In a quiet corner of Dundee Howff lies an unmarked grave.

One of the last of the 80,000 burials to take place at the graveyard, it is the final resting place of a local man whose battlefield exploits were long-forgotten.

Its occupant, Gunner William Henry, died in 1853 , aged 76. Yet he had served for 13 years with the Royal Artillery, ‘over the hills and far away’ as a song of the time put it, culminating in him fighting at the Battle of Waterloo in June 1815.

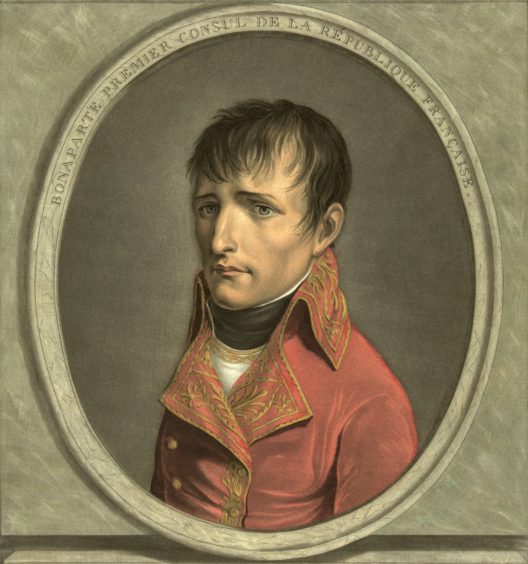

Gunner Henry thus formed part of the Duke of Wellington’s international army which finally put a stop to Napoleon’s European rampage.

His descendent David Henry, who was born in Dundee, stumbled upon the incredible tale after delving into his family history during the lockdown.

Now, David has pieced together Gunner’s story to shine a light on his bravery in the hope this unmarked grave won’t remain thus for much longer.

To begin with, David only had a few fragments to work with.

He said: “We knew that William Henry was born in late 1776 in Peterculter, just to the west of Aberdeen.

“And that he died in Dundee at the age of 76, on February 14 1853.

“Also that he was buried in the Howff. But little else.”

Unlocking a key part of the story

Many other aspects of William Henry’s life had always remained unknown until his descendent unlocked a key part of the story.

David continued: “There was one part of our research that came as a surprise, but it could be firmly established , and that was the fact that Gunner Henry took part in the Battle of Waterloo.

“We know this because we have detailed primary sources which confirm that he fought in that battle.

“They also tell us which unit he was part of – the 9th Battalion of the Royal Regiment of Artillery.”

It was this key discovery that acted as a trigger for further research into the life and times of Gunner Henry, and led David and his family to uncovering several more important documents.

David added: “Once we found these records, we were able to work backwards and fill in the rest of the blanks.

“To summarise his early life, it seems likely that William left his home in rural Aberdeenshire as a young man to seek work, and found a job as a ‘flax dresser’, in the new factories of Dundee.”

Gunner Henry joined up to fight in 1806

A common profession at the time, the flax dresser used a hackle to separate the coarse bit of flax in preparation for the bundles to be spun into a yarn.

David continued: “But Gunner Henry either left that position, or lost it, perhaps through unemployment, and signed up to join the army instead in 1803.

“He would’ve been around 27 years of age.

“He then met his future wife, they had a child, and married in 1805.

“Soon after this, he went back to the army, joining the newly formed 9th Battalion Royal Artillery in 1806.”

In the 9th Battalion, each cannon was operated by a crew of nine or ten men under the orders of their officer.

Given his rank – the equivalent today of ‘Private’- Gunner Henry would have been one of these crew men.

Each was allocated a specific drill, done by number.

David explained: “For example, crew man Number 8 might be responsible for loading the cartridge and round.

“Number 9 would insert the fuse, ready for Number 10 to light it at the right moment.

“Gunner Henry would likely have been required to complete all of these tasks at different times in rotation, or to replace casualties as needed, forming part of a tight, deadly, fighting unit.

