Sitting on a log by the edge of the field in Strathardle near Kirkmichael, I watched a small group of swallows zip this way and that over the insect rich pasture.

It was overcast, but the air was warm and humid, and the swallows were clearly finding plenty of food. They are such stunning birds with their iridescent blue-sheen plumage combined with deep chestnut throat patch and long tail streamers.

But it is their energy and agility that is most striking and I couldn’t help but wonder how many insects a day a swallow needs to consume to fuel this frenetic life. There were some young birds around too, easily identifiable by their stubbier tails.

I’m fond of this part of Perthshire, a mixture of field, moor and woodland. Over the years, on the path up to nearby Glen Derby I have found palmate newts in puddles by the track, listened to the ‘yodelling’ of green woodpeckers and watched merlins near remote Loch Broom.

But I wasn’t in the mood for a long trek and this was a day to take easy; a day where the swallows would take precedence, so, I sat and watched them for a while longer.

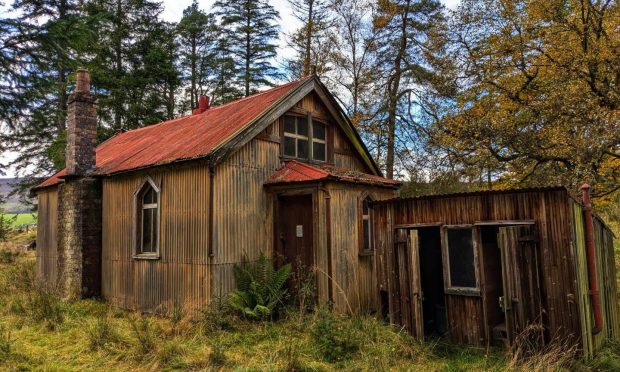

Although I couldn’t determine where, nearby there would almost certainly be some old barn or outhouse holding their little cupped mud nests. And therein lies their deep-seated attraction, living amongst us and being part of our fabric since at least Neolithic times; a benign and welcome friend.

They are pretty determined birds too. When I lived in a remote cottage near Peebles, swallows nested in my garage despite the swing door being closed and windows firmly sealed. But such was their skill and agility in the air, they were able to fly at high speed through a small gap in the door frame without touching the sides.

But it is not just the buildings that swallows adore, it is our way of life too, in particular the open spaces created by farming, especially pasture land where airborne insects abound. It is for all these reasons that swallows have become so deeply entwined within our folklore – for example, to destroy a swallow’s nest or kill a bird was widely believed to bring bad luck.

There was also much head scratching as to where the birds went in winter. Gilbert White, the eminent 18th Century nature diarist, whilst believing that some swallows may migrate, was not alone in his contention that many also hibernated in ‘holes and caverns and do, insect-like and bat-like, come forth at mild times’.

Given our scant knowledge of wildlife at the time, such a conclusion seems an entirely reasonable one to make and certainly more plausible than had he hypothesised that the dainty swallow migrated 6,000 miles to the furthest end of Africa – a journey that would have taken a sailing ship of the time many weeks to complete.

Info

Most swallows will depart to their wintering grounds in southern Africa during September. Before departing south, huge numbers often gather and roost together in reedbeds.