In the 1920s, it took far longer than the duration of the First World War itself to agree upon and erect a war memorial in Dundee.

Within two weeks of the signing of the Armistice on November 11 1918, the first discussions were held on a suitable memorial to the sacrifice of the city’s sons.

City leaders said “Dundee’s war record is noteworthy, and our war memorial must be worthy the record” – and they wanted it done quickly.

But it would be nearly seven years before Dundee’s memorial was unveiled, after the project was marred by a string of disagreements and delays.

How memorial sparked war of words

Despite saying there was “no time like the present” to erect a memorial, by 1919 it was still unclear as to what form it should take.

And Dundonians weren’t afraid to make their opinions known.

Citizens and leaders agreed a memorial was needed, but ironically, what was a monument to past sacrifice and future peace sparked a years-long war of words.

Many Dundonians wanted the memorial to be a children’s hospital, rather than a statue.

One citizen thought a hospital with a decorative dome bearing a stained glass depiction of the Battle of Mons would be an apt tribute to the fallen.

In a letter to the Courier he implored cityfolk to “think of the mud, the cold, the wet, the eerie darkness, the filth, the wounds, the sudden death, and then let your minds be made up that this memorial will be a fitting one to future citizens in their hour of youthful helplessness”.

Unsurprisingly, not everyone felt depictions of battle and horror in a children’s hospital was appropriate.

Other Dundonians called for a social centre or winter garden to honour the war dead, to be enjoyed by future generations.

Another proposition was a soldiers’ social club.

A grander suggestion was an imposing archway and colonnade on High Street as a frontage to a new city hall.

Debate over memorial site

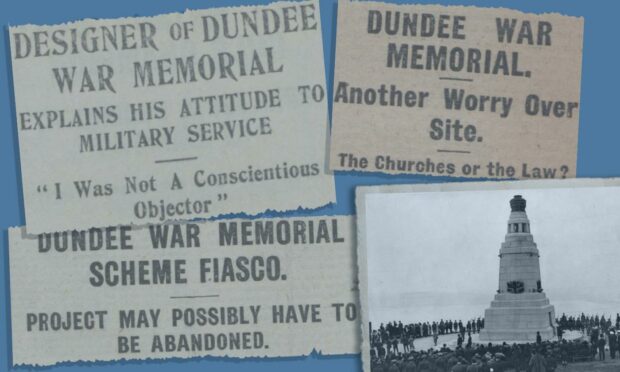

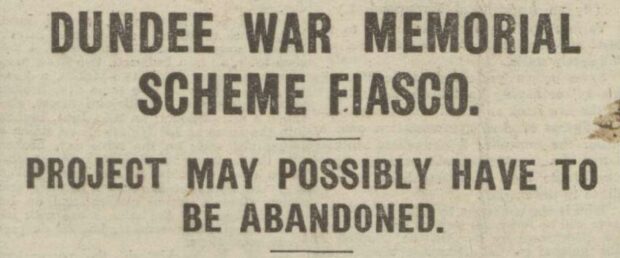

Come 1920, the project was branded a fiasco and faced being abandoned altogether.

No funds had been raised, while other schemes – a veterans’ garden and a Black Watch memorial – had begun in earnest thanks to Dundonians’ donations.

Lord Provost William Don pointed out that uncertainty over the memorial put people off parting with their cash.

Major Thomas Cappon, a Dundee architect and the city’s recruitment officer during the First World War, condemned his fellow committee members.

Having recruited many of the 4000 men who never returned to Dundee from the front, he perhaps felt a guilt and responsibility that a fitting memorial was erected.

He branded the committee “lethargic” and “disappointing”.

Still the in-fighting continued. By summer, members disagreed over whether the names of the fallen soldiers should be inscribed on the memorial.

City art master Thomas Dalgetty Dunn, calculated there were so many names to display, that the structure would need to be 40ft taller than Dundee’s Old Steeple.

It was finally agreed a monument was the most appropriate way to acknowledge Dundee’s fallen, along with a trust fund to help ex-servicemen – on the condition that conscientious objectors were barred from applying.

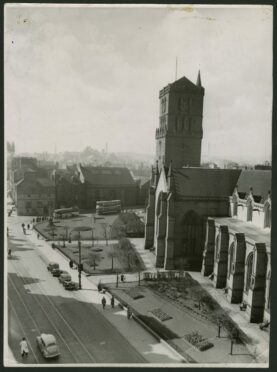

But progress was waylaid by another debate – should the memorial be located at the fountain site at Albert Square or the City Churches?

Albert Square was chosen, but residents were unhappy.

Robert Souter of Walton Street said: “It is now over two years since the Armistice, and the committee has not yet been able to decide what form the memorial should take.

