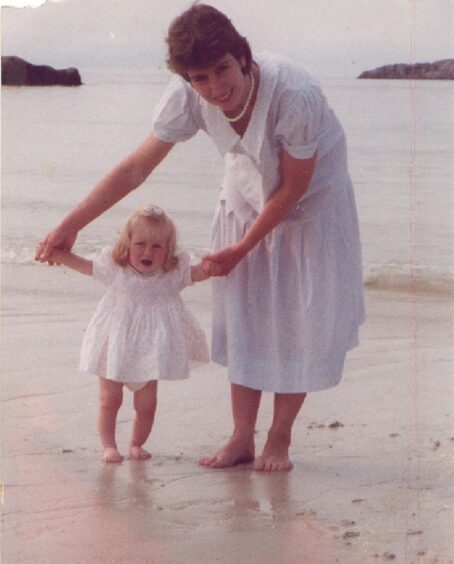

When Gill Fyffe was initially told she needed a blood transfusion to help her body recuperate after the birth of her daughter at Ninewells Hospital, she refused.

It was 1988 and, unsettled by the ongoing AIDS crisis, she told doctors at the Dundee-based hospital that she would rather just go home and rest.

But the doctors insisted and through the blood transfusion she contracted Hepatitis C, a condition that would go on to “destroy” the now 65-year-old’s health.

“My husband and I held out for 36 hours saying we didn’t want it,” she remembers.

“But then the doctor said: ‘Well you might not make it through the night.”

Gill and her husband Stan reluctantly agreed to the procedure, but in the end she didn’t receive the blood till the next day.

“It was clear I wasn’t in any danger.

“My husband was really cross. He pointed out that this wasn’t what we had agreed to at all.

“But by that point I was just so exhausted that I said let’s just get started now.”

Infected blood scandal

Gill is one of the estimated 3000 people in Scotland, and thousands more in the UK, who were given contaminated NHS blood and blood products in the 1970s and 1980s.

While Gill developed Hepatitis C, a condition that can cause potentially fatal damage to the liver, others contracted HIV and some both diseases.

The UK was reliant on supplies imported from the US, where they collected blood from prisoners, drug addicts and other high-risk groups.

Gill is telling her story just days before the release of a long-awaited report from the Infected Blood Inquiry.

The inquiry, launched in 2017 and chaired by former High Court judge Sir Brian Langstaff, is due to publish its findings early next week.

When did Gill learn she had hepatitis C?

Gill, who was 29 years old at the time, had been working as a teacher in St Andrews before she had her daughter.

She tried to go back to work after Lucy was born, but in the end had to give up her job because she was always too tired. At first, she couldn’t understand why.

“Over the next seven years I became so exhausted, I was unnaturally exhausted,” she explains.

“On one occasion I was so tired I fell asleep at the wheel in the middle of the afternoon.

“I drove off the road with my children strapped in the back of the car and wrote the car off.

“It was really awful. I just kept thinking what is the matter with me?”

When Gill’s daughter was seven years old, she received a letter from the Blood Transfusion Service.

“[The letter] was saying I should get a test because the transfusion I had was probably infected.

“I just went into a panic because I thought it has been seven years, I am bound to have infected the children.

“I was absolutely terrified for my children.”

Doctor confirmed Gill was infected

After receiving the letter Gill and Stan, 67, who were still in shock, raced to their local GP surgery.

“The GP already knew about this and said he had been waiting for me to call,” Gill says.

“I told him I wanted my children tested. He went on to test me, my husband and my children.

“We went back to the surgery the next day to get the results and when the doctor said the children were clear I was so relieved.

“He then turned to my husband and said you are clear too.

“And when he did that, I just knew I was infected, otherwise he would have told us all together we were clear.”

The doctor told Gill she had Hepatitis C – she had contracted it from the infected blood.

She went to Edinburgh Royal Infirmary to have treatment using a drug called Alpha Interferon.

But the treatment wasn’t successful.

So in 2000, she volunteered to be a ‘guinea pig’ for a trial of a new unlicensed treatment called Ribavirin, which she took alongside Interferon.

It worked, or so she thought.

Gill went back to work as a teacher

Gill felt well enough to go back to teaching after a year. She took a teaching post at Fettes College in Edinburgh where she stayed for six years.

But over that time she found she was becoming unusually sensitive to light. She struggled to be in a classroom where sun was shining through the window.

Her face would swell up and blister.

And she couldn’t use a computer either because of the glare from the screen.

“A specialist told me to avoid daylight and because I couldn’t use a computer, I couldn’t do the job so I had to resign.

“Even now in the summer I am still really restricted – I can’t sit in the garden. And in the winter I can go out but I have to wear a hat.”

Hospital tests later confirmed her sensitivity to light was one of the side effects of Interferon, the drug she initially used to treat Hepatitis C.

Connecting with other infected blood victims

Her husband, who was self-employed as a structural engineer, became the main breadwinner for the family.

Gill spent her time writing her memoir, ‘Lifeblood’ about her experiences.

And she was encouraged to tell the full story of the infected blood scandal.

“My children would take turns in typing up what I had managed to write,” she explains.

“When my book was first shown to the publisher he said ‘well that’s your story but you have got to include the national story’, which was starting to become known.

“Until that point we had no idea what a big disaster it had been.

“Or in fact that people had known the blood supply was contaminated.

“Through research we discovered the true extent of it and that thousands of people had died. It was such a shock.”

All the information that Gill gathered while researching for her book, which was published in 2015, has been used as evidence in the new infected blood inquiry.

Gill’s hopes for the inquiry report findings

The current inquiry is the second one that has been held to look into the infected blood scandal.

The first was the Penrose inquiry. It made only one recommendation – that anyone in Scotland who had a blood transfusion before 1991 should be tested for Hepatitis C, if they had not done so already.

Today Gill, who is living in Blairgowrie, Perthshire, believes the new inquiry, chaired by Sir Brian Langstaff, has been a ‘game-changer’.

“All of a sudden what happened was acknowledged.

“So I think the new inquiry has been absolutely marvellous.”

‘People need to be compensated’

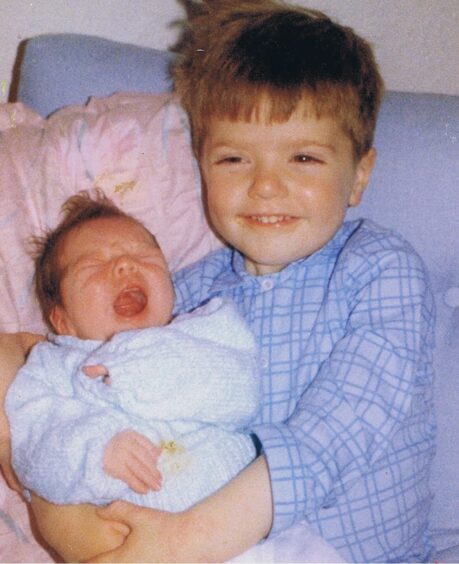

Gill said her family, including her two children, Rory, 38, and Lucy, 35, have been incredibly supportive.

“My children both gave evidence at a hearing for the inquiry which was heart-breaking for my husband and I.

“As we get older, our children feel more responsible for us.

“So if we were able to have financial security again that would be a relief for them.”

Gill plans to travel to Westminster on Monday to hear the report findings from the infected blood inquiry with her husband Stan.

“People should be compensated as a result of this.

“Some have lost children and it has split families apart.

“It has also taken away the lives we would have had. I haven’t had the career I would have had which would have given my family financial security.

“So I think to be compensated for something like that – even at this late stage – would allow life to restart.

Conversation