Strewn across a remote beach in the Canadian High Arctic, the splintered remains of the Dundee-crewed whaling ship Nova Zembla provide an amazing insight into the fate of the vessel that sank in September 1902 and remained lost for 116 years.

Now, materials from two expeditions that helped locate and identify the vessel in 2018 and 2019 have been donated to the McManus in Dundee.

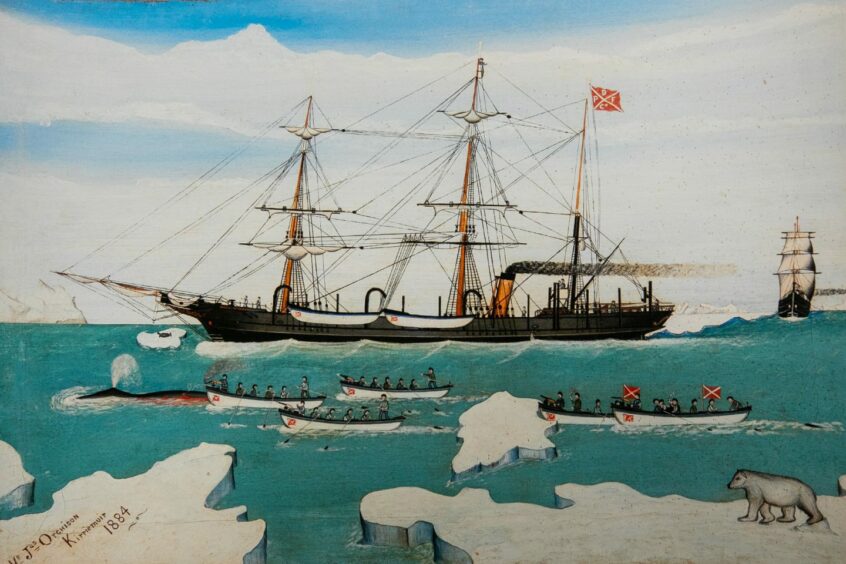

Tynemouth-raised researcher Dr Matthew Ayre of the Arctic Institute of North America at Calgary University, Canada, travelled to Dundee to hand over items including photographs, a seven feet long aerial map of the wreckage site and a copy of a Nova Zembla painting from 1884.

He met with Julie McCombie, Social History Curator (Cultural Services) at Leisure & Culture Dundee, who said: “We are pleased to accept this material in to the museum’s recognised whaling collection.

“The collection highlights Dundee’s place as one of Scotland’s premier whaling ports at the end of the 19th century.

“The finding of the wreck of the Nova Zembla, one of Dundee’s very own fleet, was an exciting occurrence and one which we are delighted to record within the city’s collections.”

Discovering Nova Zembla

Until 2018, historical climatologist Matt had never heard of the Nova Zembla.

The Sunderland University geography graduate, who obtained his PhD in 2016, was studying the surviving ships’ logbooks of the British Arctic whaling trade to learn about changes in sea ice for his post-doctoral research.

The logbooks also provided an “amazing window” into the lives of those who ventured to the icy edges of the known world.

It was in March 2018 while working on the logbook of the Diana’s 1902 voyage from Dundee to Baffin Bay, however, that he came across a single entry that came to dominate his thoughts.

It read: “One of the Nova Zembla’s boats came alongside and reported to us that the Nova Zembla was ashore a little to the southward, and that water was up to the ‘tween decks’.”

Intrigued to know more about what had happened and whether the wreck was still there, he diverted the course of his research – a pique of interest that would ultimately lead him to The Courier newspaper archives, then on to the perilous waters of the Canadian Arctic where, after 116-years, he discovered the lost wreck itself.

Partnering with the Royal Canadian Geographical Society, Matt teamed up with fellow researcher Dr Michael Moloney to search for the wreck.

Guided by the old Dundee newspaper reports which gave eyewitness accounts of the Nova Zembla’s plight, they had almost given up when, just hours before they had to leave, they spotted something that looked suspiciously like driftwood on the beach.

Buoyed by renewed expectation, they launched their drone to take photographs.