“By tracing his company through the Napoleonic Wars, we know that he was in the thick of the battle at Waterloo, with his unit taking part in many of its crucial actions.”

But, at some point, Gunner Henry was wounded in the hip.

David said: “He could have been wounded during the defence of Hougoumont; the onslaught by the French cavalry on the British ‘squares’; or during the final attack by the massed columns of the Imperial Guard.

“We will probably never know for certain, but it is interesting to speculate on the possibilities.

“Whenever he became a casualty, it undoubtedly had profound consequences for his future.”

Gunner Henry survived the bloodshed

The evacuation of casualties was a sporadic activity.

It was either carried out during lulls in the fighting, because comrades took pity on

someone, or because they were a senior officer.

Walking wounded had to look after themselves.

So, many of the wounded who were unable to move lay where they fell, sometimes for days after the battle, or until death overtook them.

However, Gunner Henry made it off the battlefield and was evacuated back to England, where upon his return he was awarded the Waterloo Medal.

This was issued to all combatants who took part in the battle, irrespective of their rank.

David said: “It was the British Army’s first ever true campaign medal, setting a prototype for all such awards until the present.

“These were hard and often brutal times.

“We’ll never know what Gunner Henry felt as he faced the horrors of that fateful day, yet, even two centuries on, we can at least respect his courage in fulfilling his duty as one of Wellington’s fighting men.”

But his long army career was over.

What did Gunner Henry look like?

The army pension records describe Gunner Henry as being 5ft 8 1/2in tall, with brown hair and grey eyes.

He was discharged from the Royal Artillery in April 1816 due to his injury, on an allowance of nine shillings a day.

Gunner Henry was classed as an “out pensioner” so still had to find work again.

Gunner Henry returned to Dundee, and his wife, Christian and the couple had 10 more children in addition to their first child.

Both he and Christian appear in the 1841 and 1851 censuses, living in Constitution Street, described as a ‘manufacturer’ in 1841, and a ‘flax dresser’ once again in 1851.

Henry lived on for a further 37 years after his discharge from the army and his return to Christian.

He died in Dundee, in February 1853, due to inflammation in his lungs which was a common occupational hazard amongst textile workers.

Christian died just a few months after him, aged 67 years, from ‘paralysis’ and was buried in the same Howff grave on October 13 1853.

David said: “I’ve asked the city council whether it would be possible to install a small horizontal plaque as a grave marker for Gunner Henry and his wife, Christian.

“I think the last resting place of this ‘local hero’ and his life long partner should be identified.

“Marking it in this way, I think, would add to the richness and understanding of this historic place and the people of Dundee.”

By a quirk of history, and just a few yards away, near the Meadowside entrance, you can view the tomb of Jules Legrandre.

Born in Chartres, France, in 1785, Legrandre was transported to Scotland in 1812 as a prisoner of war.

Here he met and married a local lady – in March 1815 – just after news had broken of Napoleon’s unexpected return to France from Elba and the start of the ‘Hundred Days’ that led to Waterloo.

He continued to live in Scotland, earning a living as a French teacher, until his death in 1840.

David concluded: “Legrandre’s tomb is proudly and publicly inscribed with his rank as a ‘Lieutenant in the French Imperial Guard’ – the ‘Napoleonic foe’, from my ancestors’ perspective, at that time in history.

“Yet Gunner Henry has no such marker.

“What a fitting ‘book end’ to be able to also point out the resting place nearby of one of Wellington’s heroes.

“It’s tempting to think that even today the shades of William and Jules still share reminiscences of battles long past across the peaceful sanctuary of The Howff in the heart of their city.”

More like this:

Number 45544: John Fletcher was decorated Dundee soldier murdered at Auschwitz

Memorial bench to be unveiled for Perth soldier killed by IRA sniper

Auchterarder WW1 soldier’s remains may have been discovered 105 years after death at Somme

Conversation