“Remember me to all friends”.

Fife doctor Harry Goodsir signed off with those words in his final letter to his father before leaving Disko Island off the western coast of Greenland in July 1845.

“Remember me,” were Hamlet’s father’s ghost’s last words.

We know now that Harry would never see his family and loved ones again.

Harry’s last parting was among the collection of personal letters related to the doomed Franklin expedition which have been brought together for the first time.

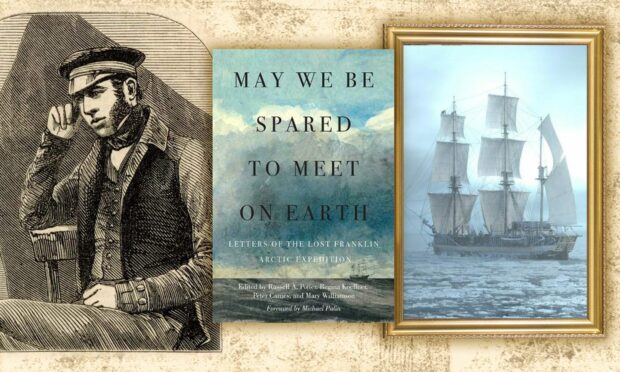

May We Be Spared To Meet On Earth is a new book that documents the letters written by Sir John Franklin and his men from aboard HMS Erebus and HMS Terror.

Can these letters shed light on one of history’s most enduring mysteries?

Harry’s father, John, from Largo, spoke of his “great misgiving” and initially looked upon the voyage as a “fearful hazard” when writing to his son in June 1844.

His hunch proved eerily correct.

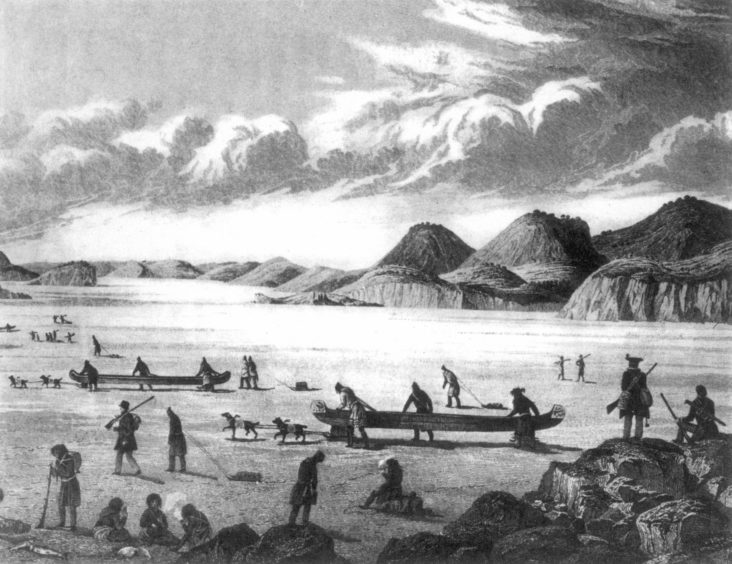

Franklin departed Britain in May 1845 in command of Erebus and Terror to find the Northwest Passage, which was a short cut between Europe and Asia.

Harry was one of at least 15 Scots on the expedition including Dundonians William Bell and William Shanks, David Leys from Montrose and Robert Ferrier from Perth.

The ships set sail from Greenhithe in Kent on May 19 1845.

The Erebus and Terror made their final stop before the Atlantic crossing at Login’s Well, Stromness, Orkney, for water and supplies.

Harry was assistant surgeon and naturalist on HMS Erebus.

The ships docked at Disko Bay where some of the crew sent letters home to their loved ones, which was the last time anyone in Britain heard from the explorers.

The ships were last seen in Baffin Bay in the Arctic three weeks later and after this they vanished without a trace and all 129 men on board perished.

The fate of the crew fascinated Victorians and inspired the acclaimed Ridley Scott TV series The Terror, which gripped viewers in the UK and America.

May We Be Spared To Meet On Earth provides new insights into those personalities.

Russell Potter, Peter Carney, Regina Koellner and Mary Williamson (Franklin’s great-great-grand-niece) edited the book, which includes a foreword from Sir Michael Palin.

Dr Potter said: “Early on, we decided to arrange the letters in chronological order, so that the various phases of the expedition, from the initial planning to its sailing to the last mail bag, would form the book’s intrinsic structure.

“What surprised us was not simply how many letters we found – we’d started out with somewhere around 70 and the final count came to 195 – but the ways in which, when read in sequence, they gave a detailed and vivid sense of the men’s lives and personalities, as well as their evolving sense of the expedition’s mission and meaning.

“The crew was, on average, a young one, and many of the letters are to parents and siblings; we learn innumerable slight – and yet significant – things such as them and their families.

“We learn of how Harry Goodsir furiously lobbied to be appointed the expedition’s naturalist, as well as of his need to borrow some of the required silverware from his family.

“One thing you find in his early letters is how his close-knit family worked, both to help him secure his appointment to the expedition, but also in more humble ways such as finding a job for his brother, Robert.”

The book is also illustrated with drawings and charts including an engraved plate of natural history specimens based on sketches made on board by Dr Goodsir.

His considerable expertise in specimen illustration was demonstrated daily on a table provided for him by Sir John Franklin in his quarters.

Fast-forward to 1846, which slipped away with no sign of either ship and no word from the Erebus or Terror parties, and it became clear that something had gone wrong.

Since the expedition was equipped with three years of provisions, the Admiralty in London did not send out rescue missions until 1848.

