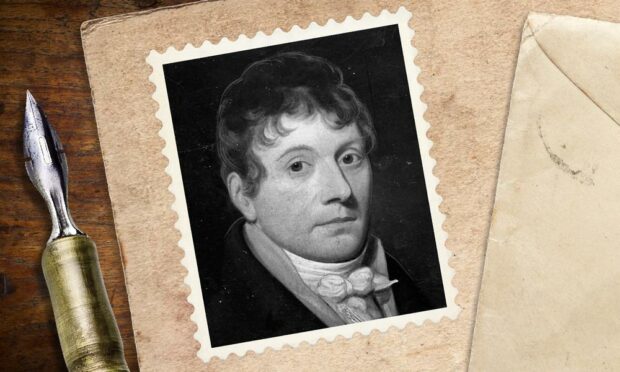

Arbroath-born James Chalmers played an important part in British postal history and produced the forerunner to the Penny Black.

Chalmers was born on February 2 1782.

He moved to Dundee in 1809 and became a printer, publisher and book seller, as well as a campaigner for postal reforms in the pre-stamp days when letters were charged on weight and how far they had to be carried.

According to his family, Chalmers first proposed in 1834, that adhesive stamps be adopted as a method of indicating pre-paid postage.

In his Castle Street office, he printed the very first stamps as we know them today, and worked out such things as the costs of a uniform penny post system and the best method of mail distribution.

His one mistake, according to his supporters, was in delaying for three years the official announcement of what he had achieved, by which time Rowland Hill had put down the idea on paper.

What happened?

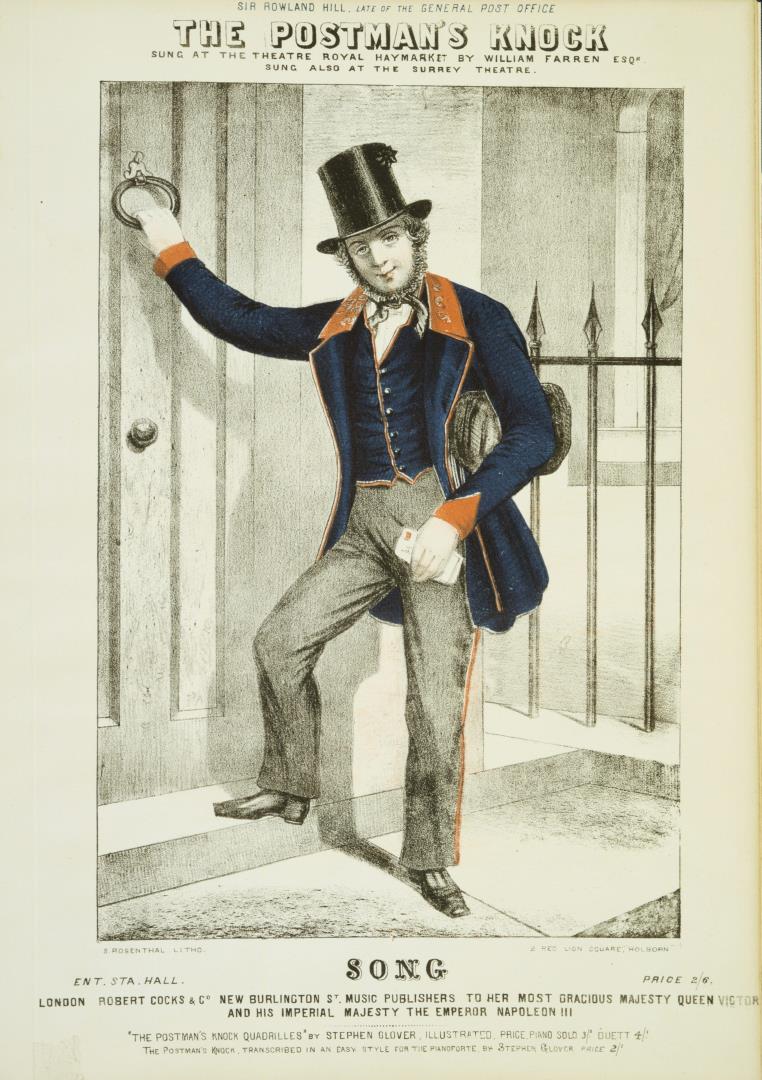

In 1837, Hill formulated a set of proposals for postal reform, published as Post Office Reform: its Importance and Practicability.

In 1839, the public were asked to submit their proposals for a pre-paid penny post to a Parliamentary Select Committee which was established.

