As lockdown smothers the snowsports industry, ski jump legend Eddie the Eagle reminisces about his time working at Glenshee in the 1980s.

With his wispy moustache, trademark grin and supersized milk-bottle specs which steamed up on the slopes, Eddie ‘The Eagle’ Edwards was mocked mercilessly by the ski industry.

But the plasterer from Gloucestershire rocketed to stardom as Britain’s lone, and last-placed, ski jumper at the 1988 Winter Olympics in Calgary.

He was billed as the underdog – the lovable loser who captured the hearts of the nation by failing in his quest for glory.

Eddie, whose real name is Michael Edwards, was the first competitor for 60 years to represent Great Britain in an Olympic ski-jumping competition.

Under-funded and under-prepared, he famously finished last in both the 70m and 90m events.

In some eyes, it was a heroic failure. But to most, Eddie was a true hero whose perseverance and dedication paid off.

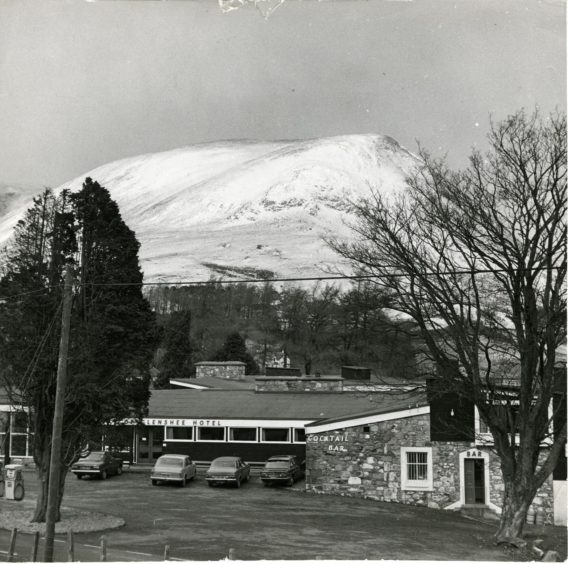

Glenshee

Five years before the Calgary Olympics, Eddie worked as a ski instructor in Glenshee.

“I’d been touring round Europe in my VW caravanette and I decided to hotfoot it to Glenshee in 1983,” says the 57-year-old.

“I went there primarily to race, but I got a job with the Cairnwell ski school and ended up working there and staying in Glenshee for eight to 10 weeks.

“We didn’t get great weather unfortunately – there were only a handful of clear blue sky days.

“The rest of the time it was either misty, foggy or cloudy. And sometimes the wind would blow you up the hill faster than you could ski down! It was harsh at times!”

Eddie remembers “a lot of ice” at Glenshee but says: “If you can ski on ice, you can ski anywhere, on anything!

“The Tiger (a notorious black run) was often sheet ice. You just grit your teeth and weaved your way down.

“Sometimes there was lovely powder snow and sometimes it was bare with rocks everywhere, or slushy.

“It was before I got into ski jumping but I was quite comfy jumping off moguls and doing tricks like spread eagles and the ‘daffy’.”

Eddie alternated between camping in his caravanette in Glenshee’s main car park and renting a room in a house at the Spittal of Glenshee.

“All I had to do was sort some food and feed myself,” he recalls.

“It was a combination of sleeping in the caravanette and having a room, which was great on really cold nights because I could have a nice hot shower and be in the warmth.”

Eddie recalls taking part in the Smirnoff British Speed Skiing Championships on one of Glenshee’s “back slopes” in 1985.

“Unfortunately it wasn’t a very steep slope,” he laments.

“The fastest we reached was 48mph. You can ski faster than that down most runs in Austria or France.”

Lifestyle

When it came to après-ski, Eddie says while Glenshee’s offerings weren’t quite up to Alpine standards, he enjoyed many nights hanging out in pubs and hotels with ski centre staff.

“A lot of people congregated in local joints like the Spittal of Glenshee Hotel down the road – ski instructors, lift attendants, piste bashers and holidaymakers,” he recalls.

“There was a little community there. You always had somewhere to go to chat to people and have fun.”

On days off, Eddie loved “being a tourist” taking trips to Braemar and Blairgowrie, exploring the Cairngorm countryside and popping into coffee shops.

He returned to the Perthshire slopes in 2018 to film an episode of Countryfile for the BBC.

It was “one of the best days” he’d ever experienced at the resort, with “beautiful clear blue skies” and perfect skiing conditions.

Ski obsession

Eddie first strapped on skis during a school trip to Italy aged 13.

