When The Courier reported in January that minerals specialist Erris Resources hopes gold worth £300 million could be extracted from hills in Perthshire, it raised the possibility of a mini gold-rush and cries of ‘there’s gold in them thar hills’!

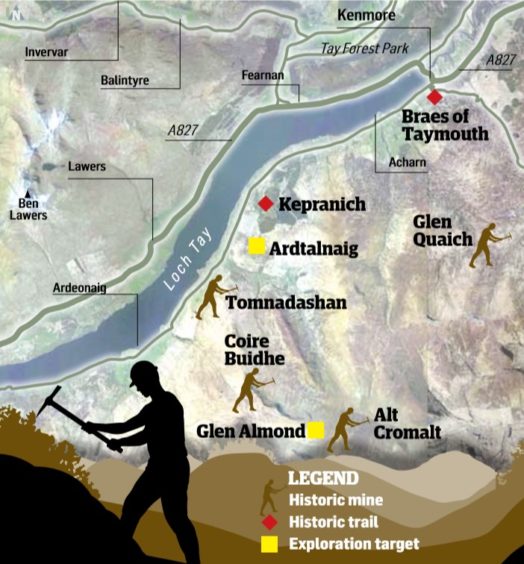

The company believes there is “excellent potential” in prospecting for gold in sites to the south of Loch Tay, and it plans to start prospecting and mapping shortly with the ultimate aim of finding 250,000 ounces of gold.

But for Fife Council archaeologist Douglas Speirs, the “entirely possible” realism of a major gold find in Perthshire has rekindled his fascination with a period in history which saw more than 2000 speculative gold miners descend on the Lomond Hills in Fife during a single month in the 19th century.

“To put events in context, you have to appreciate the worldwide news sensation that was the Californian gold rush of 1848/49,” explained Mr Speirs.

“Scottish newspapers were awash with reports from 1848 onwards with reports of the phenomenal gold finds and the wealth being made.

“Then in September 1851, gold was found in Australia and again, the papers were stuffed full of sensational stories of the phenomenal wealth to be made by all.

“In 1852, any paper you read in Scotland, in almost every issue, would have a story of ordinary folk getting rich beyond belief in prospecting in California or Australia. The papers were full of adverts encouraging people to up sticks to California or Australia, and get rich quick panning for gold under beautiful blue skies.

“Labouring classes in Scotland had zero chance of bettering their station in life so it’s not surprising that many were tempted to become miners.

“It’s against this background that news of the Kinnesswood gold rush was announced to the penniless labouring classes of Scotland in May, 1852.”

Mr Speirs explained that sometime around or before the first week of May 1852, an un-named convict transported to Australia, but originally from Kinnesswood, near Loch Leven, had written home to Kinnesswood and said that he recalled seeing sparkling gold-like minerals in rocks on the Bishop Hill above Kinnesswood, very similar to the rich gold-bearing rocks then being mined to great profit in Australia.

In the first week of May 1852, his village friends started prospecting on the Bishop Hill.

News spread like wild fire and by the second week, hundreds of local miners started to resort to the diggings after shifts and in their spare time.

By the third week, reports told of as many as 2,000 people seen up the Bishop Hill all digging in and around the Clatteringwell Quarry. This was a long-established limestone quarry that had been worked since at least the 17th century.

Newspapers told of miners and people of all sorts – although mainly labouring classes like hand-loom weavers – coming from as far as Dundee, St Andrews, Stirling and Haddington and everywhere in between.

“The usually quiet and industrious inhabitants of Fifeshire have been, within this last few days, thrown into a state of the greatest excitement by the report that gold had been discovered on the Lomond Hills, and other places near Falkland,” reported the Glasgow Herald on May 24, 1852.

“Considerable numbers were attracted to the spot last week, and there were upwards of 2500, both old and young, actively engaged at the diggings including a number of colliers from Alva near Stirling.”

