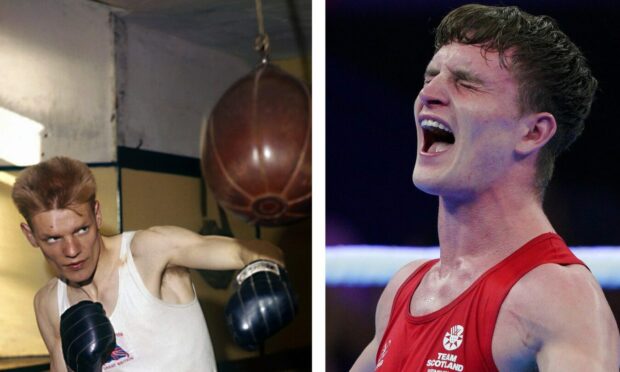

Dick McTaggart rolled back the years as he relished fellow Dundonian Sam Hickey surging to a gold medal at the Commonwealth Games in Birmingham.

It’s long ago and far away, when major sports events were relatively low-key affairs compared to the global extravaganzas into which they’ve developed, that McTaggart first displayed his power, precision and technique to enter the boxing pantheon.

But this Olympic champion back in 1956, who followed up that victory with another gold in the Commonwealth Games in Cardiff in 1958, isn’t one of the grouches inclined to complain that modern life is going to hell in a handcart.

On the contrary, he has been in his element surveying the success of the Scots in the ring at Birmingham’s NEC.

As he gazed on while the 22-year-old Hickey edged out Australia’s Callum Peters in a terrific middleweight showdown, which could have gone either way, McTaggart was with his compatriot in spirit as the contest ebbed and flowed.

And he was thrilled when the referee eventually lifted the Lochee fighter’s arm to proclaim he had won the epic bout.

McTaggart, 86, has been involved in coaching previous generations of Commonwealth Games stars from his homeland and was pictured on the team bus at the 1986 event.

So he appreciated the dedication and commitment required by the likes of Hickey to prepare for a series of gruelling back-to-back challenges on the international stage.

He said: “I watched Sam’s contest and for someone else from Dundee to win the Commonwealth gold is just fantastic.

“Sam looked really good and I am really proud of him”.

That’s not bad from a man who used to spar with Muhammad Ali and knows almost everybody who’s anybody in the fistic arts during the second half of the 20th Century.

Indeed, the Scot was originally nicknamed “Dandy Dick” by boxing commentator Harry Carpenter.

And, although it’s more than 65 years since the smart-as-paint Dundonian surged to Olympic glory, there’s still something of the blithe boy about McTaggart.

For many, this character is his city’s greatest-ever sportsman and there are distinct similarities between him and Aberdeen-born Denis Law.

Both emerged from working-class backgrounds and have laboured tirelessly at the grassroots to encourage youngsters to kick a ball or hit a punchbag.

And both have had statues sculpted in their honour, yet remain as down to earth and approachable as they were at the height of their powers many moons ago.

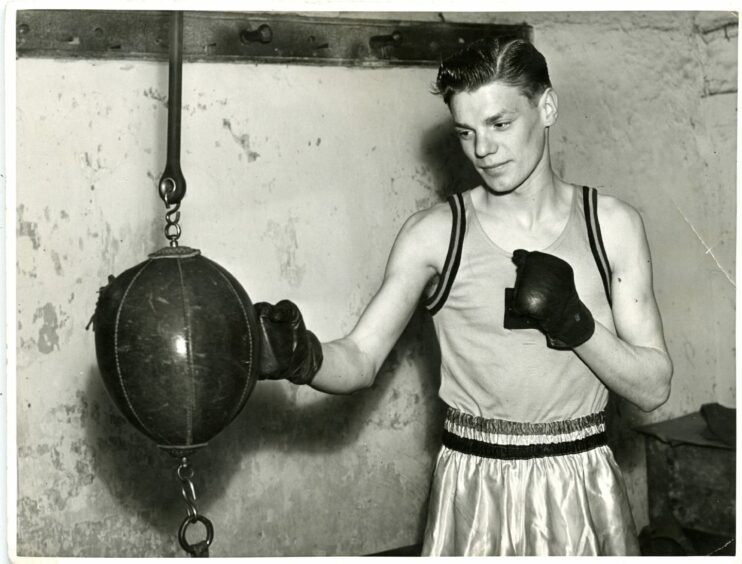

Dick thrived in the sport in the 1950s

It was another time, another place when the 21-year-old McTaggart travelled to Melbourne on his maiden Olympic mission in November 1956.

And it’s little wonder that he was glad to arrive in Australia after a gruelling journey that took five days and included a stop-off in Honolulu, which was a place of exotic beauty for the boy from a Dens Road tenement building.

This was long before there was Lottery funding or any semblance of Team GB, but Dick – a gifted pugilist with a style and technique which impressed the cognoscenti – had no intention of simply making up the numbers.

He recalled: “People had told us before we left that we should go there and enjoy ourselves, with the Olympic motto being all about taking part.

“But I wasn’t interested in going all that way just to enjoy myself. I wanted to get a medal. I didn’t care what colour it was, as long as I got a medal.”

Soon enough, he was on the charge, bewitching, bewildering and beating opponents and although he was the underdog when he met Harry Kurschat, the reigning European champion from Germany, in the final, McTaggart wasn’t interested in second best.

He said later: “I hadn’t known any of the other lads I had fought, but everybody had heard of Kurschat and he was good.

“But I had him down twice in the first round and thought it was all over.

“However, credit to him, he got up twice and came back strong. But I won it clearly enough, in the end, and it was just such a fantastic feeling.

“I had collected my gold medal and wanted to go away and celebrate, but I was told by the officials: ‘There might be a wee surprise for you’.

“Then, later on, they announced I had won the Val Barker Trophy (awarded to the most stylish performer in all the weight divisions at the Olympics) and that meant more to the British delegation than any of the other medals and prizes because no British competitor had ever won it before.

“I reckon that I must have filled the trophy up with champagne about 150 times that night as everybody celebrated.”

McTaggart’s exploits gained him instant fame and there were plenty of offers to turn professional, but this shrewd individual has always worked on the basis that he would forge his own career path and trust his instincts.

Besides, he was thrilled when he eventually returned home and discovered that his mum and dad were waiting for him in London and the pride in their eyes at his achievements meant more than any pound signs.

He recalled: “They had never been on a plane before, but they had flown down to meet me specially.

“Then, when we got the train back to Dundee, thousands of people in the city turned out on the streets to welcome me home. It brought tears to my eyes.

“Fellow boxers John McVicar and Peter Cain hoisted me up on their shoulders and carried me up the stairs out of the railway station.

“And then, there were thousands of people who had lined the streets and were cheering. I couldn’t believe it.

“We got in an open-top motor and made the journey up to our house at Dens Road. It was unbelievable, but it was the greatest thing in the world.”

Moving on to meet The Greatest

It was just a few weeks before Christmas – he won his gold medal on December 1 – when McTaggart was acclaimed as the toast of his community and was presented with a Rolex watch by the city fathers in Dundee.

But he wasn’t finished with the Games or following his single-minded route to success.

Thus, when he ventured to Rome for the 1960 Olympics, plenty of pundits predicted he would defend the title he had secured four years previously.

However, these global Games regularly throw up some controversial outcomes and he had to be content with a bronze in the Italian capital after losing in the semi-finals to eventual champion Kazimierz Pazdzior of Poland.

He was pretty stoical. “I felt I won the fight and it was really disappointing. But looking back now, to get a medal of any sort wasn’t bad.”