“One wonders at businessmen suggesting such utter waste of money in removing a fountain for an undesirable monument.”

Calls to scrap ‘expensive, ugly’ memorial

By 1921, when other towns and cities were unveiling their memorials, the budget for Dundee’s was slashed from £60,000 to £15,000.

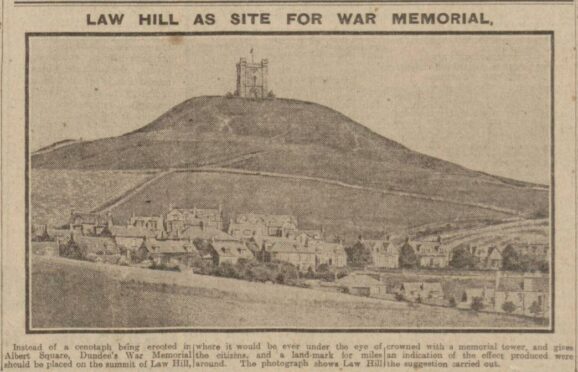

Albert Square plans had been shelved, instead Dundee Law was tentatively suggested.

But this was not without complications – plans had been made to erect an observatory on the prominent site.

Proposals included a dual purpose building providing “a splendid landmark” with panels bearing the names of the men who fell.

By summer 1921 the committee decided the Law was the place for a memorial, not an observatory, but couldn’t agree on a cenotaph or building.

Dundonians were keen to share their opinions.

Contacting the Courier, one resident urged: “First of all, abandon the idea of a ‘valhalla’ (hall of the fallen).

“Secondly, abandon the idea of a sculpture. Of all the arts, sculpture is often the most disappointing.”

Another irritated citizen wrote that the city’s unemployed should get on with building the memorial.

But not everyone was pleased about a memorial on the Law.

One war veteran said: “Are any of the reasons which demand the erection of a memorial met by its erection on top of an ugly old mound situated over a mile from the centre of the city, where hundreds of old people will never see it? I think not.

“If the committee have at the back of their minds the provision of a place for birds, or a sanctuary where some old fool will look through a telescope and chatter at the moon, then they are quite justified.”

Armistice Day 1922 came and went, and there was still no memorial.

Irate resident, Mr Irons of Strathmartine Road, called for the “expensive, ugly” Law proposal to be scrapped.

He added: “The Law Hill belongs to the community of Dundee. I am certain one-fourth of citizens are not in favour of the memorial.”

‘The Pimple on the Law’

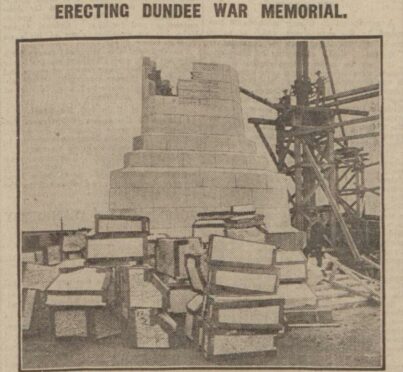

The Law remained the chosen location, but new arguments sprang up around the design.

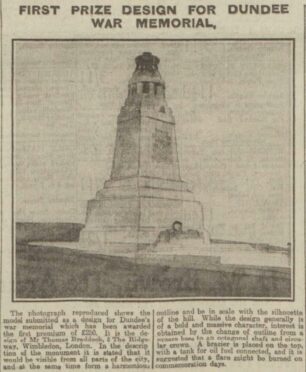

Initial designs weren’t big enough or grand enough, but the eventual winner was one that would be visible from all parts of Dundee.

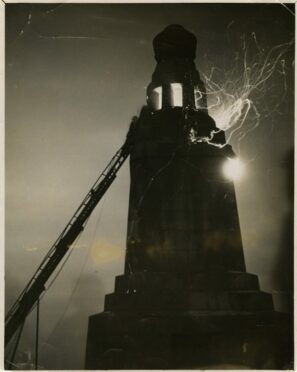

It was to have a square base and octagonal tower, a circular crown and a brazier on top for a beacon.

To convince citizens it was the best design, a full-sized model was built on the Law, but it was considered too squat.

After agreeing to make it taller, it seemed an end to the memorial saga was in sight.

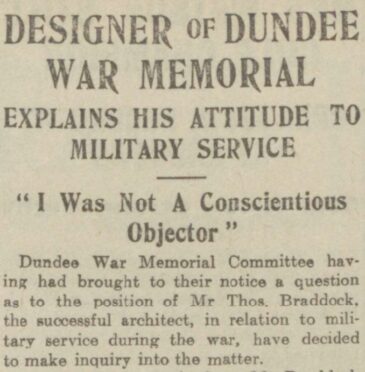

But an anonymous complaint was received that the London-based architect had been a conscientious objector.

