Michael Alexander reflects on the 75th anniversary of the Normandy Landings which involved thousands of Black Watch troops with links to Tayside and Fife, and speaks to another veteran who was there.

It was the largest seaborne invasion in history – the operation that began the liberation of German-occupied Europe from Nazi control and laid the foundations of the Allied victory on the Western Front.

On June 6, 1944, more than 300,000 Allied troops – including dozens of Scots regiments – fought their way onto the beaches in France.

Codenamed Operation Neptune, D-Day marked the beginning of the end of the war in Europe and, supported by aircraft and French resistance fighters, the Allied forces were able to link up and establish a firm foothold in France.

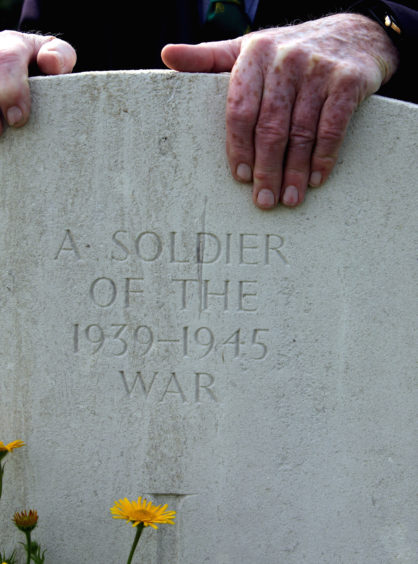

With the 75th anniversary of this most ambitious and dangerous wartime operation upon us, a dwindling number of Courier Country veterans remain to give first-hand accounts of what it was like to be involved. However, their stories of bravery and sacrifice live on.

Major Ronnie Proctor, 74, secretary of the Black Watch Association and honorary curator of the Black Watch Museum in Perth, was 15-years-old when he signed up in 1960 at the start of what became a 40-year career with the Black Watch – the regiment which traditionally recruited from Tayside and Fife.

As a junior soldier, he recalls the majority of the sergeants and officers wore Second World War medals and, while growing up, the war was, of course, very fresh in peoples’ minds.

Major Proctor has met “countless” veterans over the years, including many who fought at Normandy or its immediate aftermath. However, with the majority no longer here to tell their stories, he often recounts their tales instead.

“Normandy was really a very salient part of the Second World War as it was the invasion of Europe,” said Major Proctor, who is currently also Angus Provost and who will be celebrating the 100th anniversary of the Black Watch Association on June 15.

“The 5th Battalion Black Watch – the Angus battalion – were there at the beginning. They landed on D-Day but later on. They weren’t in with the first wave. It was closer to the evening. They were 800 to 1000 guys.

“They were then followed by the two other battalions of the Black Watch – the 1st Battalion and the 7th Battalion – originally the Fife battalion – which were part of the famous 51st Highland Division. It has to be remembered, however, that by this stage in the war the Black Watch would have had members from across the UK.”

The Black Watch Museum doesn’t hold Second World War personnel records – after the First World War these were held at the Army Personnel Centre in Glasgow.

However, it does hold the war diaries written by the adjutant of each battalion, giving an account of the fighting on each particular day.

With Black Watch battalions having fought in North Africa and Sicily before being pulled back for Operation Overlord – the codename for the Battle of Normandy – Major Proctor imagined what it must have felt like when the soldiers, who spent months training in England, boarded their LCIs (Landing Craft Infantry) at Tilbury Docks and moved out into the lower waters of the Thames estuary on June 3 – not quite knowing what to expect or when, yet aware there was at least a “50:50 chance of being killed”.

Quoting from ‘The Spirit of Angus’ – a book by the late Perthshire-born and raised Black Watch commander John McGregor about the history of the 5th Battalion Black Watch – Major Proctor said: “When daylight crept in from the east, those on deck saw the incredible sight of ships of every size and purpose from vast battleships to destroyers…to LCIs to cargo ships, all steaming in the same direction, many towing cumbersome barrage balloons.

“Overhead there was the occasional glimpse of waves of aircraft thundering towards their targets. It was a sight never to be forgotten and set the adrenalin flowing in the beholders…”

While the men of the 153rd Infantry Brigade of the 5th Battalion Black Watch did not experience heavy fighting on the beaches given that an initial wave of commandos had already waded ashore and stormed the German strongholds, they soon became embroiled in one of the bloodiest battles of 1944, in what became known as the Triangle of Death.

In his 1950 book The Black Watch and the King’s Enemies, Bernard Fergusson said: “Turning east from the beaches, they marched along parallel to the coast and soon came to the woods surrounding Douvres where a force of fanatical Germans was still holding out in defence of the radar station, which it was their duty to guard.”

The late Dr Tom Renouf, whose story is told within the Black Watch Museum, was a young soldier who survived the heavy fighting to the west of Caen and was transferred to the 5th Battalion – only to be wounded.

