Scots have left their imprint wherever they have travelled in many different areas – from medicine to the arts and science to technology.

But in Europe there are some very specific fields which might have foreign names but have distinctive links to Scotland – and these are the football fields in such places as Malta, Gibraltar and at clubs such as Sevilla in Spain.

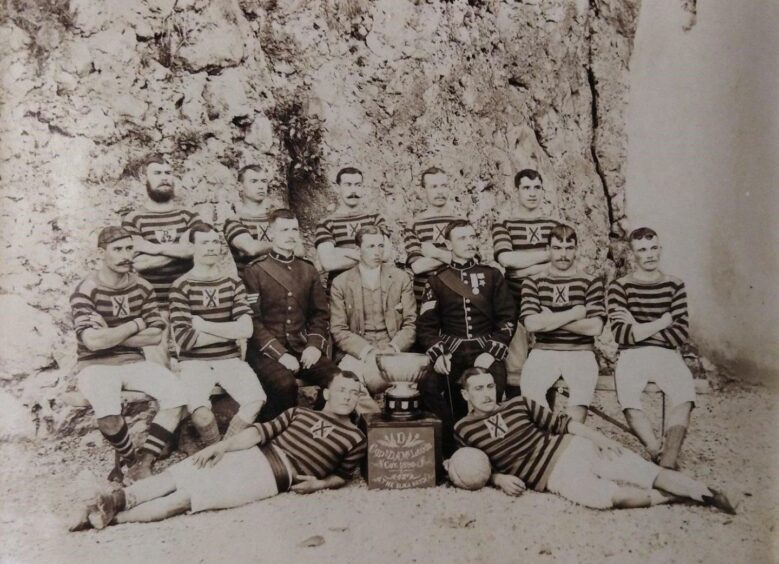

Towards the end of the Victorian era, the soldiers of 42nd Black Watch, a battalion made up of Scots, the majority from Dundee and the north-east, were the pioneers of the sport in different parts of the Iberian peninsula.

Their drive and enthusiasm proved the catalysts for the foundation of Sevilla FC while celebrating Burns Night in January 1890.

The Andalusian capital club, which is close to Gibraltar, subsequently hosted the first-ever club match to be played in Spain, which ended with them recording a 2-0 victory over Huelva Recreation Club.

However, it was a reflection of the significant Caledonian involvement in spreading the football gospel that, just a few days later, a match report of the ground-breaking contest was carried in the pages of The Courier.

Scots inspired Iberian counterparts

These were heady days for the game, after The Black Watch troops arrived from the Himalayas in Malta and Gibraltar in 1889 and 1890.

In the space of just a few months, there were goalposts and corner flags where none had previously existed and the early matches were billed as festivals of entertainment with something for everybody in the community.

Charles J Cumbo, the author of a book about the rise of football on the European rock, said: “There is no doubt that the excellent standard of play of The Black Watch awoke great interest in football amongst the civilians.”

These words were endorsed by the Dundee Evening Telegraph, which covered a fixture between The Black Watch and the Royal Artillery, describing the occasion as being: “Like a fair, with vehicles, stalls and a brilliant variety of dresses worn by the public (which amounted to at least 10,000 people), and which showed the growing popularity of football since the 42nd arrived.”

The rapport between the soldiers and residents was obvious from the outset.

They may not have shared much else in common beyond the football realm, but many of the troops were thrilled at getting involved in inter-regimental contests and cheering on the launch of local teams in Gibraltar.

The Gibraltar Chronicle, the local newspaper, once again highlighted the popularity of the 42nd Black Watch among the civilian population.”

Javier Terenti

And these passionate Scots were very proud of their roots.

The Dundee People’s Journal was among the publications to highlight their activities and, in an article published in November 1891, carried the headline “Dundee Soldiers in Gibraltar”, which featured the contents of a letter written by a Black Watch soldier to a friend back home in Tayside.

He stated: “Perhaps you might like to know what sort of a regiment ours is.

Well, sir, the men nearly all belong to Dundee.”

The arrival of a Leicester stalwart

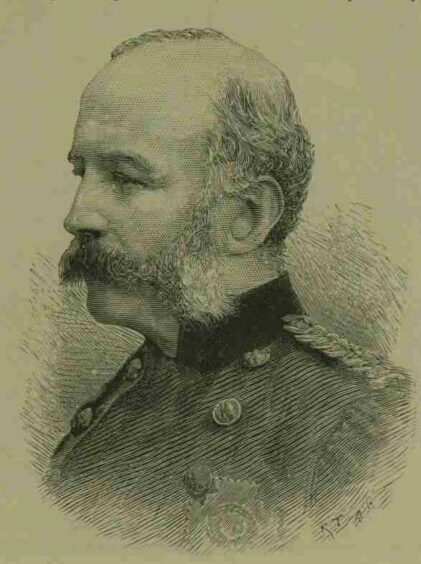

Having been instrumental in the creation of Sevilla FC, the 42nd Black Watch received support from a somewhat unexpected ally: Sir Leicester Smyth, who was appointed the new governor of Gibraltar in mid-August 1890.

