The hidden history of Dundee’s jute industry is explored in a new exhibition at the V&A. Gayle Ritchie finds out more.

Known throughout the world as ‘Juteopolis’, Dundee was once the world capital for jute, with the industry providing employment for more than half the city’s workforce.

Now a new exhibition at V&A Dundee explores how the booming industry was built on colonial links between Dundee and what was then British-ruled Bengal, and looks at the experience of workers in Bangladesh and India.

Artist, curator and writer Swapnaa Tamhane’s work, The Golden Fibre, shares the name given to jute because of the huge profits that could be made from the raw fibre – although those profits were rarely shared with workers in Dundee or Bengal.

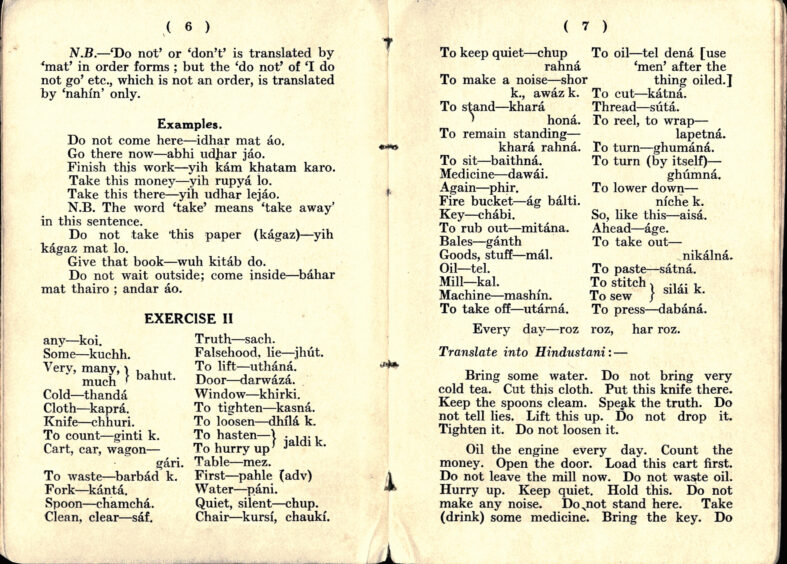

Created after Swapnaa explored the jute industry archives held at the University of Dundee and Verdant Works, it’s partly inspired by a Hindustani language exercise book used by Scottish supervisors to control workers in the Bengali mills, which includes orders such as ‘hurry up’, ‘keep quiet’, ‘do not waste oil’ and ‘do not make any noise’.