Ambushed by the heavy Spandau machine-guns and 88mm mortar fire of the SS, he later said of the fighting: “The SS forces and Panzers turned the area around Caen – a vital communications junction just 10 miles from Sword Beach – into a seething cauldron of death and destruction.”

Forced to retreat, their commanding officer Lieutenant Colonel Thomson was ordered to support the paratroopers of the 6th Airborne Division and helped to defend Pegasus Bridge.

By early August 1944, the 5th Battalion were sweeping through France, Belgium, The Netherlands and across the Rhine to Berlin with the rest of the Allied forces.

However, the campaign left most of this part of Normandy in ruins and more than 120,000 civilians and soldiers from various regiments died.

Another man thinking of fallen comrades this week will be D-Day war veteran Eric Tandy, who celebrated his 95th birthday in Glenrothes on February 26, and who is due to be officially presented with France’s highest military honour – the Legion D’Honneur – on the 75th anniversary of D-Day.

As told by The Courier in February, the then 20-year-old paratrooper, who served with the 7th Battalion The Parachute Regiment, was accidentally dropped behind enemy lines on D-Day and tried to make his way back to his own regiment through a minefield only to be captured by the enemy and held half-starved in a prisoner of war camp before being force marched with fellow POWs to become human shields in Berlin.

He was the sergeant in charge of an aircraft carrying paratroopers from England to France as airborne forces of the British Army took part in the infamous Pegasus Bridge campaign during the early stages of the Normandy Landings.

Midway through the job of deploying the soldiers out of the aircraft, a medic was wounded by anti-aircraft fire, which resulted in him overshooting the drop zone by about 10 miles.

On landing, a gunner corporal and he attempted to make their way back to Pegasus Bridge where the Allies’ mission was to seize the bridge over the Orne River and prevent German armour from crossing over to attack the eastern flank of the landings at Sword Beach.

However, they came across two Commandos trapped in a minefield – one being mortally wounded and the other unhurt.

Eric used his experience of minefields to get them out of the danger zone.

However, later that morning, and after coming under enemy fire, they were taken prisoner after German troops set up camp to cook breakfast and found them hiding in a hedge.

After a couple of days, Eric and his colleagues were taken to Stalag 357 at Fallingbostel where he was a Prisoner of War for approximately eight months.

Towards the end of the war, the Germans were moving all Prisoners of War towards Berlin in an effort to stop the Allies – the Russians – from bombing Berlin and they were amongst them. The Germans eventually abandoned them en-route when they were liberated by British Airborne Troops.

Telling The Courier how the delivery of his medal was “totally unexpected” when a small parcel arrived at his house in early May, Eric said: “On opening it, I couldn’t believe my eyes.

“There was the Legion d’Honneur, beautifully displayed in its red box – an impressive sight. The accompanying letter explained what it was for and the wording was so very moving.

“I still didn’t understand how I had been awarded the medal, until my son-in-law Grant explained that my daughter, Lorraine, had recently read an article about a fellow Paratrooper who had been awarded the Legion d’Honneur and that the French Government had decided, back in 2014, to award all living D-Day Allied landing veterans with this medal.

“They did not tell me that they were applying for the medal or that they were hoping it would come before the 75th anniversary of Pegasus Bridge – a life-changing experience for me at the time.

“That the French Government could give me this award is extremely gratifying.

“I am both touched and deeply honoured and would like to express my heartfelt thanks to them.”

Brigadier (Retd) Robin Bacon was commissioned into the Royal Corps of Transport in 1978, which became the Royal Logistics Corps in 1993.

He left the Army as a Brigadier in 2010, and has been the Chief Operating Officer of ABF The Soldiers’ Charity since March 2010.

The charity was formed on D-Day in 1944 to ensure that soldiers returning from the Second World War and campaigns such as D-Day were taken care of in ways that hadn’t been evident after the First World War.

Describing D-Day as a “fantastic show of military strength and planning” after years of the Allies being on the defensive, he drew comparisons – albeit on a different scale – with his own experiences of being part of the logistic planning team that prepared for the retaking of Kuwait from the Iraqis during the first Gulf War in 1991.

“People always say ‘you don’t have enough manpower or equipment to do this or that’”, he said. “But in the Gulf we were able to demonstrate if you have the will you are able to do it, and we had the will of the Prime Minister and good planners.

“It was done on a bit of a wing and a prayer in that we had to take equipment left right and centre from other units to make up the units to be able to go off and fight on what we called Operation Granby.

“I imagine it was very similar on D-Day because they had lost an awful lot of kit. It was just the culmination of a massive amount of effort and planning. To think they didn’t have modern day communications. It was a stunning piece of work to be able to get on and do it. What enormous pride in seeing that happen!”