Not all these panjandrums liked football – the majority preferred rugby and cricket – but Smith was an enterprising individual and bought into the flourishing culture, even though he only remained in the post for four months before his sudden death while he was on leave in London.

It was a tragic blow to his family, but Smith’s legacy lived on through his donation of a football cup that was subsequently fought out between the different battalions which comprised the garrison in Gibraltar.

And, with silverware up for grabs, here was a new opportunity for The Black Watch to prove themselves against their rivals. One they didn’t squander.

Javier Terenti, a football historian at Sevilla FC, has delved into the chronicles from that period, which paint a vivid picture of these early cup clashes.

The language used in the contemporary newspapers and magazines may occasionally be antiquated, but they evoke the keenness of competition and the commitment from the Scots, who duly continued to be trailblazers when they triumphed in the inaugural Governor’s Cup in 1891.

Their team, which featured players from Dundee, Arbroath, Perth, Greenock, Glasgow and several other communities, held nothing back – and even though this was “only” a military event, they were delighted at their achievement.

Lifting the cup and the glory

Mr Terenti said: “At three o’clock in the afternoon on March 28, the third and (deciding) final match of the first edition of the Governor’s Cup began.

“Such a number of spectators had never been seen before in a football ground in the Rock.

“The dominance belonged to the 42nd Black Watch from start to the end of the match, although they had to wait until the second half to score the two winning goals, both scored by Brennan, the hero of the afternoon, whom the crowd pulled on their shoulders off the field.”

The winning side was listed as Craig (Dundee); Barr (Greenock), Robertson (Inverkeillor); Greliche (Edinburgh), Duncan (Falkirk), Gray (Perth); Brennan (Clackmannan), Valentyne (Arbroath), Smith (Arbroath), Kelt (Glasgow) and White (Paisley).

In the Victorian era, these events were manna from heaven, both to the troops and the civilian population.

Different sports thrived across Europe and the explosion in interest of football was notable between 1890 and 1910.

But in Gibraltar, at least, The Black Watch members were determined to retain their grip on the Governor’s Cup and they could hardly have managed it in any more emphatic a fashion than they did in 1892.

Rolling over the English on the rock

As Mr Terenti said: “The grand finale of the second edition of the Governor’s Cup took place on February 13 1892, in front of 7,000 spectators.

“The 42nd Black Watch faced the Royal Engineers and within seven minutes, the Highlanders, captained by Joe Duncan, were already winning 3-0, thanks to their short pass game, which was executed to perfection.

“(By the end), they won by a resounding 9-0.

“This was the second time in a row that the Highlanders had won the title without conceding a goal.

“The Gibraltar Chronicle, the local newspaper, once again highlighted the

popularity of the 42nd Black Watch among the civilian population.”

In the same year, plans were drawn up for a representative team from Gibraltar to face the cream of Andalusia, featuring players from Huelva, Riotinto and Sevilla, during what was designed as a celebration of the 400th anniversary of the ‘discovery’ of America by Christopher Columbus, whose first voyage set sail from Palos de la Frontera.

It promised to be a rip-snorting spectacle between the best players from the different Iberian organisations and would have attracted a massive crowd.

Sadly for The Black Watch contingent, however, the suspension of some of the commemorations meant the match was never played.

And, though they wouldn’t have known it then, their time in Gibraltar was about to be curtailed by events elsewhere in the globe.

One last shot at glory for Dundee

The Scots’ third and last success in the Governor’s Cup took place in January 1893 and, once again, the script followed a predictable pattern.

In this instance, The Black Watch were pitted against the 60th King’s Royal Rifles, but it was the holders who fired on all cylinders as they registered a 5-0 victory in yet another tournament where they didn’t leak any goals.

That brought the curtain down on their spell on the rock, with the battalion being re-assigned to the Cape Colony (in South Africa), where there would be sustained conflict with the Boers for many years.

However, they left behind a sport that has only grown in popularity in the last 130 years and, as Mr Terenti pointed out, the 1890s brought the foundation of such famous names as Barcelona FC and Athletic Bilbao FC.

No wonder the bond between Scotland and Spain and Gibraltar is so strong.

More like this:

The Black Watch: New book on the unsung heroes who went beyond the call of duty

Auchterarder WW1 soldier’s remains may have been discovered 105 years after death at Somme

Dundee war memorial: Why did the Law tribute to city’s fallen take seven years to build?