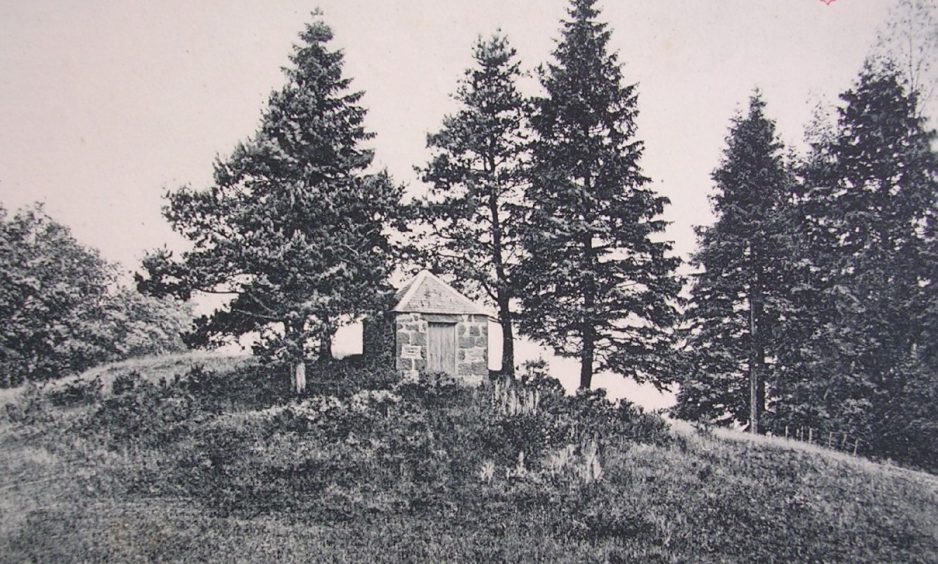

It’s a small, unassuming stone building with a pyramid-shaped roof.

It sits on a grassy hillock next to a lone Scots pine on the outskirts of Comrie.

It could easily be mistaken for a cute wee cottage, or some kind of picnic shelter.

But the tiny building has a hugely important role – it’s the world’s first purpose-built observatory for earthquakes.

Built 150 years ago, in 1874, it’s been measuring seismic activity across the globe ever since.

So why build a dedicated ‘earthquake house’ in Comrie? Quite simply, it’s the earthquake capital of the UK!

The Shaky Toun

The Perthshire village recorded thousands of mini quakes and tremors between the late 1700s and the mid 1800s, and was nicknamed the “Shaky Toun” as a result.

It lies close to the Highland Boundary Fault which runs between Stonehaven and Dumbarton, and it’s thought that a “sub” fault lines comes off near Comrie.

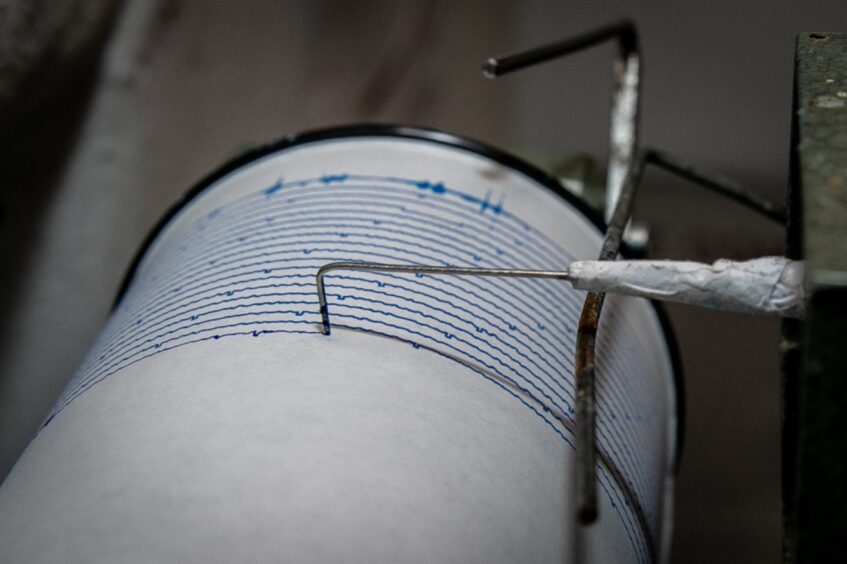

Every nine days, Chris Palmer, who has the coveted and unusual role of ‘earthquake house custodian’, must change the roll of paper on a machine known as the Lenartz chart recorder.

It’s up to Chris, 73, to keep an eye on and maintain the curious building.

While the earthquake house is usually closed to the public – it’s full of fragile equipment that could easily be damaged – I’m lucky enough to get inside it with Chris.

It’s a short but steep stroll up to the recording station on a small hill known as The Ross, but it’s well worth it for the views.

Earthquake house custodian

Chris, who’s been custodian for 20 years, explains that the house boasts both modern and traditional earthquake measuring devices, and warns me not to trample on the delicate replica of one of the early seismic Mallet seismoscopes.

The original comprised of two planks of wood running north to south and east to west with cylinders of differing sizes placed on top.