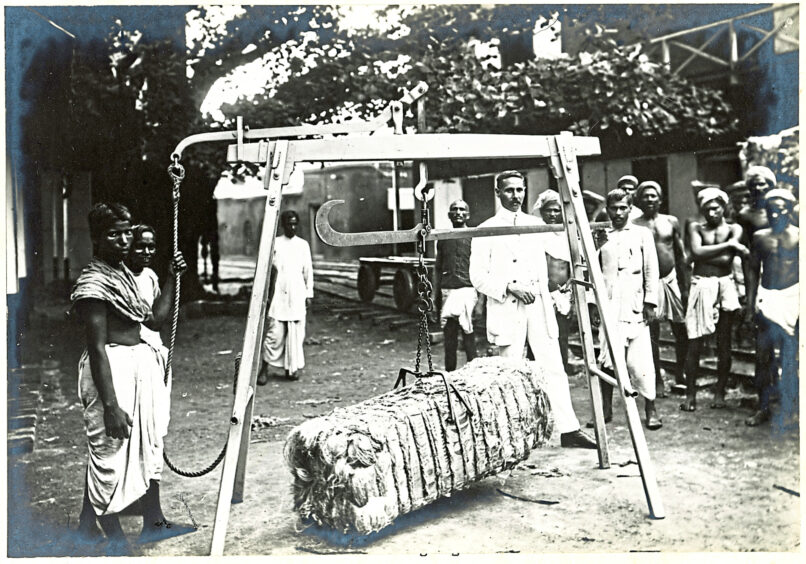

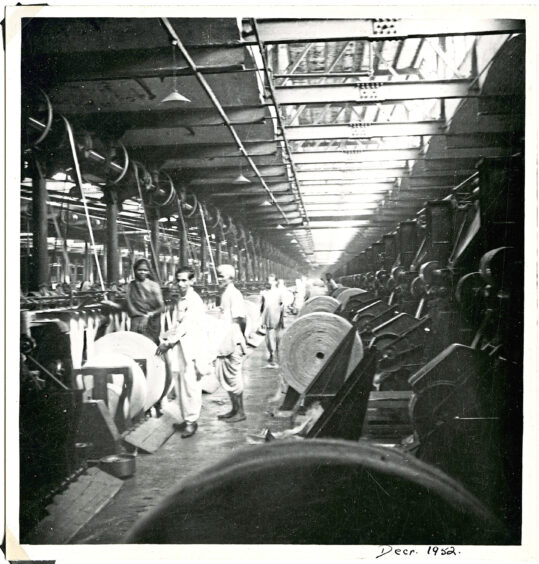

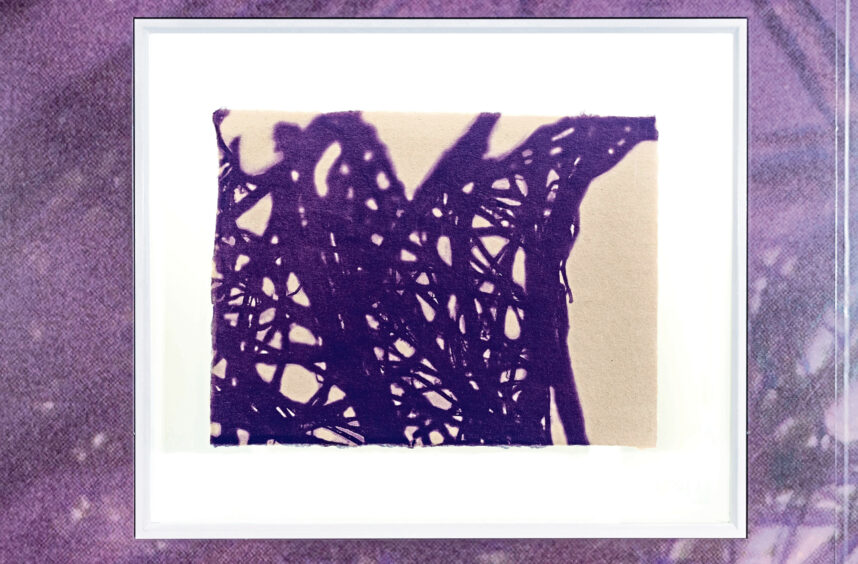

Swapnaa’s work also features a collage including archival photographs and drawings of female jute mill workers, as well as microscopic images of jute paper that she made by hand.

This laborious process involves cutting up jute cloth, soaking it in the caustic chemical lye, then beating it in water for hours to create a pulp that is then shaped and dried into rough sheets of paper.

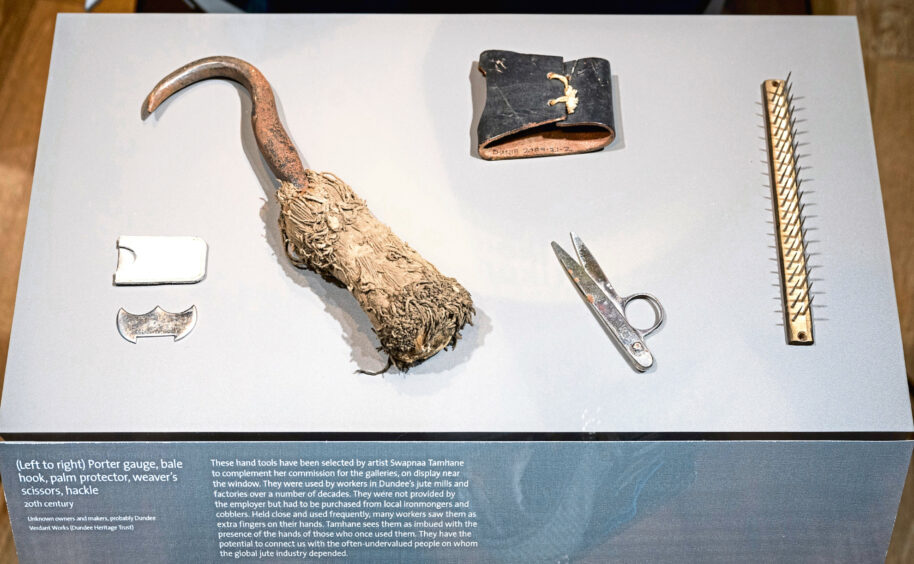

The new exhibition at the museum’s Scottish Design Galleries also includes hand tools used by mills and factory workers, such as a bale hook, hackle, porter gauge and pair of weaving scissors.

