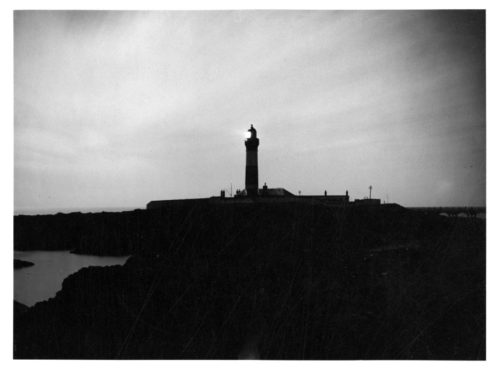

A lighthouse at night has always been a welcome sight for weary, storm-beaten mariners, navigating the challenging, craggy coastline to the safety of shore.

Scotland is home to some dramatic and spectacular shorelines, but even the most serene seas can turn on experienced sailors when a stormfront sweeps in.

For centuries, light has been used to lead seafarers to safety.

Before proper harbours existed, primitive clifftop fires acted as a beacon to mark entrances to makeshift ports.

But it was the 18th century that saw the evolution of the slender and solitary structures we are more familiar with today.

As shipping became more sophisticated, so did the infrastructure required to support it.

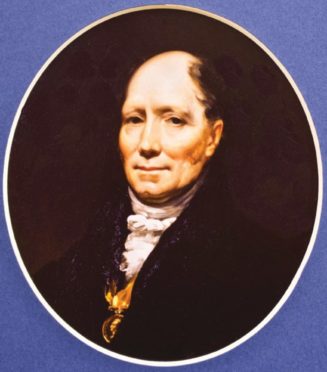

Scottish civil engineer Robert Stevenson designed and built lighthouses between 1797 and 1843, improving on English engineer John Smeaton’s invention.

Stevenson built lighthouses on dangerous rocky outcrops, pioneering new construction techniques as well as intermittent flashing lamps, giving each lighthouse its own distinct call signal.

His most famous work was the construction of the Bell Rock lighthouse off the Angus coast, which thanks to its innovative masonry work has stood steadfast for more than 200 years.

It remains the world’s oldest working sea-washed lighthouse, but Stevenson also had a hand in many of the north-east’s lighthouses.

Kinnaird Head Lighthouse

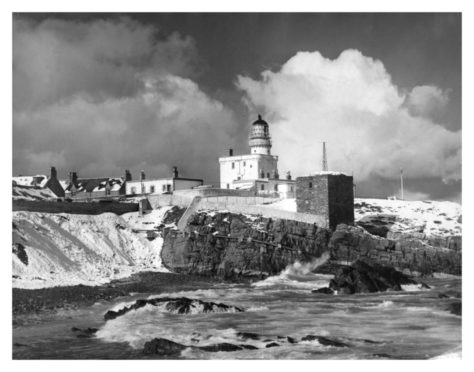

The original Kinnaird Head Lighthouse was established as far back as 1787 and was the first to be established by the Northern Lighthouse Board.

It operated solely as a fixed light, running on whale oil, about 120ft above sea level on the corner of a 16th century castle.

The earliest keepers were hand-picked for the role by Stevenson himself, he knowing only too well the conditions in which they would be expected to live and work.

A later article in the Press and Journal explained the men for the job needed to be “courageous and self-sufficient” to cope with “a curious life of combined isolation and intimate proximity”.

The first keeper of the light at Kinnaird – and indeed Scotland – was a man named James Park, a former master mariner, who received an annual salary of £30.

He was told that he and his family had to live beside the light wherever possible, with crofts nearby, but it wasn’t until Stevenson remodelled the lighthouse in 1824 that saw the installation of a new lantern and keepers’ accommodation.

But the 200-year vigil of keeping Kinnaird’s lights burning ended in 1991 when the lamp was extinguished for the final time.

It was a time of great sadness as the historic structure was replaced by a newer lighthouse nearby – not least for its last keepers Sam Wilson and Ernest England.

The pair had each spent quarter of a century illuminating the coastline and lamented that the tower’s steps would fall silent for the first time since James Park’s days.

But there was hope when campaigners lodged a proposal to turn Kinnaird Head into Scotland’s first lighthouse museum.

The bid was successful and since the 1990s, visitors have been able to learn about the solitary lives of lighthouse keepers first hand at The Museum of Scottish Lighthouses.

The lantern has been lit twice since the lighthouse was decommissioned in 1991: for the Queen’s Diamond Jubilee in 2012 and later that year in celebration of Kinnaird Head’s 225th anniversary.

