A major new exhibition at the National Museum of Scotland in Edinburgh is looking at the history of anatomical study, from artistic explorations by Leonardo da Vinci to the Burke and Hare murders. Michael Alexander found out more from the lead curator.

When a group of boys headed out to the slopes of Arthur’s Seat in Edinburgh to hunt for rabbits in late June 1836, they made a discovery that remains a baffling mystery to this day.

Hidden in a small rock recess on the north-east side of the prominent volcanic hill, they unearthed 17 miniature coffins hidden behind three pointed slabs of slate.

Each coffin, only 95mm in length, contained a little wooden figure, expertly carved and dressed in custom-made clothes that had been stitched and glued around them.

Eight of the Arthur’s Seat miniature coffins survive to this day.

But who made the intricate carved figures? Who did they represent? Who placed them in their secret sepulchre – and why?

Link to Burke and Hare murders

The intriguing question is raised as the coffins form part of a major new exhibition at the National Museum of Scotland, Anatomy: A Matter of Death & Life, which examines 500 years of anatomical study.

From artistic explorations by Leonardo da Vinci to the social and medical history surrounding the practice of dissection of human bodies, it looks at Edinburgh’s role as an international centre for medical study.

However, it also offers insight into the links between science, crime and deprivation in the early 19th century and explores whether the miniature coffins were linked to Edinburgh’s infamous Burke and Hare murders of 1828.

“The Arthur’s Seat coffins are one of these intriguing and enduring mysteries and we will probably never know what they actually were,” says Dr Tacye Phillipson, senior curator of modern science at National Museums Scotland.

“There were 17 small coffins about nine or 10 centimetres long that were discovered by some boys up on Arthur’s Seat in Edinburgh and they contained little figures dressed.

“There’s just been speculation ever since – what were they, who put them there, why were they put there?

“And one of the enduring suggestions – because they were found in 1836, only a few years after the West Port Murders – is that the 17 coffins and the little figures represented burials of the 17 people whose bodies were sold by William Burke and William Hare.

“The 16 people they murdered and the one who’d died of natural causes.

“But it’s so long ago. All we know is the story of their discovery and that they are a very good mystery to speculate about.

“They are normally on display in the National Museum of Scotland but they have moved into our temporary exhibition and their place (in the main museum) is being held by some replica coffins that were made for the televising of Ian Rankin’s novel The Falls which features them.”

Fascination with killings

Through the lens of history, the Burke and Hare murders continue to fascinate almost two centuries on.

The series of 16 killings were carried out in 1828 by Irish immigrants William Burke and William Hare over a period of 10 months.

The corpses were sold to Robert Knox for dissection at his anatomy lectures, earning the murderers around £150 (around £12,000 in today’s money).

When the murderous pair got sloppy and the law caught up with them in November 1828, Hare turned King’s witness and, granted immunity from prosecution, he sold his old friend down the river.

At 8.30am on Christmas morning, 1828, Burke was charged with murder. On January 28 1829, he was hanged in Edinburgh’s Lawnmarket before a crowd of thousands.

The following day, his body was publicly dissected at the University of Edinburgh Medical School.

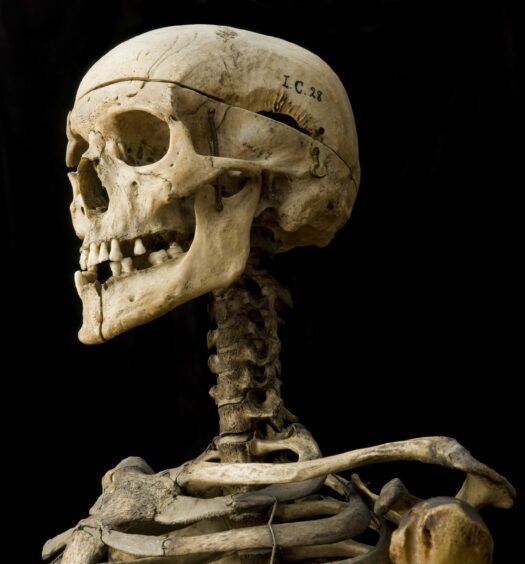

While Burke’s hand-written confession letter and the robes worn by the presiding judge at his trial are themselves an intriguing part of the exhibition, Dr Phillipson is in no doubt that one of the most resounding “real” exhibits is the skeleton of murderer William Burke himself.

“When William Burke was sentenced to hang and then be publicly dissected, the judge David Boyle, said that he hoped William Burke’s skeleton would be preserved and it has been,” she says.