He was instantly hooked and spent all his free time at Gloucester dry ski slope where he did crazy tricks like bouncing over bumps and jumping over people.

Although driven by danger and excitement, he learned to ski properly and had ambitions to represent Great Britain as a downhill skier in the Olympics.

After working a season at Glenshee, he headed off to the international ski circuit.

Strapped for cash and with no sponsors behind him, it was a major struggle.

Ultimately, he needed to find something cheaper to do or go back to plastering in the UK with his dad.

An epiphany came while he was in Lake Placid, New York, when he spotted ski-jumpers flying through the air.

“I asked if I could have a go and started ski jumping, which was a lot cheaper than Alpine ski racing. It was an economic decision really.”

Scraping food out of bins

Eddie continued to eke out a meagre existence.

“It was hard because not only did I have to learn the ski jumping technique, jumping further and getting better, but I also had to think about where my next meal was coming from,” he says.

“Very often, I didn’t have enough money so I’d go to the supermarket and buy a loaf of bread to eat.

“Sometimes a slice of bread would be what I ate that night. I just did the best I could with what I had, which wasn’t very much.

“I’d use any money I had from plastering with my dad to go as far as I possibly could.

“If that meant sleeping in the car, sleeping in cowsheds, sleeping in barns, sleeping in mental hospitals, scraping food out of bins and getting odd jobs here and there, that was what I’d do.”

From shovelling snow to scrubbing floors, there wasn’t anything Eddie wouldn’t do to indulge his passion to jump. He was a man on a mission and nothing would stop him.

Following one botched landing, he continued with his head tied up in a pillowcase to keep a broken jaw in place.

Unable to afford decent ski equipment, he borrowed what he could, wore six pairs of socks because his boots were too big and often had his helmet tied on with string.

While he was training in Finland, Eddie found himself with nowhere to stay.

He became friends with a ski jump trainer who had a part-time job as a painter and decorator and was renovating a wing of the nearby mental hospital.

“He asked if I could stay there and I was able to sleep in one of the cells for five weeks.

“While I was staying there, I got a letter telling me I’d been picked to go to Calgary so I got out the mental hospital, flew home, got my Olympic uniform and off I went!”

Snobbery

As a young working class lad competing in the world of privileged posh folk, Eddie faced crushing snobbery and ridicule.

He faced jealousy, too – he was self-taught and had been jumping less than two years while his rivals had been at it since they were in nappies.

“I met plenty of snobs and old farts who tried to undermine me but I never let it affect me,” he says.

“Some would say I shouldn’t be there, that I wasn’t even an athlete.

“But if anyone didn’t like what I was doing, it was their problem. I never let any negativity get in the way.”

Fear

It takes guts and guile to even consider performing a ski jump but Eddie admits he is “always fearful”.

“A lot of people think I’m just reckless in that I don’t think about the fear, the dangers, the consequences, but in actual fact I do.

“I know every possible, conceivable thing that could go wrong and then I assess the risk and whether it’s worth taking. You start with small jumps and build up to big jumps. It’s just like anything, really.”

The movie

Almost two decades after it was first mooted, a biopic about Eddie’s life was released in 2016, starring Taron Egerton as the main man and Hugh Jackman as coach Bronson Peary.

Eddie was initially worried the film would turn him into an “object of ridicule”.

But he was delighted with the end product and has watched it “at least 90 times”.

“It’s about 80% true and I think they did an excellent job with the film,” he says.

“It brings a tear to my eye every time I watch it.

“There’s so much more they could’ve included, though, like the scraping of food from bins and sleeping in the Finnish mental hospital. But maybe they’re keeping that for a sequel!”

Broken bones

In the 20 months between Eddie picking up ski jumping and competing in the Calgary Winter Olympics, he put his body through tremendous trauma.

“I fractured my skull twice – even though I was wearing a helmet – and I broke my jaw, smashed my collarbone, broke three ribs, damaged my kidney and knee.

“But the worst accident I had was a broken back when I was racing in Italy aged 18.

“I learned from my mistakes and made sure I never made them again.”

Celebrity status

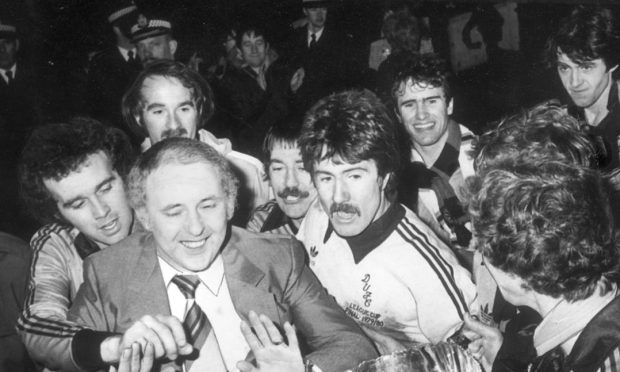

After Calgary, Eddie – who held the British ski jumping record from 1988 to 2001 – emerged more famous than any other competitor.