A prize of £200 was offered for the best suggestion and £100 for the next best.

Over 2,600 designs and ideas were submitted, but Hill used his previously-published suggestion of using “a bit of paper just large enough to bear the stamp, and covered at the back with a glutinous wash”.

This suggestion was eventually to become the Penny Black.

Both wrappers and the Penny Black stamp were introduced in 1840, but it was Hill, as the man responsible for implementing the Penny Postage Bill of 1839, who was knighted by a grateful sovereign, received a public testimonial of £15,000 and was later buried in Westminster Abbey.

Chalmers was laid to rest in the ancient Howff in Dundee in 1853, and through the efforts of his son Patrick, his tombstone proclaimed: “Originator of the adhesive postage stamp which saved the penny postage scheme of 1840 from collapse”.

Argument and debate have raged down the years as the champions of each man have put forward their reasons for substantiating the claims of invention.

Postal historian Dr Norman Watson said: “As philatelists around the world confirmed that the Dundee printer was a pioneer, there was a cooling off in the public acclaim for Hill.

“But all it amounted to was a cut-back in the number of statues put up in his honour.

“Although there was no direct quarrel between Hill and Chalmers the arguments over who invented postage stamps continued to rage.

“Chalmers’ son Patrick was so incensed at the lack of recognition for his father that he gave up his brilliant career as a Far East merchant to put his fathers case to prominent philatelists.

“He lectured, wrote pamphlets and, at times, became embroiled in a heated debate with Pearson Hill, the son of Sir Rowland.

“The 12-year campaign cost him thousands of pounds and, some say, contributed to his premature death.”

The baton was passed to Chalmers’ granddaughter Leah Chalmers, who was diligent in her efforts to obtain recognition for her grandfather’s invention.

In 1939 she published a book entitled How The Adhesive Postage Stamp was Born.

In 1970 another book about Chalmers’ achievements was published by David Winter and Son, the Dundee firm which developed out of the printing organisation established by the inventor.

It claimed to set out “incontrovertible evidence” that Chalmers led the world in the development of stamps and urged a campaign for wider recognition.

In 1979 new stamps and first-day covers were issued by the Post Office commemorating the centenary of the death of Sir Rowland Hill which attributed the invention of the adhesive postage stamp to the Treasury official.

Champions of Chalmers were penny black-affronted at the Rowland Hill stamps, maintaining in apoplectic frustration that it was Chalmers, and not Hill, who first suggested the adhesive stamp system.

A James Chalmers Society was quickly formed to lick the opposition.

Following the fuss over the Rowland Hill special stamps of 1979, there was hope that a commemorative issue would mark the bi-centenary of Chalmers birth in February 1982.

Instead, the Post Office consented only to include his portrait on a £1.43 pre-printed stamp booklet which featured a brief résumé of his life.

It read: “In 1837, he submitted some examples of gummed labels to Robert Wallace, the MP for Greenock. Thus James Chalmers produced the first essays of adhesive postage stamps, the forerunner of the Penny Black.”

Dr Watson said the problem has been that the design for stamps which Chalmers is said to have produced in 1834 remains controversial.

He said: “It has never been verified and was never mentioned by James Chalmers himself.

“Its veracity, instead, relied on the 50-year-old recollections of three elderly former employees of Chalmers’ print house in Castle Street.

“This leaves us with Rowland Hill describing his plan for adhesive labels in February 1837, some five months before Chalmers submitted his plans.”

In 1983 the society succeeded in getting a motion, signed by 53 MPs, put before the House of Commons acknowledging Chalmers precedence.

The Encyclopaedia Britannica, after initially crediting Sir Rowland, changed their entries after studying the arguments in favour of Chalmers.

Dr Watson said: “Chalmers certainly produced in his Castle Street presses the first specimens for adhesive labels, which have been used as the means to convey post by every country in the world.

“He should also receive credit for using the town name and date to cancel stamps, which has become the most integral feature of every postal service in the world.

“And when he sent a copy of one of his two-penny stamps to the Secretary of the GPO in 1839, it became the first time that an envelope bearing an adhesive stamp ever went through the mails.”

Dr Watson concluded: “For a time it seemed that the whole world accepted Chalmers as the inventor of stamps – apart from the British Post Office.”

However, in Dundee and in his native Arbroath, Chalmers remains “the inventor of stamps”.

You might also like:

Muhammad Ali: Was ‘The Greatest’ made in Arbroath?

Going off the rails: The Tayside and Fife branch lines lost to the Beeching cuts

Sunset Song: Lewis Grassic Gibbon’s portrait of man and the Mearns is 90