“That being a real reflection of both William Burke as murderer and as the skeleton of a man who was dissected in the anatomy theatre at the University of Edinburgh is I think something a lot of people come to and find very striking in its reality.”

Punishment fitting the crime

Dr Phillipson explains that the usual sentence for murder in those days was execution followed by either dissection or the body hanging in chains for years while it decayed.

The 1752 Murder Act specifically said that the body of an executed murderer should not be buried.

It was part of the standard legal punishment for murder at the time.

However, in those days, what we now consider to be the pseudo-science of phrenology was also at its height.

While the man doing the dissection Alexander Monro III specialised in examination of the brain, phrenology tried to find an explanation for personality using what are now considered to be “completely inadequate tools for studying the brain and the shape of the head”.

Casts were taken of the head and discussions took place as to whether they did or did not fit in to expectations, at that time, of what the head of a murderer should look like.

What else is in the exhibition?

Covering five centuries of medical exploration, the exhibition looks at Edinburgh’s role as an international centre for medical study and examines the circumstances that gave rise to the murders and asks why they took place in Edinburgh.

It unpicks the relationship between science and deprivation and looks at the public reaction to the crimes and the anatomical practices responsible for them.

The acquisition of bodies was intertwined with poverty and crime, with grave-robbing – stealing unprotected bodies for dissection – becoming a common practice.

On display is a ‘mort safe’; a heavy iron box placed over a coffin to deter would-be body snatchers. Dr Phillipson explains that during the early 19th century, it was commonly known that anatomists were dissecting the bodies of dead people and that they were doing this to bodies that had been “stolen” or “simply appropriated” from graveyards.

The big reason behind this, was that dissection of dead bodies was (and still is) absolutely crucial for anatomy and for the training of medical students.

At a time when there was simply no other route to provide a sufficient number of bodies to meet this acknowledged need for medical training, the authorities, while wrestling with this question, mostly turned a blind eye to grave robbing.

The issue of protecting graves was taken up locally by friends and relatives, who would either try and keep watch at a grave yard or hire the use of an expensive mort safe which was a really heavy tough iron lock box to keep the coffin in.

At the same time, there was also widespread awareness that anatomists would pay very good money for a dead body, and that’s what triggered the West Port murders.

“There was a clear link between poverty, deprivation and grave robbing mostly on a practical level that poorer people had afforded thinner coffins and shallower graves that were close together,” says Dr Phillipson, who has an academic background in physics, has worked with the museum for 16 years and is the lead curator for this exhibition.

“There was somebody who was a grave robber in London who was questioned about this and said ‘of course I went to the paupers’ grave because for the same amount of digging I could get three bodies as from one from a fancier grave’.

“Then in 1832 when the Anatomy Act was finally passed that put an end to grave robbing.

“It did it by making available to anatomists the bodies of poor people – of people who died in workhouses, in asylums, in hospitals – hospitals in those days were charitable organisations for people who couldn’t afford home care.”