His shy, cheery British humour and unstoppable determination had endeared him to the world.

He threw himself into all sorts of celebrity odd jobs with the same abandon that had inspired him to launch himself off death-defying platforms.

He opened shopping centres, judged beauty pageants, was shot out of circus cannons and dressed up as a chicken to open a tourist office in Devon (they couldn’t find an eagle costume).

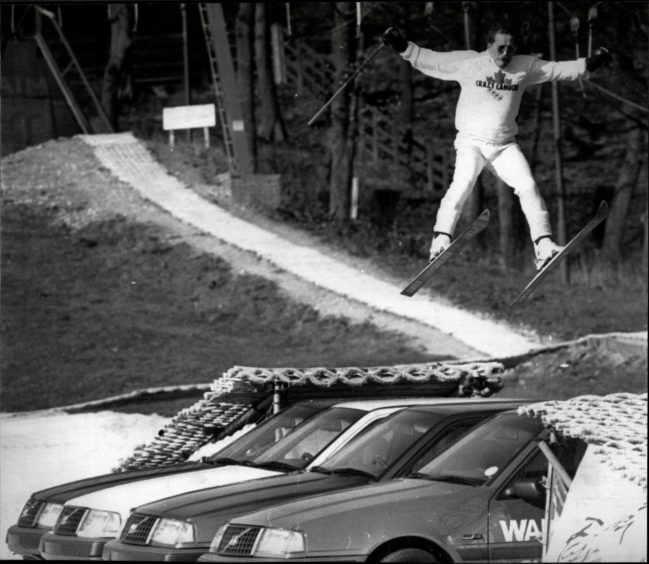

In 1995, he set an unofficial world record for stunt ski jumping after launching himself successfully over 10 cars.

He even tried his luck in the world of pop music, recording two singles celebrating his Olympian feats.

The follow-up ballad, titled Mun Nimeni On Eetu (My Name is Eddie), was composed in Finnish by protest singer Antti Yrjo Hammarberg, better known as Irwin Goodman.

Eddie sang the song in Finnish, even though he had no idea what it was about.

It reached number two in the Finnish pop charts.

At the height of his fame, he sang in front of 70,000 people at a rock festival near Helsinki.

Bankruptcy

Rich beyond his wildest dreams – he earned more than £500,000 the year after the Olympics and could command £10,000 an hour to open golf courses or shopping centres – Eddie stashed his cash in a trust fund.

When the trust went bust in 1991, he declared bankruptcy and sued the trustees for mismanagement.

Eventually, he won a settlement and pocketed around £100,000.

Wisely he’d never given up his career as a plasterer and was able to get ad-hoc work in the building trade while promoting his alter ego of Eddie the Eagle wherever he could.

The legal battle inspired Eddie to do a law degree at De Montfort University in Leicester at the age of 40.

After graduating in 2003, he returned to building and plastering, finding it gave him the flexibility to continue his lucrative PR work.

Lockdown

Despite having skied for more than 40 years, Eddie claims he’s “not a very good” skier.

“But I’m just as excited to put on a pair of skis now as I was 40 years ago! I still love it.”

With ski centres closed thanks to lockdown, the divorced dad-of-two hasn’t been able to indulge his great passion much.

He enjoyed a ski holiday in Italy last February and, after having four trips abroad cancelled, he spent a lot of time at his local dry slope last year.

“If it gets too much faff to ski in Europe with Covid and Brexit, you’ll maybe see me at Glenshee much more often in the future!” he says.

“I have such fond memories of it and I’d love to go back and ski there.”

Meantime, he’s enjoying the “isolation” of lockdown which, he says, has given him a chance to breathe.

“Since the film was released and until the beginning of 2020, when Covid happened, I was doing between eight and 12 speeches a week all over the world – cruises, conferences, dinners and lunches. It was a whirlwind that never stopped.

“It’s actually been a bit of a breather and I’ve been able to get on with renovating my house.

“I’ve always got a Plan B and C. If things don’t pick up, I might go back and do a bit of learning.

“I might do a computer course. There are plenty of things to be getting on with.

“Hopefully I’ll be ski jumping in Scandinavia in July. Until then, it’s about keeping fit and healthy.”