It’s time to retire the phrase “cost of living crisis”.

All those who have contributed to its devious grip on the public discourse, including me, should hang their heads in shame.

It’s absolutely right that people are facing an intense financial squeeze, of course.

Domestic fuel costs have shot up. And as Martin Lewis warned recently, they’re likely to go up another 64% in October.

Inflation more generally is biting, with consumer prices rising 9.1% over the year to May. And as Jack Monroe has pointed out, it’s much worse even than that for those on low incomes.

Inflation on that scale turns what might have been a semi-decent pay rise a few years ago into a cut, in real terms.

The most recent data from the Office for National Statistics shows that overall pay fell by 2.2% over the year to this April.

So it’s happening. But the problem is the terminology.

It’s so abstract. No one is at fault. It’s just … happening.

Except that’s really not the case.

Now some of the elements are indeed external to the UK.

Try as I might I can’t blame the UK Government for Putin’s invasion of Ukraine, or its subsequent impacts on food and other prices.

NEWS:

I feel sick writing this!

I've just got the latest price cap predictions from @CornwallInsight. A huge spike in the key year-ahead wholesale price meansOCT cap prediction UP 64% (so £3,244/yr on typical bills)

JAN cap prediction UP 4% (so £3,363/yr)/contd

— Martin Lewis (@MartinSLewis) July 8, 2022

But break the cost of living crisis down into its two halves – depressed pay and rising prices – and it’s clear this is no act of God.

What we are seeing is the direct and intentional effect of government policies.

The rich get richer and there’s not much the poor can do about it

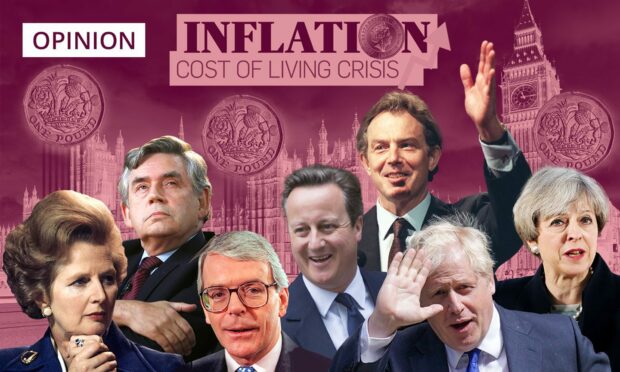

Let’s start with incomes. The redistribution of wealth, from poor to rich, has been Britain’s underlying economic strategy for more than 40 years now.

In crude terms, workers create wealth for private companies. It is either reinvested, or it flows to them, or it flows to shareholders.

As Unite showed last month, there is no crisis of income for shareholders.

Instead, the FTSE 350 saw profits last year 73% higher than the year before.

Meanwhile the national minimum wage remains below £10 an hour (or £6.83 if you’re 18-20).

Employers know they have a government at Westminster that will always take their side against workers – and a main opposition party where MPs who support striking staff risk disciplinary action.

That makes it seem much less risky to squeeze wages. And 40 years of anti-trade union governments have undermined workers’ ability to push back on that squeeze, especially outside a few key parts of the public sector.

Cost of living comes down to Westminster policies

Now look at the other half of the problem. The rising cost of living is also a function of decisions made by government, largely but not entirely at Westminster.

The French kept their power companies in public hands. And so their costs rose just 12.6%, compared to the 54% hike here.

France is also less dependent on fossil fuels, largely because their response to the 1973 oil crisis was a massive programme of building nuclear plants.

When Westminster privatised electricity supply here, in the 1990s, the private operators turned to gas plants. Even now more than a third of the UK’s power comes from gas when what we needed was a dash for renewables, owned in the public interest.

This gas dependency has put us in a weaker position during both a climate crisis and a proxy war with Russia.

It is also entirely a consequence of policy decisions designed to asset-strip the public sector and focus on rewarding shareholders.

And it drives up energy costs to the British public and industry alike.

Rocketing housing costs, for those who rent, are another direct result of specific policy decisions.

There is no shortage of houses in this country. It’s just that too many of them have been turned from homes into businesses.

And just as the interests of shareholders have been systematically favoured over workers, power has shifted further from tenants to landlords.

Solutions exist – but they’re not on the table

The very essence of Conservative and New Labour economics is to promote those who earn without working, those who live comfortably off your labour.

That’s why these issues have got no traction in the Conservative leadership debate.

At best, they’ve offered loans as a response to rising bills. So you can keep handing money over to energy companies and ensure shareholders can keep earning.

But the solutions are there, just as they are for the climate breakdown.

They would require a return to public ownership, so utilities are run for our benefit.

They would require a restoration of workers’ rights, so pay and conditions aren’t constantly ground down.

And they would require the transformation of the private rented sector into social housing, with fair rents and security.

But these changes are way beyond the bounds of acceptable political discourse, which defined even Corbyn’s tepid social democracy as a communist threat to our very way of life.

Reshaping our economy to make life comfortable and affordable for all – and eliminating extraordinary disparities of wealth and power? This is simply not on the table.

So yes, there is a crisis. And it will only get worse. But let’s stop implying that this is just an inexplicable set of circumstances.

This is the economy working the way every Westminster government since 1979 has intended it to work.

Conversation