Ahead of an RSGS talk, Michael Alexander speaks to zoologist and conservationist Mark Carwardine about the stark threat to global wildlife – and why he hasn’t given up hope.

It was the moment that a rare kakapo bird called Sirocco hopped on to zoologist Mark Carwardine’s head and attempted to mate with him, prompting TV presenter and former Dundee University rector Stephen Fry to say: “Sorry, but this is one of the funniest things I’ve ever seen. You are being shagged by a rare parrot!”

The hilarious incident at Codfish Island, New Zealand, happened in 2009 while they were filming Last Chance To See – a series that saw the unlikely duo travel the world in search of a motley collection of endangered species.

A video of the kakapo incident has since had more than 100 million hits on YouTube with Sirocco becoming a major celebrity in New Zealand while raising awareness as an official spokes bird for conservation.

“If I had to name one thing I’m really happy came out of Last Chance to See that would be it,” smiles Mark, adding that in the 31 years since he did the first Last Chance To See series with the late Douglas Adams, author of The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy, in 1989, kakapo numbers have risen from 40 to a “still teetering” 200.

But if the lesson of Last Chance To See is that predictive conservation is vital – that the longer you leave endangered species the harder and more expensive it is to bring them back from the brink – then he is far more gloomy about the prospects for wildlife in general.

Of the eight species he and Douglas Adams studied in 1989, the Yangtse river dolphin of China is now extinct and the northern white rhino of the Congo is extinct in the wild with only two left in captivity.

Extinctions

It’s a situation he finds “very scary” and a reminder that despite the huge amount of time, money and effort invested worldwide trying to protect them, and the success in getting more people interested in conservation, a lot more still has to be done.

“Generally speaking in 25 years the best we’ve all achieved in conservation is to slow the decline,” says Mark.

“The honest truth is that most species are worse off now than they were 25 years ago.

“But without conservation many would have gone altogether.

“I have this conversation with friends who have been in conservation for decades, and we all say the same thing that it’s very depressing but that’s what keeps us going. Without conservation it would be worse.”

Mark says the conservation world was undoubtedly very different 30 years ago with fewer members of the public as aware.

That was one of the reasons for involving Douglas Adams in that he had a massive following through Hitchhikers Guide to the Galaxy and they hoped his fans would be inspired to pick up the original Last Chance To See book.

Lifelong love of animals

As far as his own life is concerned, working in conservation is all the now Dorset-based 61-year-old ever wanted to do.

One of his first memories as a boy was standing in St James Park in London with his arms out stretched and his dad putting bread on his arms and head as pigeons and sparrows came down to feed.

He did a zoology degree and puts his career since down to “pure luck” – working for WWF, working in radio and TV and writing more than 50 books.

When it comes to the general public, he thinks most people “get” conservation now and understand why it’s important. In surveys many are even prepared to pay for it.

But the challenge is getting politicians to enact meaningful change away from the soundbites.

“David Attenborough is saying this and everyone I know in conservation agrees,” says Mark.

“If we don’t get our act together in the next couple of years we’ve lost it basically.

“It sounds like you are walking around the streets with a placard saying ‘the end of the world is nigh’.

“But the challenge is getting politicians to see it as more than just green votes and ticking boxes.

“I think in the UK one thing we need to do is make environment part of our whole development process.

Integration

“To have it integrated into all the other departments – transport, education and everything else.

“The real challenge is for the rest of us to persuade the decision makers that this is absolutely fundamental and that it’s all very well setting targets ready for COP for climate change. You’ve actually got to meet the targets.

“Politicians are good at talking the talk without walking the walk.

“The big challenge for the next few years is to change that.

“Without the politicians firmly on board, taking action and not just talking about it, then I really fear for the future. And the next few years is going to be critical in that.”

Message of hope

Mark concedes that this all sounds “doom and gloom”.

But he also carries a message of hope, which is why he refuses to yet give up.

On January 13, Mark will be giving an online talk to the Perth-based Royal Scottish Geographical Society.

It’ll focus on the pros and cons of writing a field guide.

