As raucous Burns suppers again take place across the world, a Dundee University professor tells Michael Alexander how Scotland’s bard was taken far more seriously during the 19th century.

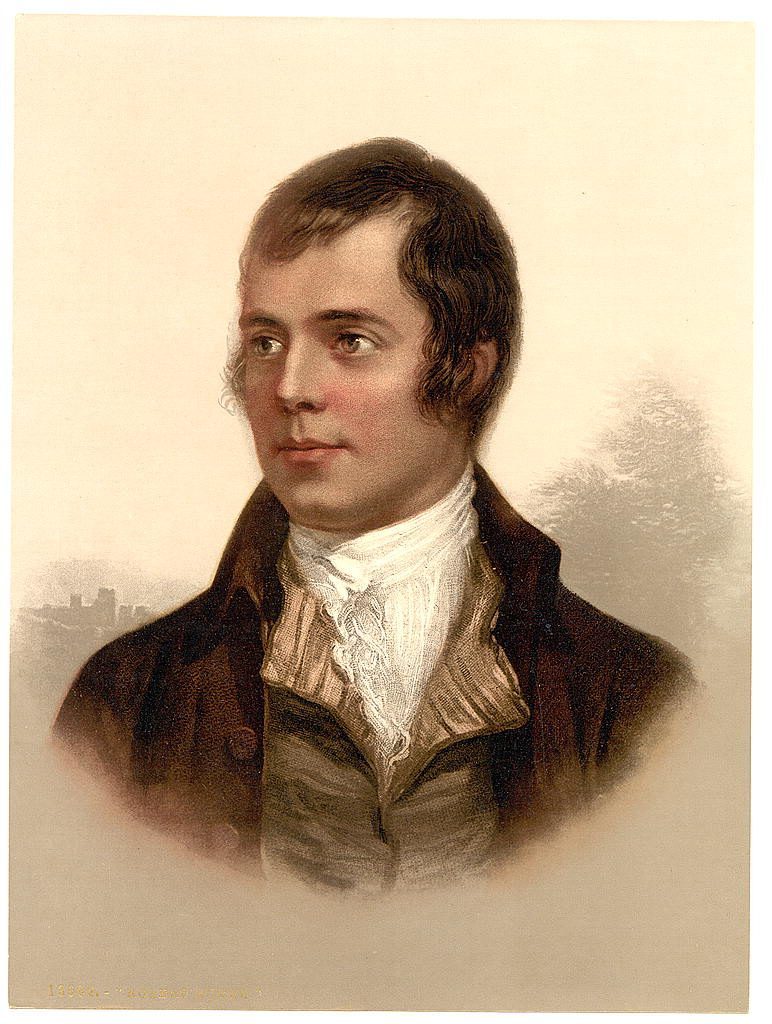

Scotland’s best known poet Robert Burns only made one visit to Dundee – a relatively low key trip in September 1787 during which he described the city as a “low lying but pleasant town”.

But that didn’t stop up to 100,000 people from taking to the streets of the city for the unveiling of a commemorative statue to the bard some 84 years after his death.

There were unprecedented scenes when the bronze statue, designed by Scotland’s then leading renowned sculptor Sir John Steell, was unveiled in Albert Square, outside of the McManus Galleries, in October 1880.

The statue was inspired by the opening verse in the poem ‘To Mary in Heaven’ – that Burns was looking skywards in thoughts of his lost love, Highland Mary (Mary Campbell).