Jute capital

Dundee capitalised on its history of weaving, whaling and shipbuilding to become the world’s jute capital in the 19th Century, with products made in the city, including bagging and sacks, used to transport cotton, grain, sand, coffee and wool all over the world.

At one point, around 1900, more than 40,000 families in Dundee were dependent on the industry for their livelihoods. But by the early 20th Century, Calcutta had overtaken Dundee as the dominant centre for the production of jute.

“I wanted to focus on the lives of women in the Bengali jute industry – some of them were widows, some were fleeing their homes, some were supplementing the household incomes,” explains Swapnaa.

“Most of the women who worked in the fields to harvest raw jute were undocumented as part of the workforce. The archival images I came across are precious traces of their lives, about which we know very little.”

Inspired

Swapnaa, who works between Canada and India, became inspired to explore the history of jute when she discovered Dundee was a main producer of the textile.

“I took a trip over and spent a day at the archives at the Uni of Dundee, looking at some of the photographs and records, including accident reports,” she says.

“It was amazing to me to see that in Dundee there were a lot of photos of female employees who worked in the mills, but in India it was primarily male employees.

“Then I started reading about how women were really integral to the industry in India, so that piqued my interest in terms of wondering where those images were, and where those stories were.

“I was really curious about why the jute industry sort of died during British colonialism. The industry in India grew and wiped out what was happening in Dundee.”

Swapnaa says she found language exercise books given to Scottish mill managers learning Hindustani to be illuminating.

“These revealed they weren’t learning about the culture – they were just learning how to manage people,” she reflects.

“All the phrases learned were imperatives – ‘do this’, ‘do that’, ‘be quiet’, and so on.”

Considered ‘deviant’

She also explored how women who didn’t “fit the bill” – those who didn’t get married and have a family, or those who were widowed and abandoned – were considered “deviant” by British laws and in Indian culture.

“Some of these women were fleeing their homes and considered deviant, perhaps because their husbands were alcoholics, or because they had been abandoned by their husbands, or widowed.

“I just found it fascinating that such women could be deemed deviant. It’s about loss of control over their bodies.

“I really wanted to get into their heads, and looking at some of the photos, there was something so familiar to me, as if they were family members.”

Role of the hand

Swapnaa’s work sees her thinking about the role of the hand and the handmade in relation to drawing or making paper from either cotton or jute.

“I am curious about how this may connect me to the hands of many others across continents who have harvested, processed and manufactured these materials over centuries,” she says.

“After the paper is pressed, I put handmade jute paper under a microscope and could see how the fibres bind together arbitrarily. To me, they become a metaphor for a protest against order and structure.”

Dig deeper

Meredith More, curator at V&A Dundee, says Swapnaa’s work “starts a conversation and allows us to dig deeper” into a local story with a huge transnational context.

“It opens up an important conversation about Dundee’s relationship with colonialism and how people across continents have been impacted by it, in many different ways.

“We want to work together as heritage organisations across Dundee to reconsider the relationship between Dundee and Calcutta; two cities and two populations simultaneously shaped by jute and the colonial system it was part of.

“Since 2020 V&A Dundee has reframed displays and interpretation in the Scottish Design Galleries to acknowledge that much of Scotland’s design history is built upon the exploitation of enslaved and colonised people around the world.”

Link and divide

Mel Ruth Oakley, curator at Dundee Heritage Trust, which runs Verdant Works, has enjoyed working with V&A Dundee and Swapnaa on the project.

“It’s been a brilliant opportunity to talk about our objects in new ways and consider the ways they both link and divide those who worked in the jute industry, both in Dundee and the wider context,” she says.

“Through this linking of heritage organisations in Dundee we have been able to open conversations about the jute industry and the people connected with it in ways we haven’t before.”

Role of archives

Caroline Brown, archivist at the University of Dundee, adds: “This work demonstrates the important role of archives in helping us revisit the past and revealing narratives that have been lost or never told.

“The jute collections held by the University of Dundee were primarily created by owners and managers but we can still catch glimpses of the lives of ordinary workers in Dundee, Bangladesh and India. This is an opportunity to retell those stories and to consider their significance today.”

The display is available to see for free as part of V&A Dundee’s Scottish Design Galleries. It has been curated by V&A Dundee and Mother Tongue, a curatorial practice based in Glasgow, who are also developing a programme of complementary content and events.

The work has been supported by V&A Dundee and the Ontario Arts Council.

- The commission will be on show until the end of the year. For more information see vam.ac.uk

Conversation