But almost immediately it was clear this was no driftwood – it was the mast of a ship complete with iron fittings, alongside a bit of bow, block and tackle, a yardarm and a rib timber with iron rivets– very clearly pieces of a sizeable wooden sailing ship.

An ROV survey also caught them a glimpse of an anchor and chain on the seabed.

Returning in summer 2019 – and this time with the right permits to go ashore – they discovered thousands of items strewn across the beach ranging from a 60 feet section of hull sticking out of the sand to the masts still intact on the beach.

They had indeed found the wreck of the Nova Zembla – the first British whaling ship wreck to be discovered.

Impact of Scottish whaling

Since May 2020 when The Courier last spoke to Matt about his research, his work has “evolved quite a lot”, he reveals.

Not only did the Covid-19 pandemic scupper plans by National Geographic to make a documentary about the expedition, his archaeologist colleague has since changed jobs and moved away to be closer to his family on the other side of Canada.

But what Matt has continued to do is more research around the legendary Dundee-connected Inuit Olnick and the second whaling ship wreck that’s in the area, the Eagle.

He’s also working closely with an Inuit youth organisation.

Pond Inlet youth are set to explore the impact Scottish whaling had on Inuit culture and history.

Ikaarvik, a non-profit organization based in Pond Inlet, received funding from the Trebek Initiative, which gives money to projects that protect the environment, culture and history.

It’s a joint fund by the National Geographic Society and Royal Canadian Geographical Society.

The idea of studying the history of whaling in Nunavut came to Ikaarvik when it worked with the Nova Zembla research team.

Matt’s team met with Ikaarvik representatives and learned about how whaling had defined “modern Inuit culture,” such as square dancing, clothing materials and Bannock-making.

The organisation decided it would be empowering for youth to be able to research their own history.

Matt was amazed to learn how many Inuit are descendants of Dundee and wider Scottish whalers.

Conscious that the McManus in Dundee already had the only surviving document from the Nova Zembla – the surgeon’s journal from 1884 – he was keen for a “little bit” of the ship to come home to Dundee through the expedition materials.

However, he hopes that one day he might be able to accompany some of the Inuit youth over to Dundee – and Shetland – to trace their cultural, and in some cases ancestral, roots.

As part of this new project, the youth have been sharing historical photos of Inuit and whalers from the McManus with their community.

Matt is heading up to Pond Inlet in November to help with the next stage where they will be interviewing elders to collect oral histories on their connection to the Dundee whalers.

“This is the thing I’d really like to see come out of this and certainly my work with the Inuit communities up there is to essentially re-establish this connection,” he said.

“There was a really strong connection between Scotland and the communities on Baffin, which was really started and maintained by the whaling trade then sort of taken over by the Hudson’s Bay Company when whaling ended.

“But there’s this really interesting period of time before there was true colonial influence in the Arctic.

“The whalers were never there to exploit the Inuit. They were there to catch the whales.

“There’s almost this organic relationship that develops. Trade and friendship. A mutual respect.

“Which is why they are so fondly remembered. The Hudson’s Bay Company is not talked of in the same fondness, which is really interesting.”

Whaling industry: past and present

Today whaling is still a central part of Inuit life, necessary for subsistence, but also culturally important.

While commercial whaling is now unacceptable, it remains distinct from indigenous subsistence whaling.

