“Stop picking at it, you’ll make it worse.”

I must have heard this at least once a week throughout my childhood.

Whether it was a sore loose tooth, an itchy scab healing over a skinned knee, or a midsummer midge bite gone crusty, I was never one for leaving pain alone.

You’d think I’d grow out of it, but as the internet grew alongside me, search engines gave me a whole host of new possible pains to poke and prod at.

These are, of course, the hypothetical health conditions and maybe maladies that afflict any minor hypochondriac with Wi-Fi access.

Over the years, and with the help of Dr Google, I’ve diagnosed myself with brain tumours (migraines), arrhythmia (three shots of espresso in one afternoon) and deep vein thrombosis (calf cramps).

Now, like my long-suffering friends, partner, parents and GPs, you might wish to tell me to ‘step away from the search engine’.

It’s accepted wisdom that Googling your symptoms will only solidify the idea that no, this is not a tension headache and yes, I am in fact going to die tonight.

So we’re generally encouraged to spare ourselves the anxiety of the WebMD deep dive.

Research rules in favour of symptom search

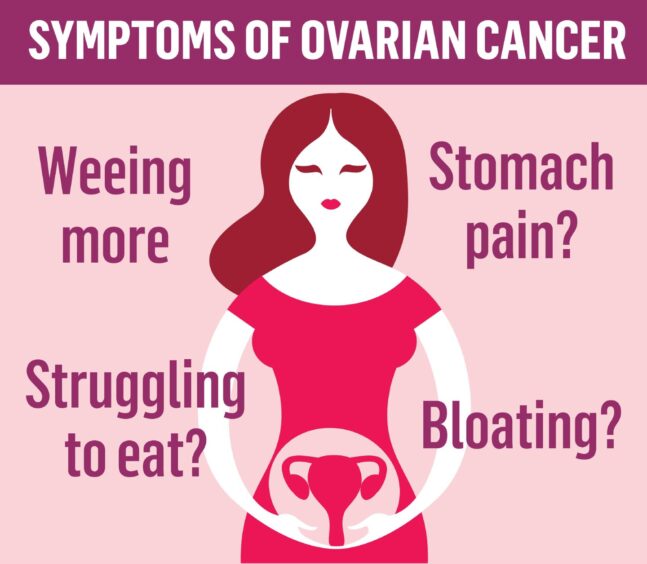

However, vindicating new research from Imperial College London has revealed that Google search data could help identify cases of ovarian cancer months ahead of GP referrals.

The study of 235 women over 18 months found that many were looking up symptoms such as weight loss and bladder problems almost a year (360 days) before being referred to cancer specialists.

And that data scientists were able to identify “different symptom patterns” between the searches of those who did and didn’t have cancer.

This is huge news for those at risk of ovarian cancer, because even though it is the sixth most common cancer in the UK, there is not currently a routine screening process for it.

So it’s hoped that larger studies could use the search engine data of those looking up their symptoms to help with early detection of the disease.

The upshot of this is that Googling your symptoms might contribute to saving someone else’s life – not just your own.

But it also invites a wider conversation about self-diagnosis, and the role it can play in our obviously ailing healthcare system.

Self-diagnosis: Doctors’ friend or foe?

Despite my paranoid tendencies, I’ve flip flopped between advocating for self-diagnosis and eyeing it sceptically.

In an ideal world, any health complaints would be firstly believed, secondly investigated and thirdly documented in detail by frontline healthcare workers.

And as grateful as I am for our NHS, we all know that this simply doesn’t happen across the board; particularly when it comes to women’s health.

No one can know a body as well as the person living in it.

And now that the entirety of human knowledge can be accessed at the tap of a finger, I see absolutely no reason why we shouldn’t be researching our own symptoms if we believe something is wrong.

But obviously it’s important to be discerning about your sources online.

Self-diagnosis becomes dangerous when a simple search leads to endless scrolling, stressing yourself out and creating an algorithmic echo chamber which tells you over and over that you definitely have a certain condition or illness.

I know, I’ve been there. It’s not conducive to feeling better, I’ll tell you that much.

And according to Dr Jennifer Katzenstein, co-director of the Centre For Behavioural Health at John Hopkins, this can be especially harmful to children or teenagers, who may be inclined to pathologize perfectly typical experiences after relating to the symptoms of certain mental conditions.

The truth is, if you’re worried about something, whether physical or mental health related, then visiting a healthcare professional is the essential next step.

The internet can help you show up informed, but generally, diagnosis and treatment should be left to the experts.

Ruling out illness is not a waste of GPs’ time

Still, even if the conclusion reached by the patient is ultimately incorrect, surely their own research process can only help the diagnosing clinician.

Especially in light of the new research, self-diagnosis should be treated as a valid preliminary tool for formal diagnosis.

Worst case scenario, someone walks into a GP’s office with a self-diagnosis and nothing medically wrong.

To me, spending 10 minutes to reassure someone they are OK is always better than having to say: “I wish we’d caught this sooner.”

And as a self-confessed hypochondriac, I feel the need to reiterate that I don’t actually want anything to be wrong with me.

My own habit of symptom Googling may be part doom-mongering, but it’s mostly an attempt to reassure myself that I’m fine.

Either way, it’s my way of gathering information about what’s going on with my body.

And it’s worth the risk of wasting time – my own, or my GP’s – if it means that when the Big Bad comes for me, I’m 360 days ahead.

So for now, leave me and my chronic case of compulsive symptom Googling in peace.

Conversation