It reads like the ultimate geography field trip.

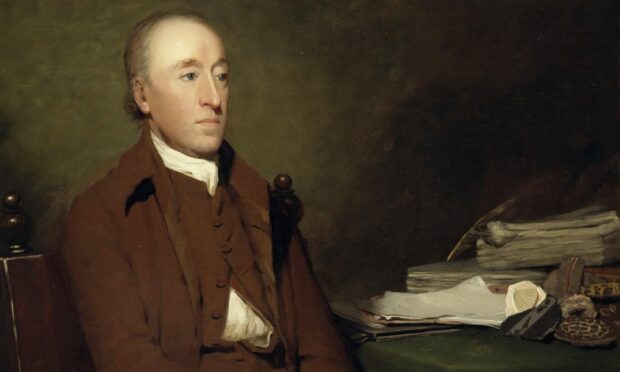

Hiring a boat and taking a trip along the coast to Siccar Point, near Eyemouth, in 1788, James Hutton scanned the coastline then stopped to inspect horizontal rock strata resting on top of vertical strata.

He explained to his friends how these gradual geological processes could only have happened over untold millions of years.

Today Siccar Point is a place of pilgrimage for geologists from all over the world.

The visit by Hutton, who is regarded as the father of modern geology, led to a profound change in the way the history of the Earth was understood.

Hutton used the evidence from Siccar Point to decode Earth processes and to argue for a much greater length of geological time than was popularly accepted.

Hutton’s research reset the world view of the Earth’s processes and made possible other major theories such as continental drift and the theory of evolution.

The concept of ‘deep time’ emerged with the recognition that the geological processes occurring around us today have operated over a long period and will continue to do so into the future.

But despite the significance of Hutton’s findings, why has this key figure of the Scottish Enlightenment often been overlooked?

Research for new book

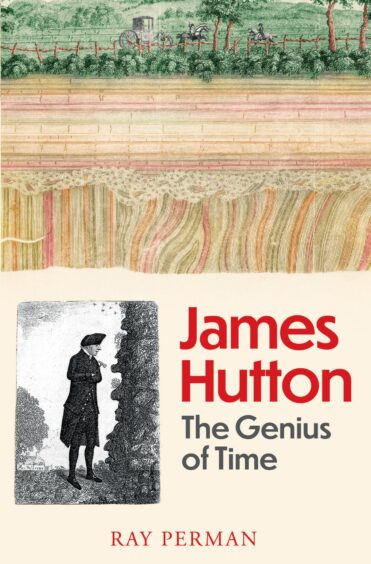

One man who admits he knew very little about James Hutton is former Times and Financial Times journalist Ray Perman.

After retiring from newspapers and his own magazine company which he ran for 15 years, the now 75-year-old became involved in various non-executive roles.

He was chair of the James Hutton Institute and is a fellow of the Royal Society of Edinburgh, of which Hutton was a founder member.

Having now written a book called James Hutton: The Genius of Time, he reveals that “probably the most relevant” development for him came when he was recruited to form what is now the James Hutton Institute at Invergowrie and Aberdeen.

This brought together the Scottish Crop Research Institute and Macaulay Land Use Research Institute under one new identity, with the new name chosen by the staff following a competition.

In an interview with The Courier, Edinburgh-based Mr Perman says he had previously “only vaguely” heard of James Hutton. He knew he was “something to do with geology”.

But the more research he did, the more he realised the many other aspects to his life.

‘Overshadowed’ by friends

Hutton was in his time a doctor, a farmer, a businessman, a chemist yet he described himself as a philosopher – a seeker after truth.

A friend of James Watt and of Adam Smith, he was a polymath, publishing papers on subjects as diverse as why it rains and a theory of language.

He shunned status and official position, refused to give up his strong Scots accent and vulgar speech, loved jokes and could start a party in an empty room.

Yet much of his story remains a mystery.

His papers, library and mineral collection all vanished after his death and only a handful of letters survive.

He seemed to be a lifelong bachelor, yet had a secret son whom he supported throughout his life.

“I think there are a couple of reasons why Hutton has been overlooked,” says Mr Perman.

“One, he was overshadowed by his closest friends really.

“He was a great friend of Adam Smith the economist.

“In fact he was one of the executors of Adam Smith’s will.

“But the other reason is Hutton was a very simple man. For example, he never gave up his broad Scots accent.