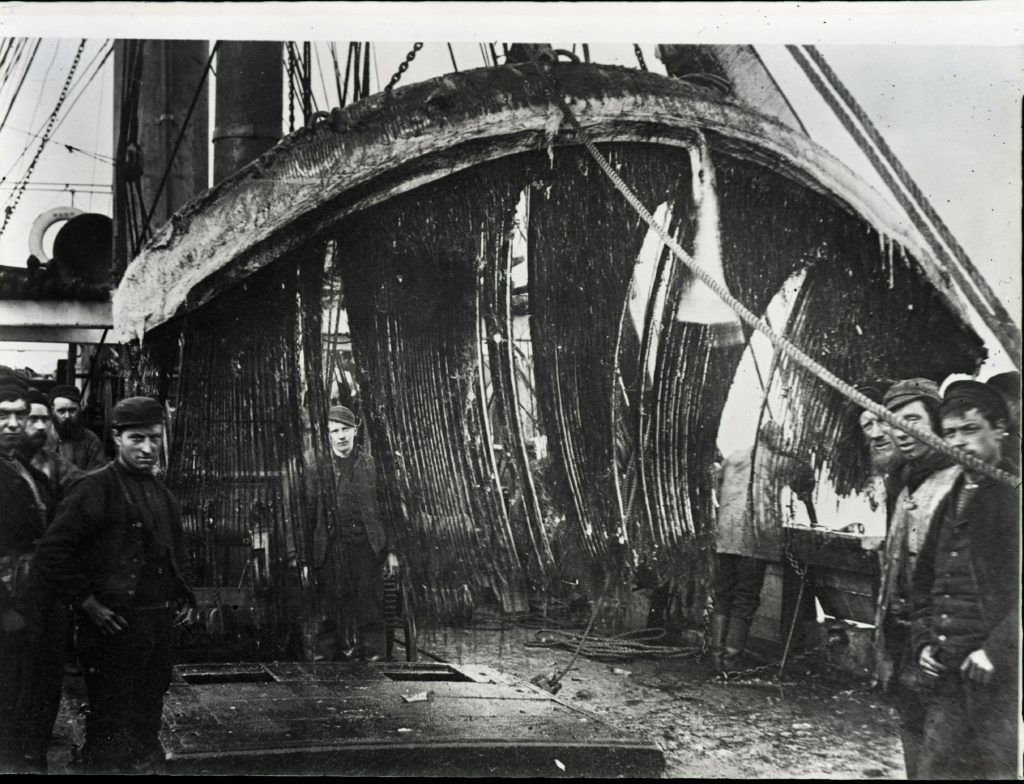

Between the 18th and 20th centuries, Dundee whalers were at the forefront of a lucrative industry that yielded tons of valuable oil to lubricate the industrial revolution. The Baleen, known as whale bone, was also used to form the supports of corsets and petticoats.

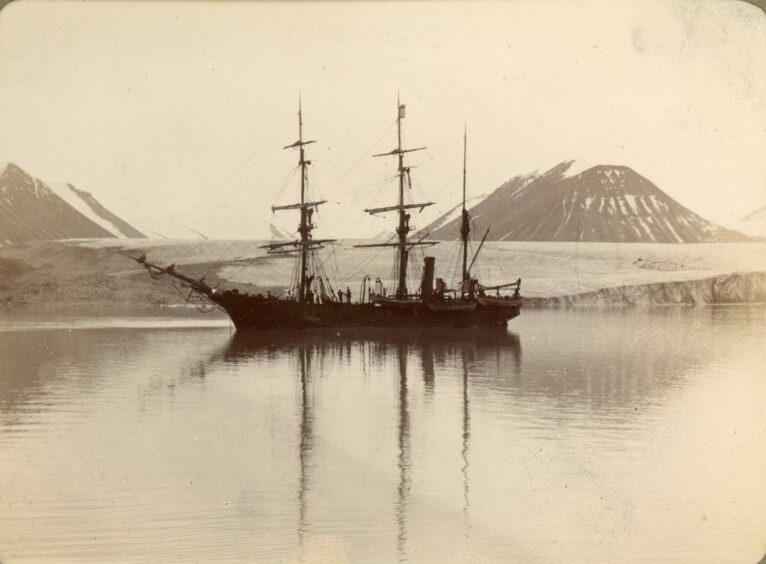

Over exploitation of bowhead whales around Svalbard saw whaling fleets move to the Davis Strait then up into Baffin Bay.

Dundee’s presence in the whaling industry began in 1753 starting with the ship ‘Dundee’.

But by the mid-19th century whaling was in decline with only Scottish ports –particularly Dundee – persisting until the start of the First World War.

While several hundred ships were lost in the treacherous waters, Nova Zembla itself is significant because the wreck is the first identified British Arctic whaling wreck in the High Arctic in Canada.

Dundee captain ‘ignored by history’

Matt is also fascinated by the story of Captain John Cooney who, despite being highly experienced, sank the Nova Zembla on his first command.

He then went on to be involved in a survival operation that could be compared with Shackleton’s famous escapades in the Antarctic.

Yet, unlike Shackelton, Cooney is “almost ignored by history”.