Franklin expedition book tells how letters were sent into uncertainty

As the realisation dawned that something was amiss, heartfelt letters to the missing from the men’s families were sent into uncertainty with those search expeditions.

They were returned unread.

Among them a letter from Harry’s sister Jane in April 1849 where she informs him of painful tidings and the death of both his father John and brother Archie.

In total, around 50 rescue missions were launched to find Erebus and Terror, and these expeditions covered new ground, added more details to the rapidly evolving maps, and helped define the territory of Canada.

Almost a decade later Lady Franklin decided to send out a final expedition from Aberdeen to clear up the great Arctic mystery, setting sail on June 30 1857.

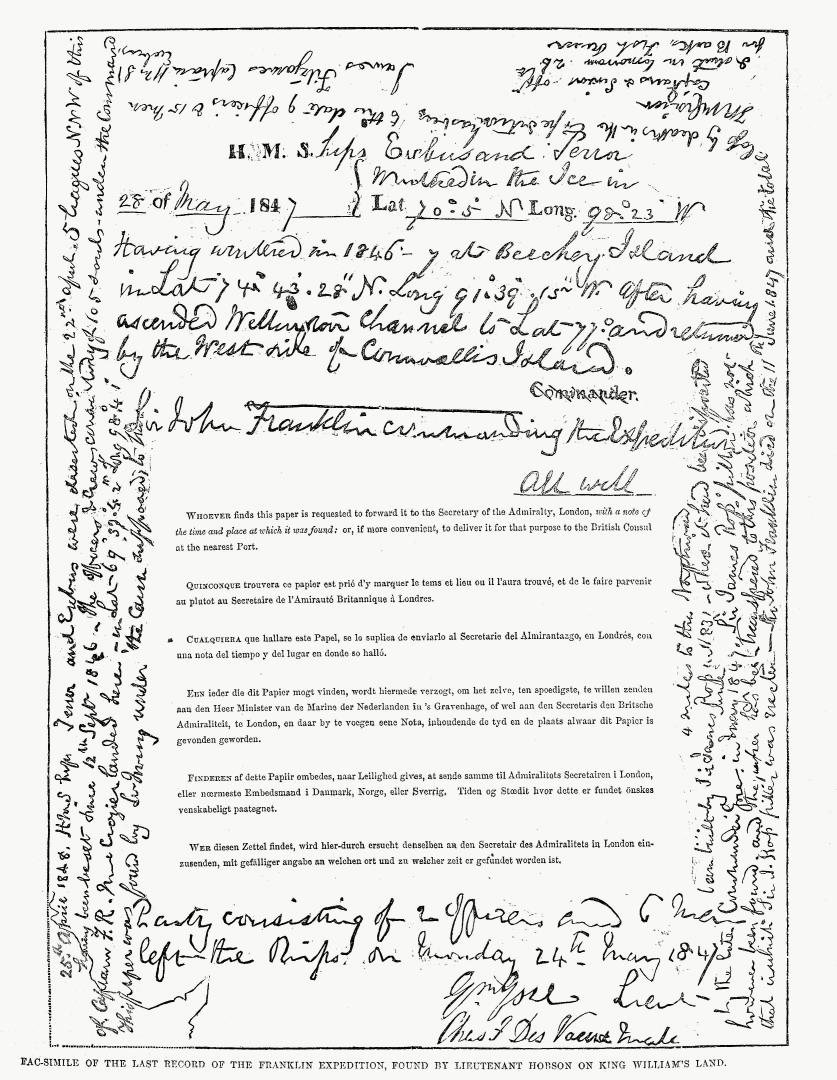

Two years later, on King William Island – in what is now Nunavut in the Canadian Arctic – they discovered written proof of the death of Franklin and of several officers and men – but that was the last information found.

A hundred survivors were setting out on foot after the record was deposited in the cairn and all we know is that none of them made it to safety.

The record increased the mystery.

So why is there still so much interest in the Franklin expedition after all these years?

Dr Potter said: “Well, everyone loves a mystery, especially one that has proven so difficult to untangle for so long.

“I also think that there’s a great public yearning for heroic figures, a sense that there was a kind of high character or nobility of spirit in the explorers of yore.

“And the fact that Franklin and his men, despite that, despite their fine ships and ample stores, were reduced to privation and ultimately cannibalism makes this noble story into a noble tragedy – the best kind – and has only served to increase its appeal.”

Dr Potter said among his favourite letters was Harry’s boast from Disko Bay of having climbed the top of an iceberg “to get a good knowledge of the structure”.

“He claims he’s done it in the name of science,” said Dr Potter.

“I suspect he also fancied being the king of the mountain, as it were!”

Another favourite is the correspondence of Aberdonian James Reid to his wife, which were gentle and romantic and also extremely honest about the risks of the voyage.

Dr Potter said he knew Franklin and his men sent letters home up to their arrival in Greenland in July 1845 but they hadn’t realised the “volume and richness of that correspondence” until they started work on the project around six years ago.

Mary Williamson’s family collection of letters was one key source but Dr Potter said most of the correspondence was found by combing through archives around the world.

They were helped by descendants and amateur sleuths of every sort along the way!

Dr Potter said: “Our hope is that, to the fullest extent possible, readers will feel as if they are just over the shoulders of these writers and can have an uninterrupted experience of their collective testimony.

“You don’t have to be a historian or a specialist to enjoy this book.

“Despite its size, I hope that it reads quite easily and well, and that the notes – which are kept at the end – will satisfy readers’ curiosity about all the particulars.

“It’s almost a sort of epistolary novel – albeit one with many writers – and in which the other half of the correspondence must ever remain unread and unknown.”

- May We Be Spared To Meet On Earth is out now.

Conversation