But the Kinnesswood ‘gold-rush’ was to be short-lived. On May 24 1852, samples of the yellow glistening ore and the golden spherical concretions, known as ‘fairy ball’s or ‘fools gold’ by contemporary limestone quarriers, had been assayed and the results published in newspapers. The ‘gold’ was common iron pyrites. By the end of the month, the gold rush was over.

Mr Speirs said the actual traces of the 1852 diggings are still visible on the ground but are best understood when seen from the air.

As CEO of Edinburgh Assay, Assay Master Scott Walter is responsible for overseeing one of four Assay offices in the UK authorised to test precious metals so that manufacturers can comply with the Hallmarking Act through an Act of Parliament.

An Assay Master has been employed in Edinburgh since 1682 and Mr Walter’s role is to ensure national and international gold standards are met.

He has been closely involved with the Cononish gold mine run by Scotgold Resources Ltd at Tyndrum.

But while the geology of the area south of Loch Tay might well throw up further gold finds, the key message from him is that for anyone buying or panning for Scottish gold it’s all about provenance.

Referring to the revelation In December that an anonymous treasure hunter claimed to have discovered the UK’s largest gold nugget in an unnamed Scottish river, he said: “It hasn’t bottomed out for provenance yet. There are people looking to see if it’s actually from that place.

“I’m not suggesting for a moment anyone would do such a thing, but if you imagine the premium that would gain if you take gold from somewhere else and melt it down and make it look like a nugget pretty easily, throw it into the river and say ‘wow look what I just found’. All of a sudden that’s a very expensive piece of gold. So I think provenance is the big challenge that panners face and it’s a big challenge that people who buy from panners face.

“Consumers are trusting that the retailer actually got it from a panner who actually got it in a river in Scotland.

“You need to provide evidence based on chain of custody. That’s been done at Cononish. They have good systems.

“The more certain you can be about providing that provenance the more assured the retailer and trader are.”

According to Mr Speirs, gold of unknown origin had been worked in Scotland since the Chalcolithic period (the ‘Copper Age’) with the earliest datable native gold artefacts dating from around 2,400BC.

The earliest reference to gold digging/panning in Scotland is in a charter of David I dating from the 1140s and relating to Fife. But there is no evidence of gold mining in 12th century Scotland.

In 1424, the Scottish Parliament held at Perth granted to the Crown rights to all the gold mines in Scotland, and all silver mines in which three halfpennies of silver could be refined out of a pound lead.

Around 1511, in the reign of James IV, gold was found in Crawford Muir (Clydesdale, Lanarkshire). Indeed, Crawford Moor quickly became, and remained, the UKs leading gold-field with considerable activity during the 16th century.

James V was particularly interested in gold and silver mining and lost money hand over fist in the search for mineral wealth. Ultimately, his get rich quick scheme failed and gold and silver did not, as he’d planned, rescue the finances of impoverished 16th century Scotland.

But using hired-in Mexican expertise brought straight in from the New World where the insatiable Spanish hunt for gold had been in full swing for decades, Scotland was subjected to a nationwide hunt for minerals that did lead to reasonable quantities of gold and silver being both found and mined.

Indeed, much of the 16th century Scottish crown jewellery as well as the gold coinage of the country – including James V’s prized bonnet pieces – were struck from Scottish gold.

Records suggest gold was found at ‘Sarus Arrius’ on Benarty Hill, on the south-side of Loch Leven in the 16th century.

The same source suggests silver and copper was found at Largo Law in Fife and that gold was found at Longforgan and at Muckart.

After Kinnesswood, there was a similar ‘gold rush’ in Sutherland in 1868/69 – actually producing a reasonable amount of gold.

In Perthshire, Cononish near Tyndrum was historically known for lead mining but gold was not discovered there until the 1980s.

A 10oz nugget from Cononish was the first commercially mined gold to be extracted in Scotland.

Mine owners Scotgold Resources released 10 limited edition 1oz gold rounds in 2016, which sold for an average of £4,557 per oz.

In January, Erris Resources said it believes there is “excellent potential” in prospecting for gold in sites to the south of Loch Tay.