Leonardo da Vinci sketches

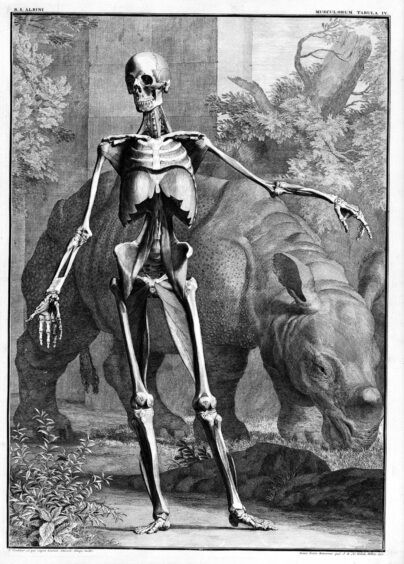

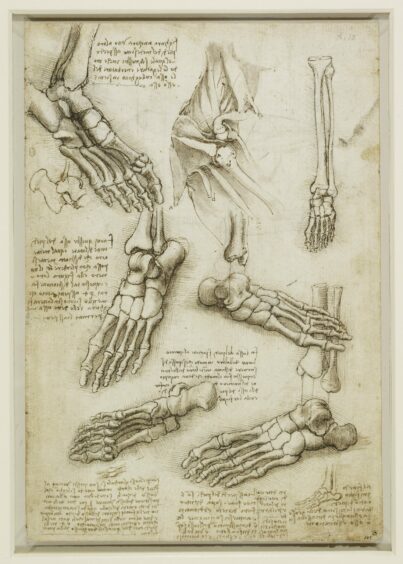

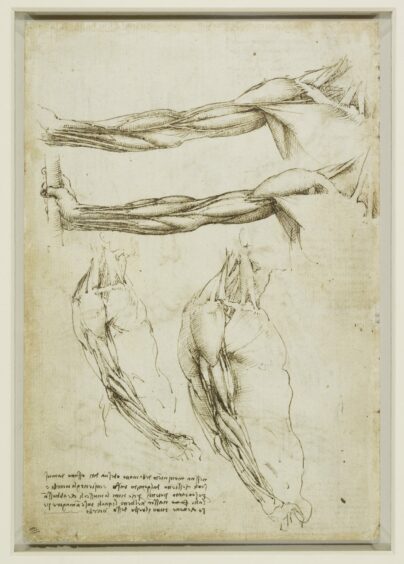

Anatomy opens with early examples of anatomical art, including sketches by Leonardo da Vinci, lent by Her Majesty The Queen from the Royal Collection.

These introduce the search for understanding about the human body and anatomy’s place in the development of medical knowledge across Europe.

The anatomical drawings by Leonardo da Vinci have attracted a lot of attention because people can get so close to them and realise these beautiful, elegant sketches showing delineation of bones of the foot were done 500 years ago.

Visitors to the exhibition, which is sponsored by Baillie Gifford Investment Managers, also find out more about the role anatomy played in the Enlightenment.

In the 18th century, Edinburgh developed into the leading centre for medical teaching in the UK, and the demand for bodies to dissect and study vastly outstripped legitimate supply.

Surgical instruments also feature. There are a number of places in the gallery which reflect on medical treatment at the time.

“One thing about the surgical instruments, says Dr Phillipson, “is that users would have benefited a lot from anatomical knowledge.

But what hadn’t been discovered yet were things like germs, anti-sceptics or anaesthetic.

Operating rapidly was therefore vital which needed a lot of anatomical knowledge.

Handles on a saw and velvet lining, for example, indicate these were not designed to be sterilised in the same way as all modern surgical instruments are.

Can models replace real bodies?

Other notable objects in the exhibition include a full-body anatomical model by pioneering model maker Louis Auzoux.

“The Auzoux model is very striking,” adds Dr Phillipson.

“It was bought new by Aberdeen University and is an illustration of both the strength and the weaknesses of anatomical teaching, without using real bodies.

“So robust, it can be taken to pieces, can be repeatedly dissected.

“But it still doesn’t replicate in the same way the knowledge gained from dissection of a real body.

“As I point out to people now when talking about how advanced computer models, artificial intelligence scans are, this is great, but also, would you want somebody doing surgery or setting a broken bone for that to be the first time they have cut through actual human skin – the practical skills of knowing how to re-set a broken joint?

“You don’t get that in the same way from a computer screen.”

Contrast with modern medicine

Viewed through the modern lens, it’s very easy to express horror at the crude methods used in the 19th century and to be grateful for being alive at a time of modern medical knowledge.

The exhibition closes by highlighting the changing practices and attitudes around body provision in the century and a half since the Burke and Hare murders, bringing the story right up to date.

It looks at the modern approach to body donation at universities in Scotland and contrasts the ethics, practices and beliefs today with those of two centuries ago.

If centuries-old dissection, research and development hadn’t happened when it did, however, Dr Phillipson says it’s clear we may not have developed the knowledge, the abilities, the skills and the expectations that underpin medical science today.

“It was vitally necessary to have the understanding,” she adds.

“For example, Leonardo da Vinci dissecting the heart and understanding how the heart worked.

“It wasn’t until the 20th century that the first operation on heart surgery took place.

“But that previous knowledge of the heart wasn’t useless because you still have a post mortem exam to explain why someone has died.

“Looking at knowledge from post mortems relating to symptoms in somebody living, you could say ‘aha you are clutching your chest in pain, I know what’s going on inside!’ and that helps with understanding.”

When to see the exhibition

*Anatomy: A Matter of Death and Life runs at the National Museum of Scotland, Chambers Street, Edinburgh, until October 30. The ticketed exhibition costs £10 for adults, £8.50 for over 60s and £7.50 for students, unemployed, disabled and Young Scot holders. Under-16s and National Museums Scotland members are free.

For more information and tickets go to https://www.nms.ac.uk/exhibitions-events/exhibitions/national-museum-of-scotland/anatomy-a-matter-of-death-and-life/

Conversation