“He was very unlucky,” said Matt.

“He sank Nova Zembla on his first command, even though he was very experienced.

“Then the owners bought the Vega which was already very famous. It was the first ship ever to do the North East Passage under a Swedish expedition.

“It was Nova Zembla’s sister ship. They were built side by side in Bremerhaven in Germany.

“He sinks the Vega. But he himself and the 40 crew make about a 300 nautical mile open water journey in the whale boats to a community on the west coast of Greenland to safety, which is quite a feat of endurance.

“Shackleton is famous for his voyage from Elephant Island to South Georgia with five people in one of these whaling boats essentially.

“That was 800 nautical miles. Everyone celebrates this as huge feat of endurance and it’s amazing.

“Cooney very much did a similar thing. More men. Less distance. But it’s largely unknown.

“Next they give Cooney command of the Windward.

“It’s another very famous ship originally from Peterhead with two famous expeditions under its name before being sold back to Dundee to be a whaler. Cooney gets command in 1904.

“He sails it for a few years and in 1907, he wrecks the Windward off north west Greenland!”

Working people

Matt says he doesn’t believe history gives the whalers the recognition they deserve, probably because of their trade and the way society now views commercial whaling.

But another reason, he says, is because they were “just working people”.

“They weren’t explorers which were usually well off or well backed or Royal Navy,” he said.

“They weren’t “gentlemen”.

“Explorers got recognition for doing these things in the Arctic and Antarctic, but the whalers were kind of doing them every year!

“Sometimes these explorers’ expedition would push much further into dangerous territory and folk would usually die.

“Whereas the whalers were a little more sensible most of the time.

“But they were still exploring and charting most of the coast.

“You can go down Baffin Island on a modern chart and look at the English names for places, and a lot of them, if they are not named by the Royal Navy they are to do with whalers.”

Dundee connections

One Dundee connection came to light when Matt was looking through the British Library newspaper archive and doing a place name search for the youth group project he’s involved with.

“There’s a community called Arctic Bay up there,” he said.

“I thought – and everyone I know living up that way thought – it was called Arctic Bay because it was a bay in the Arctic. But it’s actually named after the ship the Arctic that sailed from Dundee. There’s some mad little titbits of history in there!”

What else can be learned?

From an historical point of view Matt doesn’t think there’s much more to be learned from the Nova Zembla wreck.

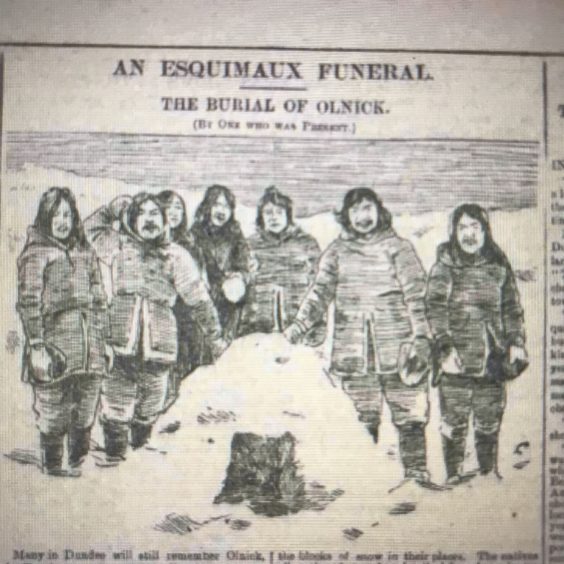

But he continues to be fascinated by the link to Olnick – the Inuit who asked to travel back to Dundee with the whalers in 1878 and became a minor celebrity.

He was known for salvaging wrecks around Baffin and re-using materials.

It was reported he salvaged the wreck of the Ravenscraig out of Kirkcaldy.

But when he died in 1900, his son in law took over and the group moved south. That explains why when Nova Zembla wrecks two years later nobody salvaged it.

Matt is pretty certain he knows where the site of Olnick’s settlement is.

Given that Olnick almost certainly salvaged the Dundee-built Eagle, he’d love to find the settlement and find evidence of how the ship was re-used in the community.

“That would be fascinating and we could learn a lot,” he added.

Conversation