A theme of Nicola Sturgeon’s speech at the SNP’s conference in Aberdeen was challenging the assumption that sticking with the Union represents safety for Scotland, while choosing independence is the risky option.

Placing her argument firmly in the context of the damage caused by Brexit and the shocks to the system created by Liz Truss’s government, the First Minister put it this way:

“Back in 2014, the Westminster establishment told us it was the UK’s standing in the world; its economic strength; and its stability that made independence impossible. Now they say it’s the UK’s isolation, its weakness and instability – the very conditions they created – that means change can’t happen.”

She was right to observe that the economy is what gives people “most pause for thought” about independence.

A lot, therefore, is riding on the document to be published by the Scottish Government next week, setting out the economic case for Scotland to be independent.

Partly it will focus on how we can build economic strength on the nation’s vast renewable energy resources.

However, she was equally correct to point out how it is now clear for all to see that “the UK does not offer economic strength or financial security.”

It was of no comfort to have Britain’s parlous predicament further evidenced the morning after Ms Sturgeon’s speech, with the announcement by the Bank of England of yet another intervention in the markets to buy more government bonds because of a “material risk” to the UK’s financial stability.

What we are living through just now obviously has its own distinct characteristics.

But it is well worth noting that British economic weakness has a long and depressing history.

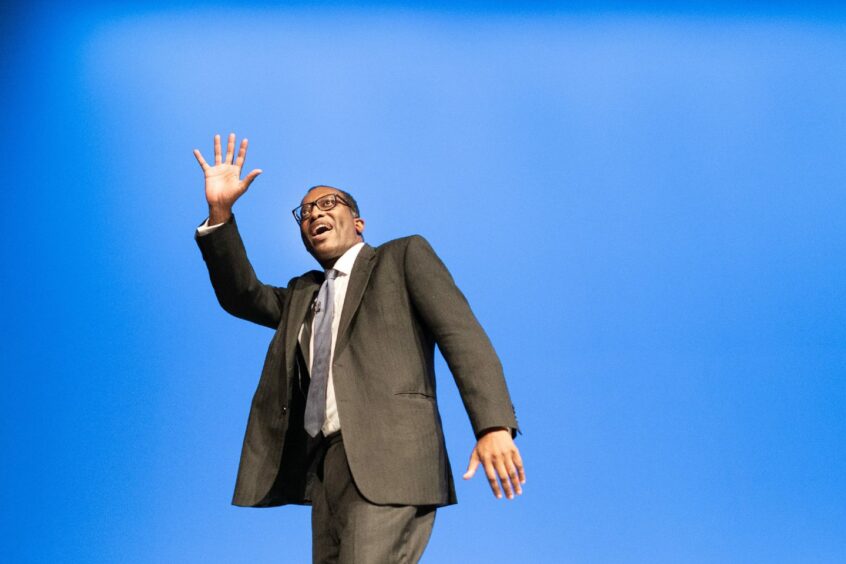

How will Kwarteng handle calls for cuts?

Last week, as a “thank you” for taking part in an event where business met academia, I was given a book that I fear reflects my reputation as a political anorak.

The Labour Government 1964-1970: A Personal Record is a mighty tome of some 800 pages by the prime minister of those times, Harold Wilson.

Describing the sterling crisis into which his new government was immediately plunged, Mr Wilson lamented what the Bank of England Governor was urging him to do to win confidence and avert “a disastrous haemorrhage” of the pound.

He wrote: “we had to listen night after night to demands that there should be immediate cuts in Government expenditure, and particularly in those parts of Government expenditure which related to the social services.”

This week, we are informed by the Institute for Fiscal Studies that the Chancellor, Kwasi Kwarteng, has to make cuts of more than £60 billion just to stabilise debt as a share of national income in 2026/27.

That’s if he sticks with the unfunded tax-cutting plan that caused many of the problems in the first place, including higher borrowing costs.

Mr Wilson was to be sympathised with in the sense that his strong desire was to boost public services rather than cut spending.

He had also inherited problems such as a chronic balance of payments deficit from the previous Tory administration.

Support for Scottish independence is linked to state of British economy

As the era of austerity reminded us, Conservatives tend to have few qualms when it comes to imposing cuts.

🏴 Next week, @scotgov will publish the economic case for independence, setting out how we can unlock Scotland's massive potential free from Westminster control.

📣 @NicolaSturgeon: "An economy that works for everyone. That is the prize of independence." pic.twitter.com/J9NTrYTPh0

— Yes (@YesScot) October 11, 2022

And to a large extent Mr Kwarteng can be regarded as the architect of his own, and the country’s, current misfortunes.

Concern about Britain’s economic decline in the late 1960s was undoubtedly one of the factors that contributed to the rise of the modern SNP, notably Winnie Ewing’s famous Hamilton by-election triumph in 1967.

A question to be answered today is if the UK’s current travails move more people towards believing that independence offers a better future.

Conversation