Fife and Tayside have always been proud of their train services; and why wouldn’t they be, given the regal majesty of the Forth Bridge, the most famous structure of its kind in the world.

Hundreds of thousands of passengers used the railways to spend summer holidays in places such as Leven, Burntisland, Kinghorn and, further along the north east route, sampled the delights of St Andrews, Arbroath, Carnoustie and Montrose.

Whether sunbathing, beachcombing or golfing, many of these places relied on visitors arriving in large numbers every year.

Sadly, though, the infamous Beeching Report swept away virtually every Scottish branch line in the 1960s.

Conventional wisdom at the time viewed these losses as regrettable, yet inevitable, in an era of growing affluence – and foreign package tours – and rising car ownership.

But David Spaven was among the many people who loved travelling on the rail rather than the road – and his newly-published analysis of Beeching’s flawed approach to closures, where profitability trumped popularity, has unearthed strong evidence of a stitch-up in the way the report ignored the scope for sensible economies which could have allowed a significant number of axed routes to not only survive, but prosper.

And these included lines to Crail, Crieff, Leven and St Andrews.

Many people’s worst fears were confirmed on March 27 1963 when the prosaic headline “Distribution of passenger traffic station receipts” showed that every station between Leven and St Andrews fell into the lowest revenue category.

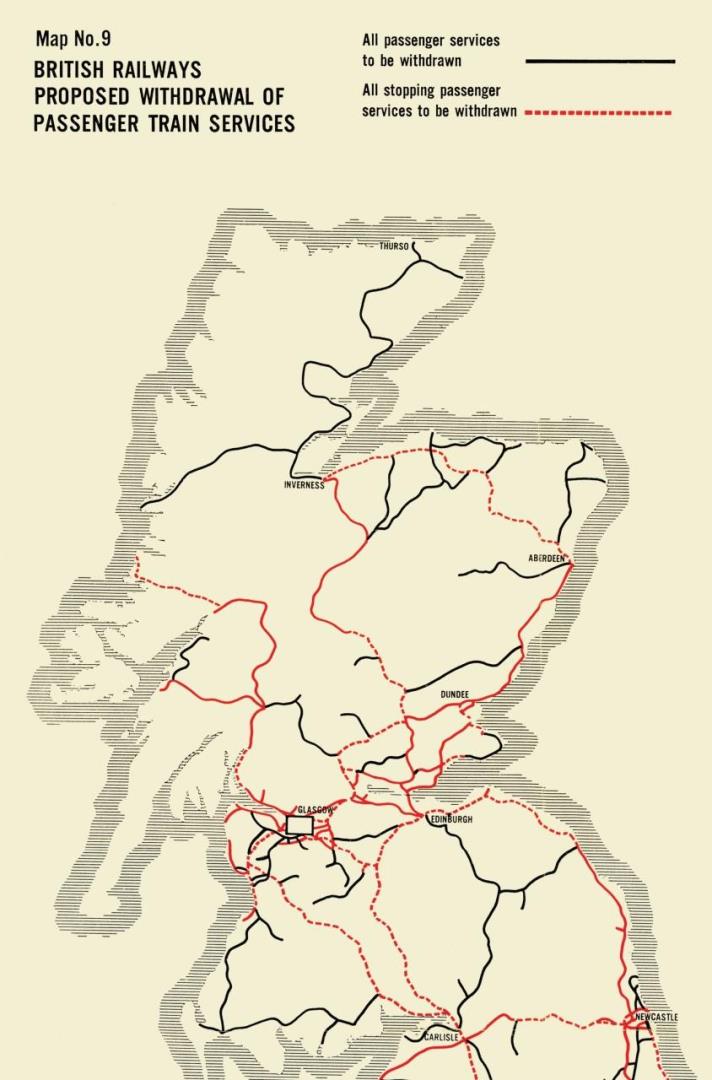

And it was therefore no great surprise when Beeching’s infamous “Map 9” – the proposed withdrawal of passenger train services – indicated the axe would be brought down on so many places across the kingdom.

‘We have to fight this decision’

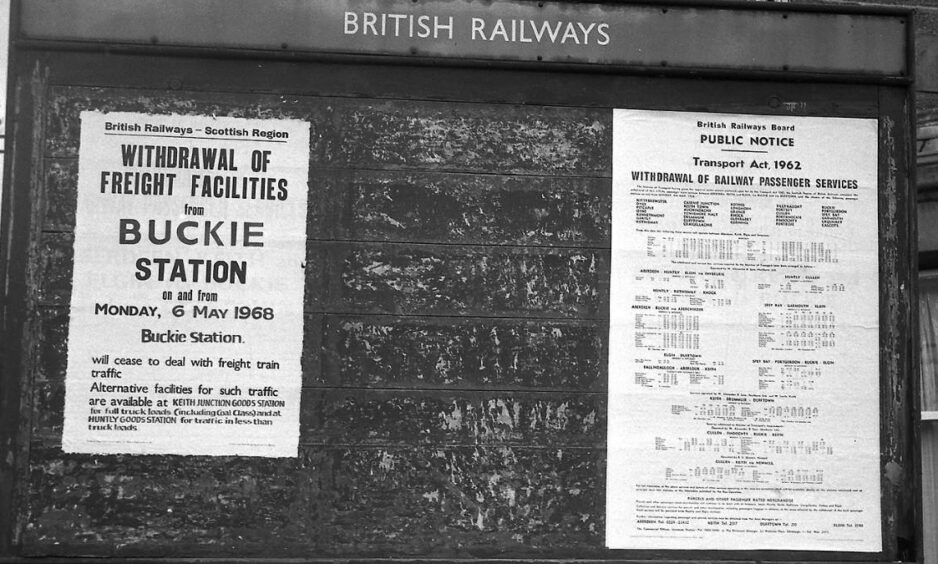

Mr Spaven said: “The formal closure proposal notices for the withdrawal of trains between Thornton Junction and Dundee via Crail (but leaving St Andrews and Leven stations unscathed) were posted in local newspapers and at the stations affected on September 2 1963 – part of a ‘second wave’ of Beeching closure proposals to be published in Scotland.