“Other people like Adam Smith went to elocution lessons so they could speak the King’s English.

“Hutton never did that –he was quite happy speaking broad Scots.

“So when he wrote, although he wrote in English he wasn’t a fluent writer and his books are really quite difficult to read.

“They are full of digressions, unnecessary descriptions and sometimes it takes you a long time to penetrate to what he was meaning.

“I think that led to his books being undervalued and perhaps not being as widely read as they should be.”

Missing information

With so much correspondence about Hutton’s life missing, Mr Perman says this made writing about him “very difficult”.

By contrast, with Adam Smith and Sir David Hume, who is another very well-known giant of the Scottish Enlightenment, there are literally hundreds of letters and papers either written by them or about them or to them.

But for Hutton there is only a “handful” of surviving letters. A vast collection of papers that existed after his death “completely disappeared”, as did his library.

Mr Perman would love to find the books from Hutton’s library to know what his influences were.

However, his own view is that Hutton read very widely and was very well aware of what was happening in geological research all around the world.

“I’ve traced two books which were owned by him – one is in the University of St Andrews Library and the other is in the Royal Botanic Gardens in Edinburgh,” says Mr Perman.

“So I’m hopeful of trying to find more in the future to try and get a better picture of Hutton’s life.”

Perthshire geology

Some of Hutton’s earliest discoveries took place in Perthshire in the summer of 1785 when he visited Glen Tilt and other sites in the Cairngorms.

Here, he found granite penetrating metamorphic schists in a way which indicated that the granite had been molten at the time.

He discovered similar penetration of volcanic rock through sedimentary rock at Salisbury Crags in Edinburgh, next to Arthur’s Seat.

Hutton, who believed in God, wasn’t the first to challenge the Biblical orthodoxy of the time.

Some had started to challenge the orthodox views of James Ussher, 17th century Primate of All Ireland, who’d published a detailed academic tome explaining that “creation” happened at around 6pm on October 22, 4004 BC.

One hundred years on from Ussher, many scientists theorised that rock was laid down in strata at the bottom of the sea and this seemed to fit well with the idea of Noah’s flood.

But while several scientists began to challenge the idea of a 6000-year-old Earth as being too short, only Hutton realised that what they were really talking about was unimaginable eons of age.

“He never put a figure on it,” says Mr Perman, “but we now know the Earth is four billion years old.

“To Hutton, that was unimaginable ages, because the processes he was describing – of strata being laid down in the sea, the earth slowly being pushed up by heat from the centre of the Earth until they formed dry land, then mountains being washed by the rains and battered by the winds and broken by the frosts, slowly dissolving down and being carried by the rivers back into the sea – that sort of process he described could not happen in thousands or millions of years.

“It took hundreds or thousands of millions of years to occur.

“That was Hutton’s big break through.”

Who was Hutton ‘the man’?

Perman’s book uses new sources and original documents to bring Hutton the man to life and places him firmly among the geniuses of his time.

Information pieced together includes letters from his close friends – the chemist Joseph Black and James Watt the steam engine builder.

There’s mention of Hutton’s illnesses, and at a time when Watt was depressed, Black says in a letter to Watt how he wishes he could “give you a dose of our friend Hutton’s company because he would cheer anybody up”.

“Hutton was not a dour man at all,” adds Mr Perman.

“He loved a party. He was very amusing. He loved to joke, and so we know a bit about his character.

“We know that he didn’t put on airs and graces, he never took elocution lessons. Unlike other fashionable men of the time, he never wore a wig. He didn’t bother covering up his baldness.”

Illegitimate son

But even his close friends at the time did not know that he’d had a relationship with a woman and had an illegitimate son.

It wasn’t until after his death in 1797 that a man tuned up, thought to be around 50, and said ‘my name’s James Hutton and I’m the son of the late James Hutton’.

“It turned out he was,” adds Mr Perman.

“He had six children of his own and James Hutton had supported him financially, and his children, throughout their lives.

“So the big question is who was the mother, why did James Hutton not live with her or marry her, and what was the story there?

“Many people have tried to solve that riddle and I’m ashamed to say I’m among the failures.

“There are plenty theories. But I’m afraid there’s very little evidence.”

Where to find the book

*James Hutton: The Genius of Time by Ray Perman, published by Birlinn, is out now, £25.

Perthshire geologist completes book series exploring Scotland’s ‘last untold story’

Conversation