An inquiry was launched, and designer Thomas Braddock was hauled before the committee.

Mr Braddock said although he had defended conscientious objectors, he was not one, and had been exempt from fighting on health grounds and was engaged in architectural war work.

Satisfied, the committee ploughed on.

But many Dundonians still objected to the memorial, and it was nicknamed “The Pimple on the Law”.

One said: “Public opinion is much adverse at both the style of ‘the pimple’ and its position.”

And by the the end of 1923 there was still no memorial – the committee had run out of money.

Furious Dundonians said citizens were “now apathetic regarding the war memorial”.

One man told the Courier: “From first to last this matter has been bungled.”

Continued controversy

But with tweaks to the design, the committee made the budget work – before being hit with a new controversy.

Plans were for granite to be imported from Norway for the build.

But there were widespread fears that the memorial would be built in German-owned granite.

The committee was forced to issue a statement: “Precautions are to be taken to see that German-owned Norwegian granite is not used in the construction of the memorial.”

Cornish granite was instead chosen at a cost of £10,348, and in January 1924, 450-tonnes of cement and metal were laid for the foundations.

The first consignment of granite – 93 pieces weighing in at 90-tonnes – was sailed to Dundee in April.

While progress was made in building the memorial, the committee fell out again over the inscription.

Councillor Barnes felt the plaque should be dedicated to “the service and sacrifice of all citizens”.

But city architect John McLaren argued: “It is essentially a memorial to the dead. The sacrifice of people still living might be very great, but this was a memorial to those who fell.”

After much debate, it was agreed the words should be: “To the memory of Dundee men who fell in the Great War, 1914-1918.”

Unveiling of memorial

It was decided the memorial would be unveiled on the Armistice in 1924.

But hopes of its grand reveal by General Haig in November were dashed – the bronze brazier was not going to be finished.

It was 1925 before a foundry in Cheltenham had completed the job, and the memorial was done by April.

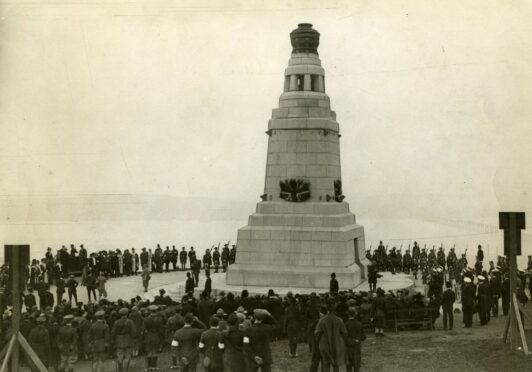

The unveiling date was May 16 with General Sir Ian Hamilton conducting the ceremony.

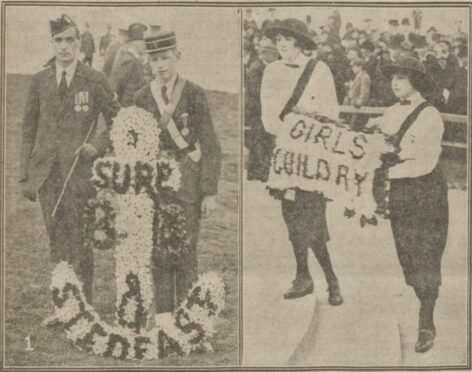

Despite the delays and derision, Dundee came together for the long-awaited memorial.

An estimated 30,000 people turned out at various points of the day to pay their respects.

Provost W Buist, chairman of the war memorial committee, was first to speak to the gathered dignitaries, troops, veterans, boys’ and girls’ brigades, scouts, guides and citizens.

He said: “Words fail to express the sense of the courage, gallantry, and self-sacrifice of those mourned, yet when memories were stirred, we see them again in all the glory of their youth, going forth in their endeavour to win a righteous and enduring peace.”

As the Union Jacks draping the memorial were released, the notes of “Lochaber No More” on bagpipes enveloped the Law.

General Sir Ian paid tribute to “the legend of the 4000 lads of Dundee”.

And spoke of “how they in the Great War went west, how they went off singing ‘Open the West Port and let us gang free’, and how the ‘Bonnets O’ Bonnie Dundee’ went down”.

He also spoke passionately about helping those who returned from the front line to Dundee as damaged souls “half-dead, upon the dole”.

When his speech ended, “the black-robed widow” of Black Watch leader Lieutenant-Colonel Harry Walker laid the first wreath.

She was one of many women dressed in black with medals and photographs pinned to their shawls and jackets.

After many wreaths had been laid “The Last Post” played; the silence afterwards broken only by a solitary lark which “trilled its clear-sounding hymn of praise”.

The memorial flare burned into the night as a “reminder to the new generation of the days of storm and stress, of heroism and of sacrifice”.

If you enjoyed this, you might like: