When Monikie man Murray Hackney read a recent Courier feature about the splintered remains of the Dundee-crewed whaling ship Nova Zembla being found on a remote beach in the Canadian High Arctic, he was intrigued.

His great grandfather Captain James Bannerman skippered several Dundee whaling ships before being lost at sea during the First World War, aged 69.

Dundee-born Bannerman, who lived in Leuchars for a while, was in command of the Dundee whaling ship SS Morning when she foundered in a storm north-east of the Faroes in December 1915, while carrying arms to Russia.

Who was Captain James Bannerman?

Born in 1846, he was a registered whaling master by the age of 28.

He was master of the Ravenscraig in 1874.

He was master of the famous Dundee ship The Balaena, which inspired the Scottish sea shanty The Dundee Whaler.

He was the mate of the Terra Nova that tried to free Captain Scott’s Discovery when she became stuck in the Antarctic ice in 1904.

How common were Inuit relationships?

It wasn’t uncommon for Scottish whalers to have relationships with Inuit women while spending months at sea in the Arctic.

There had been a “rumour” in the family for years about James Bannerman doing so too.

Murray’s mother used to tell him how her grandfather would “say he was away for long periods of time and always came back smelling of fish”.

However, it was only relatively recently that Murray tracked down an Inuit relative with whom he shares Bannerman as a great-grandfather.

“Basically I remember my mother talking about her grandfather who was James Bannerman,” said Murray, 86, a former Morgan Academy pupil and retired Monifieth-based timber frame house build supplier.

“Bannerman had been up in Baffin Island and he rescued two Inuit who were dying of starvation from an ice flow.

“He took them into Pond Inlet.

“The following year this woman gave birth to a daughter.

“This was not uncommon.

“Apparently there’s quite a lot of Scottish blood in Inuits up there.

“Bannerman’s daughter had a son, Inuguk.

“That’s all I knew for a long time.

“I presumed I might have a descendent from him.

“That we shared a great grandfather.

“A cousin third time removed.

“But then my daughter Katie who knew the story mentioned a book she’d heard about on TV.

“It’s about the polar migration of the Inuit and it’s got the most unpronounceable name, Qitdlarssuaq.

“That’s when I started to learn more. It’s quite a thing!”

How did Murray find out more?

Murray started researching online.

The only copy of the book he could find was a second hand one in an American library.

He sent for it. “It cost me five quid which wasn’t bad,” he said.

One section in it was by Inuguk – the son of Bannerman’s Inuit daughter.

Inuguk’s testimony read: “My grandfather was a white.

“He was a skipper on a whaling ship.

“He stopped being captain – while still remaining some kind of chief.

“He came often into this country.

“He often arrived on one or other of the whaling boats, usually in the month of May.

“It was during this period that I was seeing him.

“As I was his grandson and as he liked me a lot, every year when he arrived he brought me pocket knives.

“I saw him regularly during my adolescence.

“It is when I had almost grown up and became a hunter that I saw him for the last time.

“He went back (to his own country) over there, far away, where he was a chief.

“When he stopped coming we thought he was dead.”

Inuit woman named after Dundee wife

Inuguk’s grandmother, with whom Bannerman had sexual relations, had an Inuit name, Uajug.

However, the Dundee whaler gave her the name Jessie Bannerman.

This was the same as his wife’s name back home in Dundee.

“I can only presume he gave that name for fun or in case he got confused!” said Murray.

“When I was growing up, and my mother talked about James Bannerman, there was no suggestion of an offspring– not that I knew about anyway.”

Finding out he had an Inuit cousin

Four years ago, and trying to find out if he had any modern day relatives in the Arctic, Murray made contact with the Canadian government.

Telling them about Inuguk and the connection with Pond Inlet, they passed him on to the government office in Baffin Island, who passed him on to another.

“I was describing who I thought might be somebody who had white people in their family someplace,” said Murray.

“I eventually spoke to somebody in the development office in Baffin Island, and they said ‘oh yes there was a guy who said he had a white great grandfather, but he’s left now. He’s retired through ill health’.

He was given the email address for Appitak Enuaraq who was born in Pond Inlet and still lives there.

It turns out this was Murray’s third cousin, also descended from James Bannerman.

“When I made contact with him, he was amazed to discover he had a cousin in Scotland,” said Murray.

“He did know a bit about his history.

“He can’t find many records there because all the history of the Inuit is word of mouth – it is never written down.

“I’ve never spoken to him on the phone or anything, but he writes perfect English and Inuit of course.

“He can remember being brought up – at that time hunting and they lived in igloos.

“And then it all changed when the Canadian government took over.

“I got the impression he wasn’t very impressed with the Canadian government.

“They were all given ‘numbers’ apparently which sounds a bit weird.”

Interest in modern Dundee

Murray corresponds with Appitak, who is “in his 60s” and has a large extended family, at Christmases and birthdays

He’s interested in Scottish things. He asked Murray recently if there’s a Bannerman tartan.

There isn’t. But with the Bannermans being part of the Forbes clan, one of these days Murray wants to send him a Forbes clan scarf or tie.

He was also interested in Dundee.

He wanted to know “what was going on and what the family was”.

“I find their way of life out there quite incredible,” said Murray.

“I said to him once ‘it’s getting warmer here, we got 18 degrees’.

“He said ‘oh it’s getting warmer here too, we got minus 10’.