These would fall on to sand during a tremor, allowing Chris’s predecessors to work out the scale and direction of any seismic activity.

A modern seismograph now operates inside the building, and as well as keeping track of local tremors, the equipment records devastating quakes across the globe.

Records of quakes

Sheets of paper that note details of these various disasters are plastered all over the walls.

The first recording of a local tremor was made by James Melville who wrote in his diary that an earthquake was felt across Perthshire in July 1597.

The Reverends Ralph Taylor and George Gilfillan documented a number of strange noises, movements and tremors in Comrie at the end of the 18th Century, with a major series of 70 shocks in 1788.

And on November 10 1790, Reverend Taylor noted: “It was market day at Comrie and the people… felt as if the mountains were to tumble on their heads.

“The hardware exposed for sale in the shops and booths shook and clattered, and the horses crowded together with signs of unusual terror.”

“No-one really knew what an earthquake was at that time,” says Chris.

“I’ve experienced a few in the 20 years I’ve lived here. It’s normally a loud bang, like a bomb going off or a quarry blasting, and the ground shakes.”

The Great Quake

The so-called “Great Quake”, recorded on October 23 1839, was a major incident. It struck at 10pm with 20 aftershocks recorded over the next 24 hours.

Many houses in Comrie were damaged, with chimney pots collapsing, walls cracking, and windows smashed, and it even breached the Earl’s Burn dam in the Gargunnock hills near Stirling.

Twelve miles to the north, at Amulree, fissures opened in the ground, one of which was 200 yards long.

It was this major event that inspired two men from the village, shoemaker James Drummond and postmaster Peter Macfarlane, known as the ‘Comrie Pioneers’, to draw up plans for the Earthquake House.

The Comrie Pioneers

They first created a basic instrument consisting of two wooden planks in 1840 to detect quakes – an early version of the seismograph.

The pair began keeping formal records of seismic activity, using an intensity scale developed by Macfarlane, and submitted their notes and experiences to the Royal Society of Edinburgh, in a bid to better understand the ongoing phenomenon.

This resulted in a variety of instruments being installed around the village to measure activity, with one in the parish church steeple and another in the Post Office.

In the years that followed, the Committee for the Investigation of Scottish and Irish Earthquakes was established.

By 1874, the study of earthquakes had advanced significantly and so the world’s first purpose-built earthquake observation centre was constructed on top of the local bedrock in Comrie.

Fell into disrepair

The building became redundant in 1911 as more advanced technology was created around the country.

It quickly fell into disrepair, and people forgot about the earthquake house.

However, in 1977, it was designated as a building of special historical interest, and in the 1980s, a team from the British Geological Survey helped Perth and Kinross Council after they decided to revive it and install modern equipment.

This included the Lenartz chart recorder, which records nine days’ worth of information on a paper chart.

Renovated and restored, windows were added to allow curious visitors to look in and see both the old and new seismometers in action.

Smallest listed building

It’s believed to be the smallest listed building in Europe.

However, while seismic stations across Britain are linked to the British Geological Survey, the Earthquake House is no longer.

“There’s a remote sensing station up in Glen Lednock, just north of Comrie, and that sends information now,” says Chris.

“We used to send papers for them to look at, but they said we didn’t need to do that anymore.

“They did think about linking this up, but it all seemed a bit complicated. It still works, and if anything goes wrong, the British Geological Survey will maintain it for us.

“And they do still regard it as a really significant building in its historical context.”

(Don’t) jump around!

The equipment inside is so sensitive that if we jump around too much, we could cause our own little quake, warns Chris!

So I try to move round the building without being too clumsy.

As well as keeping track of local tremors, the equipment records devastating quakes across the globe.

Last year, it recorded tremors from the deadly Turkey-Syria earthquake.

Deadly quakes

On February 6 2023, a 7.8-magnitude earthquake and various aftershocks struck southern and central Turkey, and northern and western Syria. At least 56,000 people were killed in the disaster.

It also picked up the August 2016 earthquake in the Italian village of Amatrice, and the Tohoku earthquake in Japan in 2011, which destroyed part of a nuclear reactor.

The Indian Ocean earthquake which led to the Boxing Day Tsunami in 2004 was also recorded in Comrie.

“The tsunami went round the paper twice,” Chris recalls.

“There’s been a lot of activity up the west coast recently, including in Mull, Morven and Knoydart.”

Tourist attraction

Chris believes the curious little house is still of great interest to visitors and tourists alike and I absolutely agree.

If ever there’s a significant tremor recorded, he writes all the information on a sheet of A4 and pins it in a window.

The single, gnarled, pine tree that stands next to the house is also significant.

It was planted the same year as the earthquake house was built – in 1874.

“There were originally four planted to keep the effects of wind off the building,” explains Chris. “The other three blew down.”

While 2024 marks the 150th anniversary of the earthquake house, Chris isn’t sure if there are plans to celebrate.

I suggest a party on the hillock, maybe in summer, and he seems quite keen on the idea, so we shall see.

Meantime, it’s well worth a visit, even though it’s closed to visitors – unless Chris happens to be there changing the paper.

Still, there’s loads of information stuck up in the windows and you can learn quite a lot from simply peering in.

Conversation