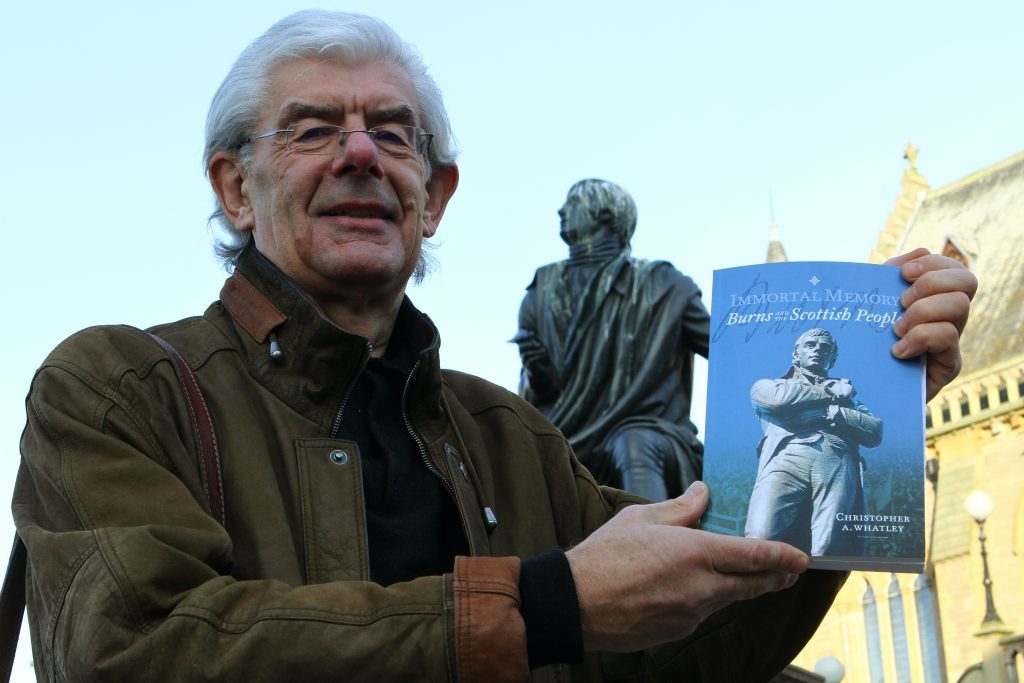

But according to Dundee University professor of Scottish History Christopher Whatley, there should be little doubt the hold that the Burns legacy had on the imagination of Victorian Scotland – and in particular the inspiration that he gave to the ‘working man’ all those years after his death.

“It was the biggest crowd ever to assemble in Dundee’s town centre,” explains Professor Whatley, who started investigating the history of Scotland’s Burns’ statues ahead of the 250th anniversary of the bard’s birth in 2009.

“Albert Square was mobbed – not polite crowds but active crowds, ebbing and flowing like a pop concert crowd, surging to touch this statue or hear what was being said.

“All the roads to the square were lined with people. People came on excursion trains to take part. There were probably 100,000 people involved – quite remarkable when you consider the city’s population was only 150,000 at the time.

“But what was also striking is that working people in particular were the bulk of the audience – and whilst it sounds trite, there were good reasons for that.”

In his new book ‘Immortal Memory: Burns and the Scottish People’, Professor Whatley explores the idea that Burns was at the heart of the “palpable rise” of Scottishness that swept the country from the 1840’s through to the First World War – including demand for Home Rule.

Whatley says that if Sir Walter Scott imagined Scotland, then Burns shaped it – giving ordinary Scots in what had been one of the most socially uneven societies in Europe a sense of self-worth and dignity, and underpinned demands for political and social justice.

Scotland in the 18th/19th centuries was a society where a voiceless people, who did not have the vote, were expected to know their place by showing deference to an immensely powerful landed class and the church.

It was also a time when following the 1707 Act of Union between England and Scotland, frustration was growing amongst the masses about the British Government’s reference to Scotland as ‘North Britain’ and a growing sense that Scottish identity and culture was being lost.

So when Burns came along as a ‘man of the people’, presenting himself as the ‘Ploughman Poet’ with songs about self-worth and dignity written in the familiar language of the people – Scots – he was a hit amongst many ordinary people who at last heard the radical notion of equality being articulated in their own tongue.

Even long after his death in 1796, his works – many of which “shook the presbyterian cage” and were subsequently criticised by the church – were regarded as somewhat controversial ideas with pirate copies doing the rounds in pamphlet form at a time when attempts were made to suppress them.

Yet Professor Whatley says until now, historians have been guilty of overlooking the real influence Burns had with a direct line drawn between then and the foundations of a more open, liberal Scotland that exists today.

He adds: “So much has been written about Burns. Library shelves are heaving with books and papers on Burns himself – his life, his work. But nobody has seriously looked at Burns’ influence on Scottish society. In other words, my profession – historians – have kind of left Burns to the literary scholars.

“The historians who have mentioned him tend to get him wrong. They associate him with nostalgia and argue that Burns was loved, appreciated, because of his capturing of a Scotland gone if you like.

“My case is that Burns was partly about these softer aspects of life, but that he was an enormously influential factor in Scottish society. He wasn’t just a useful add on who reflected. It was more than that. He inspired and elevated the Scottish people.”

Today, on the 258th anniversary of his birth, more Burns suppers than ever will be held worldwide.

And yet Professor Whatley is conscious that Burns is perceived very differently today than he was in the 19th century.

“I’m not knocking Burns suppers,” he says, “but these days they are more of an excuse for a good time. That’s very different from the Burns of 100 years ago who was an enormously serious figure in Scottish society.

“I’m not saying Burns has become a joke. But he has become lightweight in a sense.”