Buchan Ness Lighthouse

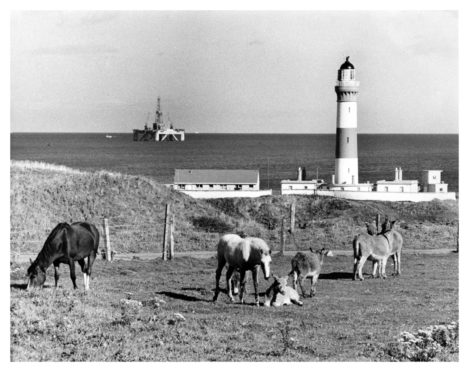

Buchan Ness Lighthouse marks the easternmost point of the Scottish mainland, built on a small island connected to the mainland at Boddam by a bridge.

In 1819, people petitioned for a lighthouse at Buchan Ness – also spelled as Buchanness – a busy trading and whaling location where ships routinely ran aground.

As engineer to the Northern Lighthouse Board, Robert Stevenson answered the call.

Stevenson chose the location and work on the granite structure began in the 1820s.

It was finished by 1824, and in 1827 was the first lighthouse in Scotland to have a flashing light.

An Aberdeen Journal report in 1826 said: “The commissioners of Northern Lighthouses have just finished the masonry of a splendid lighthouse on Buchanness, from a design by Robert Stevenson esq, their engineer.

“This lighthouse consists of an elegant tower, built of granite 122ft high, the top of which does great credit to the engineer.”

The oil lamp was so revolutionary that mariners had to be warned of the “novel twinkling light resembling a star of the first magnitude”.

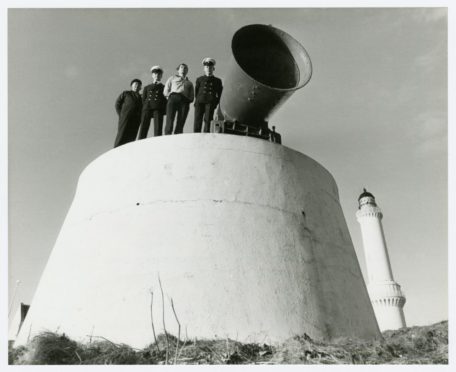

At the turn of the 20th century, a plea was made for the installation of a foghorn as an additional safety measure.

One account told how in thick fog, young women would stand behind the lighthouse beating basins with spoons to ward boats away from the treacherous rocks.

The wish was granted in 1904 and for many years the ‘Boddam Bear’ helped guide ships in poor visibility.

And in fairer conditions, to help passing vessels identify the location, a red band was painted around the white lighthouse in 1907.

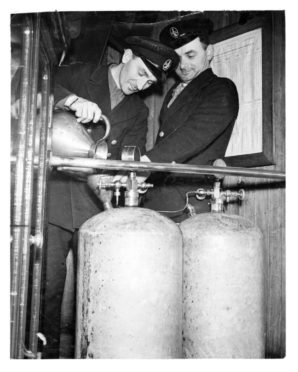

The lamp was still hand-lit as recently as 1977 before the lighthouse was electrified the following year.

But the lonely days of lighthouse keepers were numbered when the grade A listed structure was automated in 1988.

The last couple to inhabit Buchanness were Jimmy and Margaret Aitken who upon leaving the lighthouse service retrained as teachers.

Jimmy as an English teacher at Peterhead Academy and Margaret as a primary teacher at Clerkhill Primary.

Buchanness remains a functional lighthouse, but its keepers’ cottages are now holiday accommodation.

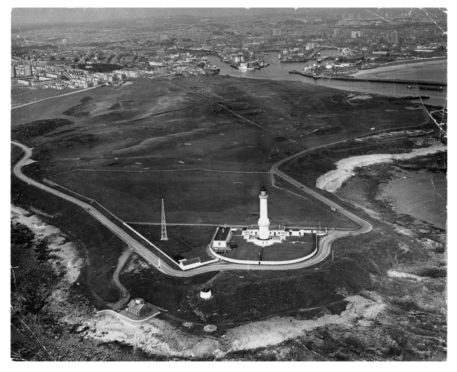

Girdleness Lighthouse

The loss of many lives on the approach to Aberdeen Harbour saw the calls for a lighthouse nearby answered in 1833.

Girdleness – also known as Girdle Ness – Lighthouse was another Robert Stevenson design constructed by Aberdeen builder James Gibb.

It featured a new, innovative double light which the secretary of the Northern Lighthouses explained sat “one over the other; but to the distant observer the lights will appear as one, having an elongated form”.

