An insight into the life of Victorian Scotland’s “forgotten” poets published in Dundee has been brought back for a modern audience.

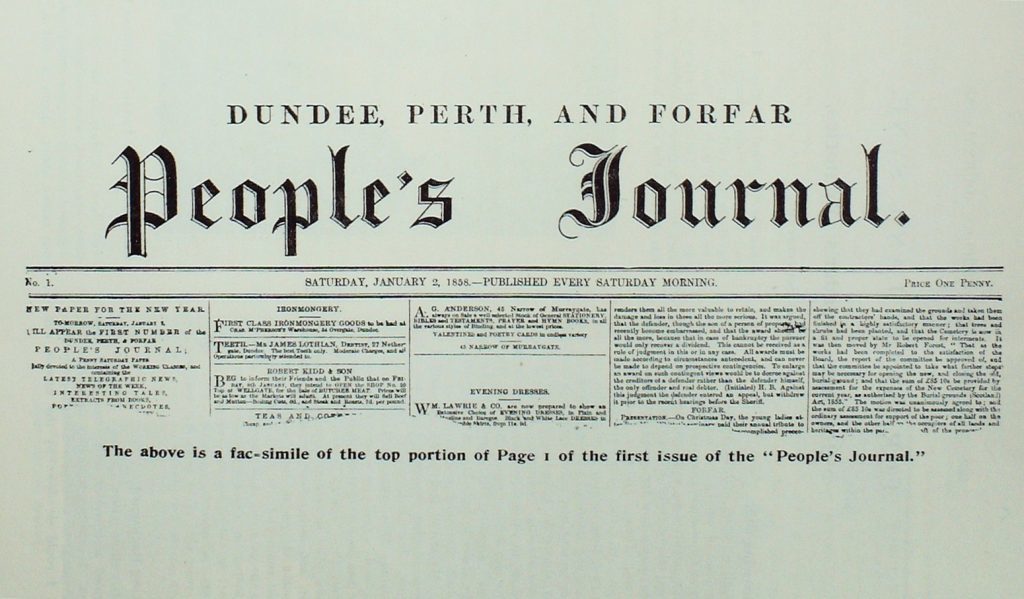

The People’s Journal, printed by John Leng & Co and then DC Thomson in the city edition between 1858 and 1986, was billed in the 19th Century as “a penny Saturday paper devoted to the interests of the working classes.”

Each edition included poems by people from all walks of life across Tayside, who used the format to talk about strikes, trade unions and politics, among many other topics.

Strathclyde University academic Kirstie Blair has collected more than 100 of these poems from 1858 to 1883, in a volume entitled Poets of the People’s Journal: Newspaper Poetry in Victorian Scotland.

Publishers the Association for Scottish Literary Studies hope the book will give modern readers a “vivid portraits of their writers’ lives”.

Contributors would send in material under their own names and pseudonyms such as Eriphos, Harpoon, and Trebor.

The collection also illustrates how the infamous poet William McGonagall, represented by An Address to Thee Tay Bridge from September 15 1877, was part of a wider culture of “bad” verse in papers.

Professor Blair said: “It was a popular practice for many people in the 19th Century to go home after work and write a poem.

“A lot of them had extremely hard lives but it was an aspirational and highly regarded pursuit.

“It was also a badge of pride for them to display their literacy skills.

“People in Scotland in this period were very proud of the idea that Scotland had more ‘people’s poets’ than any other nation on earth, and every Scottish town or village had its own bard.

“There was a great deal of competition between towns and local readers followed the careers of ‘their’ poets.

“A lot of these poets are entirely forgotten now because they were published in newspapers, rather than in books or magazines, but the poetry is of a far higher quality and far more entertaining than might have been thought.

“The book includes poems by and about William McGonagall, who has become known as ‘the world’s worst poet’, though I show here that he was actually part of an established culture of deliberately bad newspaper poetry and became a major comic poet through it.

“Most of these poems cover subjects which are surprisingly relevant today.”

The anthology also contains selected poems from the People’s Friend, which was originally a spin-off from the People’s Journal and is still published today.

The growth of weekly news

Newspapers of the early 19th Century were subject to stamp duty of up to four pence per copy, which made daily consumption of news too expensive for many working-class readers.

Weekly digests offered a cheaper option, and provided an outlet for a wave of Scottish writers.

Following the success of publications such as the People’s Journal, poetry and fiction were often introduced to daily newspapers, and this material was often a way around paying more stamp duty.

After the tax was repealed in 1855, many writers in Scots enjoyed a surge in readership, and the popularity of serialised books continues to this day.

The Journal’s most influential editor, Fife autodidact William D Latto, first appeared in the paper as a contributing writer.

His “Tammas Bodkin” columns helped popularise the use of Scots in the Victorian print era.