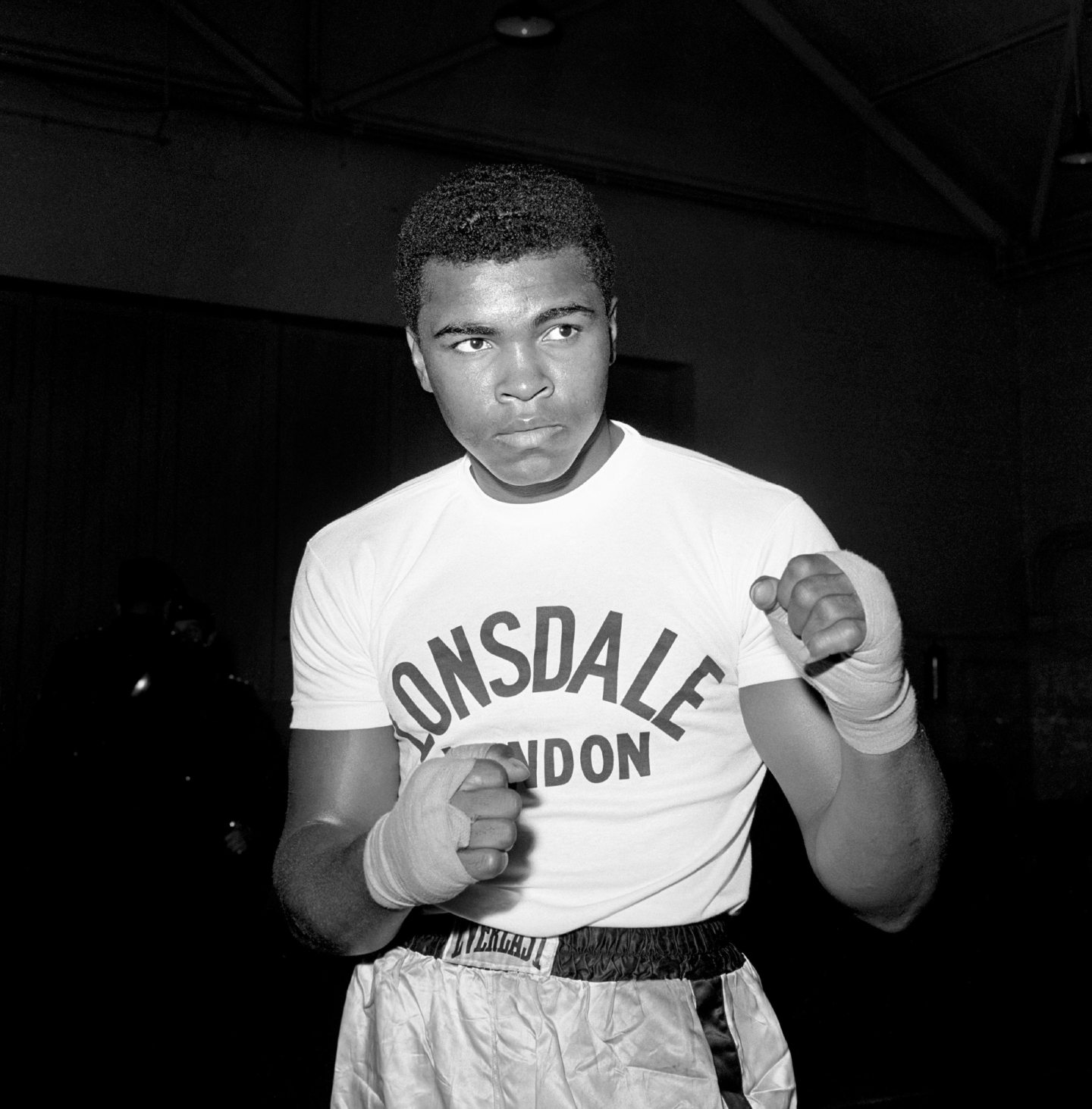

And it offered him an opportunity to meet and break bread with a young man called Cassius Clay, who was poised to become a superstar in the next decade.

McTaggart’s reputation as the best amateur on the planet – he was so described by the aforementioned Carpenter – meant he was welcomed for a nosh-up with the US team members and gained the chance to find out if the hype about Clay was justified.

Yes, it was. Yes, it was with a vengeance.

As he said: “The Americans invited me to eat with them in their canteen.

“I was introduced to this big lad Cassius, whom everybody had been talking about, and even then, he was shooting his mouth off and telling everybody he was going to be the heavyweight champion of the world.

“He was great fun to be around, though, he had so much talent and charisma and I thought he should have got the Val Barker trophy at those games.

“He was also a gentleman and, when I watched him fight, it was obvious that he had the ability to back up all the things he was saying.”

When Muhammad Ali died in 2016 after years of suffering from Parkinson’s disease, it was a reminder of the dangers for any boxer who takes sustained blows to the head.

McTaggart had noticed he was increasingly feeling the pain by the mid-1960s, not long after his third and least successful appearance at the Olympics (in Tokyo).

So he wisely stepped away and transformed himself into a coach, a mentor, a motivator and inspiration for so many youngsters in his homeland.

But he was as star-struck by Ali as anybody else. And, after the American’s death, Dick said: “He was a class apart. You could see it. He was so special!”

He has always been a gentleman

All those years later, the wiry Scot who won 610 of his 634 amateur bouts remains the only man from his country to strike gold in Olympic boxing.

He was thrilled at the reception and has derived a huge amount of satisfaction from the creation of such enduring legacies as the Dick McTaggart Centre in his beloved Dundee.

There are no regrets about remaining an amateur, even though he was offered £1,000 to turn pro by one promoter in the 1950s, which “was a fortune in these days”.

He said: “I enjoyed boxing, but I never wanted it to become my job. I knew that I didn’t have many brains, but I wanted to keep the ones that I had.”

It sounds like he made a smart move – as always!

More like this:

The ecstasy and embarrassment of Liz McColgan and Robert Maxwell at the 1986 Commonwealth Games

Conversation