Observing her appearance at the UK Covid-19 inquiry in Edinburgh this week, it is clear there are three things Nicola Sturgeon wants us to believe.

She wants us to believe she was only following guidelines when she deliberately deleted records of her decision making during the pandemic – and that, in any case, everything that needed to be recorded was recorded anyway.

“Trust me”, she said, with everything but words.

Equally, Sturgeon wants us to believe that – contrary to evidence from senior civil servants – the Scottish Government was not, actually, “asleep at the wheel” in the early stages of the pandemic.

“If anything, I was too wide awake”, the former first minister said, again with everything but words.

Above all – and this one included amateur dramatics for emphasis – she wants us to believe that she did not politicise the pandemic.

“Who, me?” she said, and this time with quite literally everything but words.

‘How can we believe any of this?’

The question facing us – the audience – is how can we possibly believe any of this, when it so clearly flies in the face of everything we saw during the pandemic, and everything we have learned since?

Let us take the politicisation point as an example.

First of all, there is the documentary evidence – or, at least, what is left of it.

This shows repeated, concerted, and deliberate attempts by the Scottish Government to use the pandemic to advance the cause of independence.

For instance, we have the message from Liz Lloyd, Sturgeon’s long-term consigliere, where she quite clearly states her desire to ferment a row with the UK Government for a political purpose: “a good old-fashioned rammy” as Lloyd did, precisely, say with words.

Equally, there are the cabinet minutes from June 2020 – just a few short months after the first lockdown was announced – which show Sturgeon and her ministers “agreed that consideration be given to restarting work on independence and a referendum” using “the experience of the coronavirus crisis”.

Again, words.

Most bizarrely, there is even the SNP government’s suggestion that quarantine restrictions against Spain would have to be lifted or else “there is a real possibility [the Spanish government] will never approve EU membership for an independent Scotland as a result”. Again, words.

(And, as an aside to the Scottish Government’s diplomats, there may be other reasons why Spain – a country that recently imprisoned people for merely holding a referendum on secession – might be reluctant to embrace an independent Scotland).

TV briefings

As well as this documentary evidence, our own experience during the pandemic – our eyes and our ears – tell us Sturgeon politicised it.

