Scottish ‘witches’ occupy a haunting corner of the nation’s historical narrative, a chapter filled with tales of persecution, fear, and superstition.

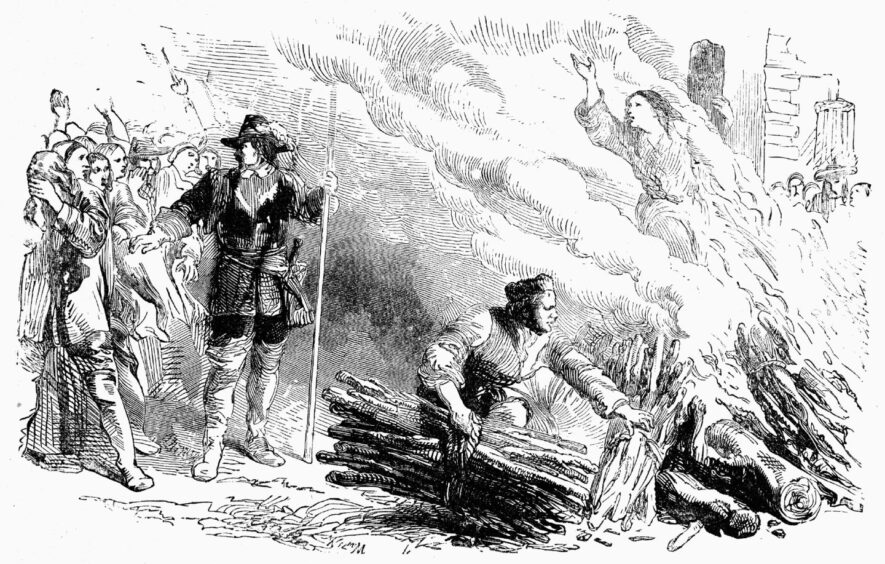

Between the 16th and 18th centuries, Scotland, like many other parts of Europe, witnessed a fervent witch-hunt that led to the accusation, trial, and often brutal execution of individuals, primarily women, accused of practicing witchcraft.

This dark period in Scotland’s past is a testament to the power of fear, the influence of religious dogma, and the scapegoating of those deemed different or threatening.

How many Scots were accused of witchcraft during the witch hunts?

According to the Survey of Scottish Witchcraft – published by Edinburgh University in 2019 – more than 3,800 women and men were accused in Scotland under the Scottish Witchcraft Act between 1563 and 1736, with two-thirds of those accused thought to have been executed.

Infamous cases included ‘The Great Witch of Balwearie’ Margaret Aitken who was arrested in Fife in April 1597 and Janet Cornfoot who, in 1705, was captured by a lynch mob and dragged by her heels to the seafront in Pittenweem.

There she was swung from a rope tied between a ship and the shore, stoned, beaten severely, and finally crushed to death under a door piled high with rocks.

She was then refused a Christian burial with her body thrown into a communal grave.

In recent years, there have been efforts to formally acknowledge and pardon the innocents who were accused and persecuted during this tragic and dark chapter in Scottish history.

But why is it important to remember those who suffered all these centuries later?

Campaign for pardon, apology and memorial

Dr Zoe Venditozzi is a Fife-based writer and teacher, who leads the Witches of Scotland campaign with Claire Mitchell KC.

The pair, who received honorary degrees from Dundee University for their efforts last November, also co-host the Witches of Scotland podcast.

Remembering Scottish ‘witches’ is important as a means of acknowledging historical injustices, promoting tolerance, and preventing the recurrence of such tragedies.

“There’s a saying that those who don’t learn from the past are doomed to repeat it and never has that been clearer than now,” said Zoe.

“This idea of understanding the past to live better lives is what drives the Witches of Scotland campaign.

“Since we started the campaign, we’ve been overwhelmed by the interest shown by people worldwide.

“We’ve rarely had criticism, but when we have it’s usually keyboard warriors having a knee jerk response to a click-bait headline.

“They’ll argue “how far do we go back? 1066? The Roman Invasion?”

“This tedious and superficial angle makes me sorry for the people that have to live day-to-day with these men – it’s always men – as it shows a stunning lack of self-reflection or reading comprehension.