“I remember him saying to me in one email they get 80mph winds.

“They just don’t let children out in those conditions because they just get blown away. Ice and snow, 80mph. It’s not survivable.

“But he has noticed global warming too.”

Despite never meeting him, Murray has seen photographs of Appitak.

He has a moustache and says it’s “difficult to know” if there’s a family resemblance.

‘White blood’ led to discrimination

Speaking to The Courier from Baffin Island, Appitak told The Courier how Captain James Bannerman was “known to be kind” and very much a part of his child’s life.

He left a strong bond with the Inuit known as Eskimos back in the day.

For Appitak himself, however, having “white” blood in him meant he faced a “lifetime of discrimination”.

“I had never seen but heard of white men as they were known by until I was about three years old,” he said.

“Being of non-Inuit meant a life time of discrimination from both my blood family and the world of white men.

“I grew up in what’s comparable to your world as third class citizen in my own world during whaling days and such.

“The fact that I had Scottish blood meant a lifetime struggle to survive.

“To me, my great grandfather was just a myth until some relatives from Dundee, Scotland, tracked me down by internet.

“I’m now having a nice relationship electronically.”

‘Summer wives’ were common for whalers

Tynemouth-raised historical climatologist Dr Matthew Ayre, formerly of the Arctic Institute of North America at Calgary University, Canada, has extensively researched the shipwrecks around Baffin Island, and rediscovered the Nova Zembla, as featured previously in The Courier.

He said it was “common” for whalers to have relations with Inuit women who were affectionately known as “summer wives”.

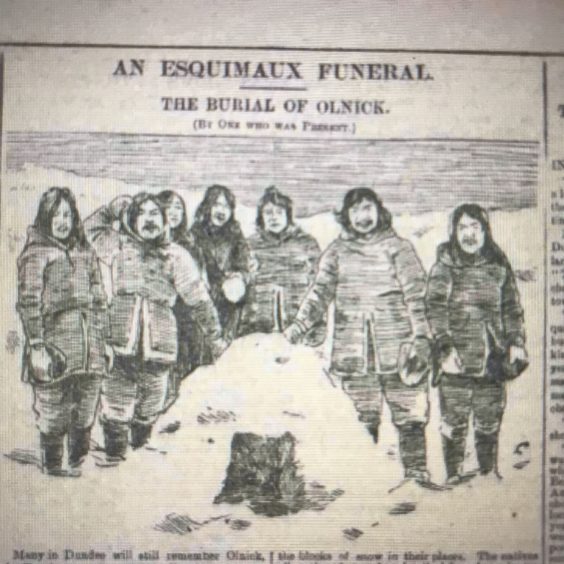

He was particularly fascinated by the story of Olnick – also previously featured in The Courier – who was well known to Dundee whalers and who eventually agreed to let him accompany them home to the city.

“Most people I’ve had the pleasure of meeting up on Baffin Island have some relationship back to Scottish whalers,” said Matt.

“Bannerman features prominently in the knowledge of descent and his name appears to be the most remembered.

“I don’t have a reason as to why his name endures in memory.

“But he was one of the last to visit regularly before the trade ceased.”

Dundee at forefront of whaling

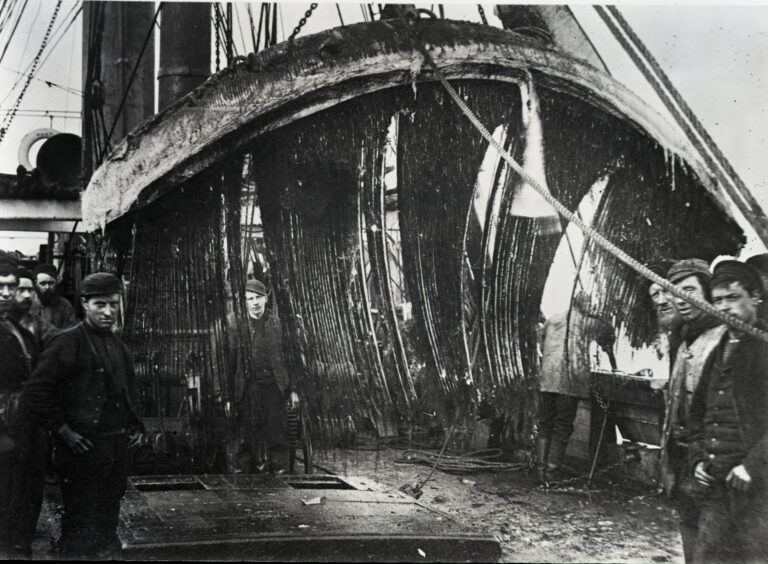

Between the 18th and 20th centuries, Dundee whalers were at the forefront of a lucrative industry that yielded tons of valuable oil to lubricate the industrial revolution.

The Baleen, known as whale bone, was also used to form the supports of corsets and petticoats.

Over exploitation of bowhead whales around Svalbard saw whaling fleets move to the Davis Strait then up into Baffin Bay.

Dundee’s presence in the whaling industry began in 1753 starting with the ship ‘Dundee’.

But by the mid-19th century whaling was in decline with only Scottish ports –particularly Dundee – persisting until the start of the First World War.

While several hundred ships were lost in the treacherous waters, Nova Zembla, itself is significant because the wreck, which was rediscovered in 2018, is the first identified British Arctic whaling wreck in the High Arctic in Canada.