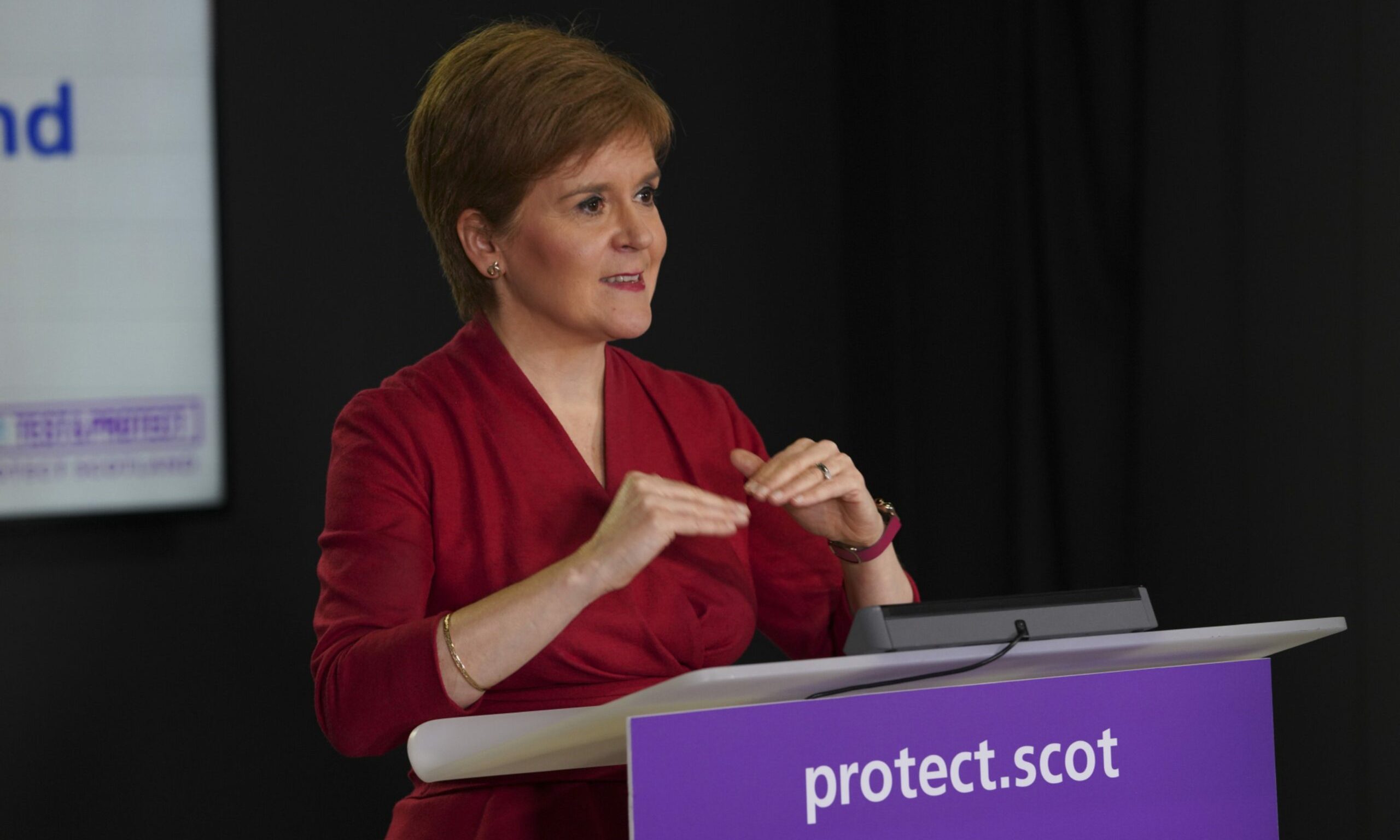

There were the daily briefings, broadcast on primetime TV to every home in the country, that featured Sturgeon front and centre.

These dragged on for far longer than those elsewhere in the UK and featured a far less varied cast.

Indeed, they became so akin to a daily party-political broadcast that broadcasters eventually felt compelled to add in opposition voices for balance.

Then there was Sturgeon’s proclivity for pre-emptive announcements, where the then first minister sought to gazump – in some cases by just a few minutes – the UK Government.

Why would you do this unless you were seeking to politicise the pandemic?

Why would you do this unless you were trying to accentuate a narrative that one government was leading, and another government was following?

Political animal

Equally, there was the desire to cast the Sturgeon government as cautious, the Boris Johnson government as cavalier.

Often this manifested itself in slightly – ever so slightly – different rules or timeframes to the rest of the UK.

However in other instances – such as school closures that damaged the educational prospects of a generation – the consequences of the politicisation of the pandemic were much more severe.

But, perhaps most importantly when choosing whether to believe Sturgeon, there is what we know of the woman herself – that she is, above all else, a political animal.

She has been an elected politician since 1999, was a senior minister for more than 15 years, and a party leader for almost a decade.

She lives and breathes politics. In many ways, it is her brilliant political instincts – her intuitive ability to read and respond to a political mood – that are her finest asset.

And that is ultimately why it is impossible to believe her claim not to have politicised the pandemic.

It was, after all, the closest Sturgeon ever got to making a significant breakthrough on her most cherished cause – Scottish independence.

Indeed, had she not been thinking about independence at the height of the pandemic – when her and her party’s popularity was soaring, while the prime minister’s was plummeting – it would have been a betrayal not only of her deepest instincts, but the party and movement to which she has dedicated her life.

And to make that point, at least, no words from the former first minister are needed, either.

Conversation