“This is about recognising a gross human rights abuse perpetrated by the state and the church.”

How did the Witchcraft Act work?

The Witchcraft Act was brought into law in 1563 in Scotland and stayed in place until 1736.

Almost 4,000 were accused and around 2,500 executed.

Of these, 84% were women.

Zoe said the accused were questioned and examined.

Initially people were physically tortured.

But when it was decreed that this must cease, they switched to keeping the accused awake for days, even weeks, until they “confessed”.

They were then executed, and their bodies burnt.

This public spectacle both entertained and educated through terror.

The “witch” was denied a Christian burial, and with no body, they could not return from the dead, reanimated by the devil.

In the case of Torryburn witch Lilias Adie in Fife, her grave stone sits on the shoreline between high and low tide.

But what’s the modern-day relevance?

In a population of around a million, there were few communities untouched.

Afterwards, communities deliberately “forgot” and the shame on both sides was strong.

Even when executions stopped, some communities still had the fear of witches.

Experts argue that the trauma of that time echoes in modern Scotland.

That’s why Zoe believes we need to remember the victims today.

“Sadly, during difficult times, humans seek security by attacking the vulnerable,” she said.

“For example, during Covid-19 accusations increased worldwide.

“People sought to explain illness and deaths and pointed the finger at vulnerable people who were ostracised at best and assaulted or killed at worst.

“Witch accusations are occurring in Africa, India, South America, and various other places including some cases in the UK, and the situation has prompted the UN to issue a statement about the dangers of such cases.

“Malawi has been considering putting witchcraft back on the law books, so troubled are they by the situation.

“A vital part of understanding the past is that we memorialise those who lost their lives.

“Just as we are all used to seeing war memorials to remind us that world war must never happen again; we want to see the same done with the victims of the witch trials.

“These ordinary people died in disgrace and shame for a crime that isn’t real.

“They were people just like you or me and we need to remember and pardon them to ensure we work together as a stronger, fairer country.”

What difference can apologies from church and state make?

Last year, Scotland’s then First Minister Nicola Sturgeon offered a formal apology to people accused of witchcraft between the 16th and 18th centuries.

She described it as an “egregious historic injustice”.

Two months later, the Church of Scotland apologised for its role in capturing and torturing ‘witches’.

Lenny Low, the Fife-based author of The Weem Witch, says that while such moves cannot change the past, they are significant steps towards acknowledging the wrongful persecution of innocent individuals.

“A visitor to Fife in the 1650s mentioned in his diary ‘seeing over 40 burnings in a month’,” said Leonard.

“Another claims to have seen 120 witches burn in the same period.

“It became so common that in some church registers it mentions casually ‘some witches burnt today!’

“It was law that a convicted witch’s house and belongings would be split by the church and civil authorities.

“It made great sense to add a few rich witches into the hunts as the Pittenweem ministry tried to in 1704.”

Lenny said the 1736 repeal of the Witchcraft Act brought “howls of anger from ministers”.

He said that over the next 100 years, many wrote bitterly of “not doing the Lord’s bidding as his Bible states – ‘Thou shalt not suffer a witch to live’.

But despite the abolition of the Witchcraft Act, there were still sporadic cases of ‘witches’ being persecuted.

In 1750, a woman had her feet roasted over a fire until the bones fell off in Skye.

An Inverness court in 1883 found a woman guilty of using pins in a doll to affect a love rival.

Lenny’s personal connection

Lenny feels a personal connection because two of his ancestors met the flames – one in 1597 and another in 1644.

Earlier this year he hit out at “snowflake” Fife councillors who ordered the removal of a ‘gaudy’ Pittenweem witch mural.

He’s welcomed the naming of a St Monans street after 17-year-old ‘witch’ Maggie Morgan.

“Its utterly frightening that it took 173 years until the Witchcraft Act was annulled,” he said.

“That all the inhuman acts were committed in God’s name.

“Today, the past has caught up with them.

“The thousands in Scotland that met death on the stakes of fire: for no other reason, the shame is why it’s important to remember those who suffered during the ‘witch’ trials.”

Conversation