The oil-powered lights – often using oil from sperm whales – was placed in lanterns with reflectors which would project the beam 16 miles out to sea.

A refurbishment in 1847 saw the old dome replaced making the lighthouse “more useful and beneficial to the mariner”.

The improvements were timely, as Queen Victoria and Albert steamed into Aberdeen Harbour, rounding the Girdleness Lighthouse one evening in 1848.

Harbour authorities were taken by surprise when telegraphed by Girdleness to say the royal couple had arrived a day early.

In 1870 the lighthouse became a trial one for the use of paraffin instead of oil, but like the others was electrified in the 20th century before the light became automated in 1991.

Much like Buchan Ness, there was a need for a foghorn during inclement weather.

The low, baying warning of the Torry Coo could be heard across Aberdeen until it was silenced for good in 1988, replaced with a new radar system.

Rattray Head

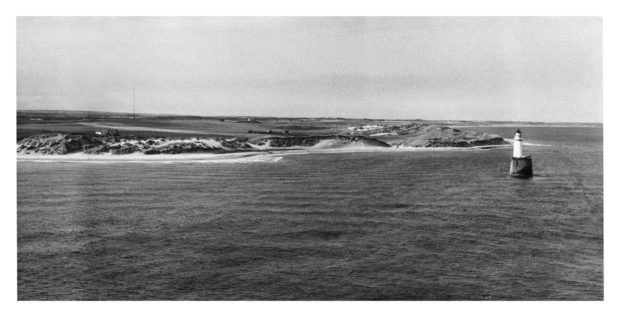

Rattray Head Lighthouse on the north-easternmost point of the coastline came into operation on October 14 1895, illuminating a particularly bleak part of the shore.

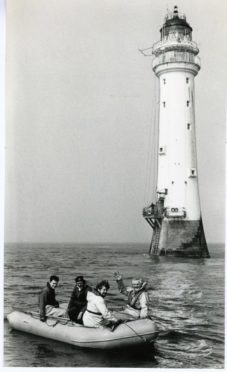

Standing guard over some of most deadly reefs and roaring breakers, Rattray Head was of a more unusual construction than some of its contemporaries.

Although it is located a short distance offshore – accessible by a causeway during low tide – it is considered one of the most ferocious parts of the north-east coast.

In winter, the lighthouse – surrounded by the shadows of shipwrecks – was often inaccessible for several days at a time.

The lonely lighthouse stands atop a manmade dressed granite rock tower, with the entrance door accessed by a terrifying 32ft climb up an iron ladder.

The lower part of the structure contained a fog horn and engine room, while keepers’ accommodation and the all-important lantern were above.

When it was first lit, the lantern had a candlepower of 44,000 compared to Buchan Ness’ 6,500CP luminosity.

The lantern was still paraffin lit and operated by principal lighthouse keeper Jack MacLean, assistant keeper Ralph Brown and their colleagues as late as 1978.

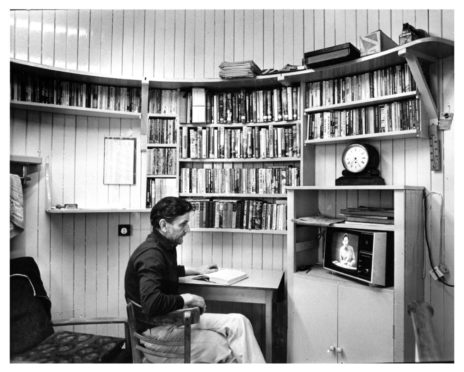

Although the lighthouse itself had not changed much in its 83 years, the keepers of the 1970s enjoyed more home comforts that their predecessors.

The six cosy and curved wood-lined rooms were furnished with books, a radio, a TV, telescope and a small kitchen, and described as “a strange amalgam of the domestic and the maritime”.

Above their heads, the lightroom contained giant glass lenses, and the original, delicately balanced clockwork mechanism to make the light flash.

The light, which the keepers kept topped up with paraffin, was extinguished between sunrise and sunset.

But the duties didn’t end at daylight – the light room needed constant cleaning and the lens polishing to ensure the lighthouse was as efficient as possible.

During poor weather when the foghorn was in operation and bellowing every four minutes, Ralph admitted sleep was an “impossibility”.

The lighthouse keepers were withdrawn when Rattray Head was automated in 1982, but the tower continues to stand like a single chess pawn in the sea warning ships of the dangers below.

And now, the lifesaving lighthouses of the north-east have inspired a sculpture trail to “shine a light on” region and raise funds for Clan Cancer Support.

Find out more about the exciting art trail and how to join in here.

See more like this: