a Dundee University PhD student who was researching the work of local science fiction writer Robert Duncan Milne, who emigrated to the USA.

In a previous years, the Being Human festival highlighted Dundee’s links to Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, Jonathan Swift and HG Wells.

This year, with a “lockdown to countdown” mentality, they were heading to the moon and back, figuratively speaking, with a programme that features everything from lunar storytelling and crafts to a day in the life of an astronaut, out of this world poetry and the launch of new comic books.

“The moon is the ‘ultimate blank page’ upon which we project our very human endeavours but also our anxieties,” says Dr Cook.

“The moon is often a sign of nightmares but it’s also a sign of hope – we want to travel to the moon.”

Already established as the UK’s annual celebration of humanities research, Being Human boasts a diverse range of events delivered by academic researchers in collaboration with community and cultural partners. As expected, given the pandemic, online activities have come to the fore.

Led by the School of Advanced Study, University of London, and funded by the Arts & Humanities Research Council and the British Academy, Being Human is a national forum for public engagement with humanities research.

The festival highlights the ways in which the humanities can inspire and enrich lives, helping us to understand ourselves, our relationships with others, and the challenges we face in a changing world.

Events include the online screening by DCA between 12.30pm and 1.30pm on November 22 of From the Earth to the Moon in 10 Easy Steps (2020) by local artist Chris Gerrard.

The homage to experimental film splices together classic clips with some new footage to tell the true story of Dundee’s moon hoax, as well as humanity’s long-held obsession with space travel.

This will be followed from 2pm to 4pm with Duncan Jones’s Moon (2009).

More information about all the Dundee events can be found at beinghumanfestival.org