“There was a quick reaction, locally. With the exception of the St Andrews Town Council, who adopted a rather disinterested position, the response of the local authorities was swift and vociferous and the Five Burghs Committee resolved they would fight the proposals all the way and that “every possible protest should be lodged by the people living between St Andrews and Leven”.

The Dundee Courier was among the newspapers to object to the sweeping nature of the cuts, accepting that some of the services were not widely used during the winter months, but offered “a valuable source of income for the local tourist industry from April and May to September every year”.

The ‘camping coaches’ were popular

British Rail confirmed this by releasing figures which showed that passenger numbers almost doubled on “summer Saturdays – when additional trains ran in the morning and afternoon” – and they agreed the East Neuk had long been attractive for holidaymakers and the line itself hosted three ‘camping coaches’ at Elie, Lundin Links and St Monans.

These were old passenger vehicles, no longer suitable for use in trains, which had been converted to provide basic sleeping and living quarters at a variety of static locations in rural or coastal areas – and there were more than 30 such coaches sited in Scotland in 1957.

Mr Spaven, a lifelong railway enthusiast, pointed out that BR was offering opportunities for those on vacation to use these facilities in the 1960s, even after Dr Beeching had published his controversial recommendations.

The company’s 1963-64 timetable for Scotland advertised the opportunity “for carefree holidays in a coach which was fully equipped with crockery, cutlery, table linen, blankets and bed linen, and accommodates six persons”, but it was also made clear that guests had to purchase return rail tickets “from their home station to the station serving the camping coach.”

It sounds like something which could be revived even now, but there was no similar enthusiasm for such far-sighted ideas in the Swinging Sixties.

On the contrary, despite the campaign by the public, the press, and intervention from local authorities, the BR management’s response to the suggestion that the East of Fife railway had been insufficiently developed and promoted – “over the years, much effort has been put into trying to persuade the public to make use of rail facilities” – showed they had thrown in the towel.

And, while there were discussions between the relevant parties, including BR, the unions and representatives of the East Neuk burghs and Sir John Gilmour, the MP for Fife East, they hit a brick wall as the summer progressed and the final throw of the dice was a meeting in Glasgow on July 30 when Gilmour expressed his fears that “Leven would only be a temporary railhead and, within a couple of years, the station there would also be facing closure”.

As Mr Spaven said: “He was right. And the meeting was not a success. The final day of service was Sunday September 5, bringing the last day-trippers from Edinburgh and Glasgow to enjoy a visit by train to the East Neuk.

“Excitement mounted all day among locals who were determined to give the line a good send-off and Alexanders put on a special bus from Leven to take those who wished to travel on the last train, the 18.20 Crail to Glasgow service, the last eastbound train having gone several hours before.

“Before 6 o’clock, the ticket office at Crail had run out of tickets and paper certificates had to be issued in their place.”

It was an evocative occasion but, as Joni Mitchell sang a few years later: “Sometimes, you don’t know what you’ve got ’til it’s gone.”

And that was certainly true for many across Fife.

Mr Spaven’s new book, Scotland’s Lost Branch Lines: Where Beeching Got It Wrong, isn’t a hatchet job on the man whose name has become notorious.

On the contrary, he has investigated a variety of different decisions which were implemented during the 1960s and concluded that Beeching has been unfairly tagged as the bogeyman of the railway bogies.

He stated: “It is not fashionable to say so but, in some ways, Beeching has had an unfair press.

“His promotion of fast inter-city services, ‘merry-go-round’ coal trains from colliery to power station and the pioneering Freightliner (container-carrying) concept took the railway in the right direction, all proving their worth in subsequent decades and continuing to do so today.”

Yet, there was nothing to celebrate in places such as Fife and Crieff and St Andrews, for those who had previously relied on these services.

Mr Spaven said: “Doubtless, most of the crowds witnessing the last train (at Leven) were no longer regular rail travellers.

“There was a nostalgic attachment to the railway but, as in many of these closures the length and breadth of Britain, not enough people had heeded the warning to: ‘Use it or lose it’.

“However, for former rail users without access to a car, there was only one alternative mode of transport, whose inadequacy was quickly demonstrated.

People soon moaned about buses

“On Monday September 6, the buses took over with a nominally hourly bus from Newport and St Andrews to Leven station.

“But, within days, public protests were being made about the poor service provided and the failure of the buses to maintain any proper connections.”

And matters deteriorated with the subsequent closure of the Leven-St Andrews service, which many had warned would happen before it did in 1969.

The line shut on October 6 and, according to the East Fife Mail two days later: “The broken clock on the platform at Leven station signalled on Saturday that time had despairingly run out… for at 8.25pm, the last passenger train left from a dark platform on its ultimate journey to Thornton.”

Mr Spaven isn’t a dewy-eyed sentimentalist.

He points out that while Fife could have been developed as a scenic route, there was no guarantee that it would have competed with “the changing face of holidaymaking and the inexorable rise in car ownership”.

But he’s not alone in wishing there had been more of a fight rather than a situation where “the government had spoken and the trains had vanished”.

- Scotland’s Lost Branch Lines is published by Birlinn at birlinn.co.uk