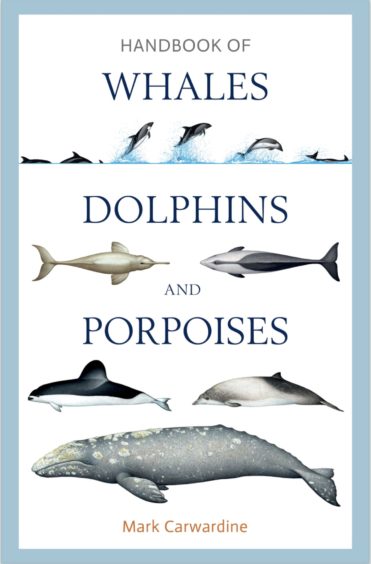

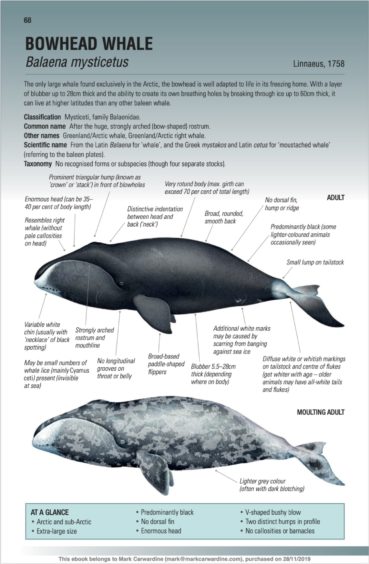

About 25 years ago, he wrote a field guide for whales, dolphins and porpoises. It was the first of its kind.

But when he looked at it again a few years ago he realised it was out of date and “getting embarrassing” so decided it was time to do a new one.

Embarking on the project that he thought would last a year, it took six years solid work involving hundreds of whale experts around the world.

“I’m going to be talking about what’s involved in producing a guide like that,” he says, “and advising everybody if a publisher sidles up to them and says ‘do you want to write a field guide?’ Say no!

“Much as I’m really happy with it – it’s incredibly satisfying – it’s unbelievably hard work!” he laughs.

In a non-Covid world he’d have been visiting Perth in person as part of a mini UK tour.

It would have been an opportunity to visit the country he loves – Scotland.

“I’m genuinely not just saying it, but if I could live anywhere in the world, it would be the Black Isle,” he says.

“I love it and everything about it. The wildlife is fantastic. I love the wilderness.

“The dolphins, the wild cats, birds of prey – you’ve got everything on the Black Isle. It’s just wonderful. And for a wildlife photographer you just wouldn’t have to leave there! I love it.”

However, with much of his work –whale watching and wildlife photography trips – involving travel and therefore cancelled, the talk is part of his Covid-reinvention which has also seen him start a YouTube channel for the BBC on wildlife photography.

He’s been running sessions on how to do things like photograph birds in the locked down garden.

That’s another area where he’s taken positives from these difficult times.

“People are for the first time taking note of what’s around them and noticing things they wouldn’t notice before because people are rushing around all the time and not stopping,” he says.

“I think that’s a really healthy thing – interest in nature and conservation definitely grew during lockdown.

“I think more people are taking an active interest in things like climate change now simply because they didn’t realise what it was like with no planes in the sky and fewer cars on the roads. It’s got a flip side as well.”

Reliance on tourism

But while it’s great to cut down on travel, many conservation projects and a lot of wildlife around the world rely on tourism.

The classic example is the mountain gorillas of Central Africa. Without eco-tourists there would be no mountain gorillas, he says.

“There are many other cases where the funding has dried up for anti-poaching patrols and on the ground conservation work,” he adds.

“I think the lesson is to get a happier balance and to cut back on some of that and to make it more responsible and aimed at the conservation side of things – not just mass tourism.

“We’ve got so much fantastic wildlife in the UK – particularly in Scotland. There are loads of amazing things here. We’ve got access, there’s all sorts of amazing reserves and hides. Lots of people to help and introduce other people to wildlife.

“We are in an ideal position – if you love nature and wildlife – and much as we moan, have our problems and lots of wildlife is declining – there is still a lot here and the more people take an active interest in it the better.”

*For more information on Mark’s online RSGS talk on January 13 at 7.30pm, go to https://www.rsgs.org/event/mark-carwardine-never-ever-ever-write-a-field-guide